You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

MHB Proof by induction? No Idea what I should do :(

AI Thread Summary

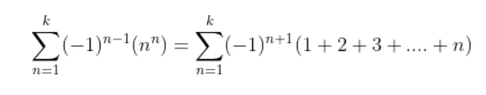

The discussion focuses on proving a mathematical statement by induction, specifically the equation involving the sum of squares with alternating signs. The initial attempts to establish the general rule were corrected, emphasizing the need to simplify the right side using the known formula for the sum of the first n integers. The correct equation to prove is presented as the sum of squares equating to a specific expression involving k. The conversation concludes with guidance on how to manipulate the equation to complete the proof, stressing the importance of verifying the base case and the inductive step.

Physics news on Phys.org

Opalg

Gold Member

MHB

- 2,778

- 13

You have the correct formula, except that $n^n$ should be $n^2$. I think your next step should be to simplify the right side of the formula by using the formula (which you probably know?) for the sum of the numbers $1$ to $n$. After that, you should be able to apply the method of induction.FriendlyCashew said:find the general rule and prove by induction

1 = 1

1 - 4 = -(1 + 2)

1 - 4 + 9 = 1 + 2 + 3

1 - 4 + 9 -16 = -(1 + 2 + 3 + 4)

I created this so far, but don't know if I am even going the correct direction

View attachment 10459

- 2,020

- 843

Actually, I think what you want isFriendlyCashew said:find the general rule and prove by induction

1 = 1

1 - 4 = -(1 + 2)

1 - 4 + 9 = 1 + 2 + 3

1 - 4 + 9 -16 = -(1 + 2 + 3 + 4)

I created this so far, but don't know if I am even going the correct direction

View attachment 10459

[math]\sum_{n = 1}^k (-1)^{n - 1} n^2 = (-1)^{k + 1} \sum_{n = 1}^k n[/math]

Does this work for some value of k? (Sure, try k = 1.) So if it works for k, does it work for k + 1?

-Dan

FriendlyCashew

- 2

- 0

Is this correct?

Opalg

Gold Member

MHB

- 2,778

- 13

The equation that you are trying to prove by induction is $$\sum_{n = 1}^k (-1)^{n - 1} n^2 = (-1)^{k + 1} \sum_{n = 1}^k n$$. Your first attempt at this was wrong, and so was mine (sorry about that). But topsquark got it right. The next step is to use the fact that $$ \sum_{n = 1}^k n = \frac12k(k+1)$$. So you want to prove that $$\sum_{n = 1}^k (-1)^{n - 1} n^2 = \frac12(-1)^{k + 1}k(k+1)$$. That equation is true when $k=1$ because both sides are then equal to $1$.FriendlyCashew said:find the general rule and prove by induction

1 = 1

1 - 4 = -(1 + 2)

1 - 4 + 9 = 1 + 2 + 3

1 - 4 + 9 -16 = -(1 + 2 + 3 + 4)

I created this so far, but don't know if I am even going the correct direction

View attachment 10459

Now suppose that the equation is true for $k$. You want to show that it is also true for $k+1$, namely that $$\sum_{n = 1}^{k+1} (-1)^{n - 1} n^2 = \frac12(-1)^{k + 2}(k+1)(k+2)$$. On the left side of the equation, that differs from the previous equation just by the addition of one extra term $(-1)^k(k+1)^2$. So starting with the known equation $$ \sum_{n = 1}^k (-1)^{n - 1} n^2 = \frac12(-1)^{k + 1}k(k+1)$$, add $(-1)^k(k+1)^2$ to each side to get $$\sum_{n = 1}^{k+1} (-1)^{n - 1} n^2 = \frac12(-1)^{k + 1}k(k+1) + (-1)^k(k+1)^2$$.

Now can you simplify the right side of that equation to complete the proof?

I'm taking a look at intuitionistic propositional logic (IPL). Basically it exclude Double Negation Elimination (DNE) from the set of axiom schemas replacing it with Ex falso quodlibet: ⊥ → p for any proposition p (including both atomic and composite propositions).

In IPL, for instance, the Law of Excluded Middle (LEM) p ∨ ¬p is no longer a theorem.

My question: aside from the logic formal perspective, is IPL supposed to model/address some specific "kind of world" ?

Thanks.

I was reading a Bachelor thesis on Peano Arithmetic (PA). PA has the following axioms (not including the induction schema):

$$\begin{align}

& (A1) ~~~~ \forall x \neg (x + 1 = 0) \nonumber \\

& (A2) ~~~~ \forall xy (x + 1 =y + 1 \to x = y) \nonumber \\

& (A3) ~~~~ \forall x (x + 0 = x) \nonumber \\

& (A4) ~~~~ \forall xy (x + (y +1) = (x + y ) + 1) \nonumber \\

& (A5) ~~~~ \forall x (x \cdot 0 = 0) \nonumber \\

& (A6) ~~~~ \forall xy (x \cdot (y + 1) = (x \cdot y) + x) \nonumber...

Similar threads

- Replies

- 3

- Views

- 2K

- Replies

- 5

- Views

- 4K

- Replies

- 13

- Views

- 2K

- Replies

- 4

- Views

- 2K

- Replies

- 4

- Views

- 4K

- Replies

- 6

- Views

- 2K

- Replies

- 7

- Views

- 2K

- Replies

- 1

- Views

- 1K

- Replies

- 6

- Views

- 2K

- Replies

- 13

- Views

- 2K

Hot Threads

-

B A Little Probability Puzzle

- Started by bob012345

- Replies: 20

- Set Theory, Logic, Probability, Statistics

-

I Need help solving this Existence Algorithm for truth

- Started by ollieha

- Replies: 1

- Set Theory, Logic, Probability, Statistics

-

I Help me understand skewness in QQ-plots please

- Started by bremenfallturm

- Replies: 1

- Set Theory, Logic, Probability, Statistics

-

A Distribution of Range of Samples taken from N(0,1)

- Started by uart

- Replies: 1

- Set Theory, Logic, Probability, Statistics

Recent Insights

-

Insights Thinking Outside The Box Versus Knowing What’s In The Box

- Started by Greg Bernhardt

- Replies: 3

- Other Physics Topics

-

Insights Why Entangled Photon-Polarization Qubits Violate Bell’s Inequality

- Started by Greg Bernhardt

- Replies: 28

- Quantum Interpretations and Foundations

-

Insights Quantum Entanglement is a Kinematic Fact, not a Dynamical Effect

- Started by Greg Bernhardt

- Replies: 11

- Quantum Physics

-

Insights What Exactly is Dirac’s Delta Function? - Insight

- Started by Greg Bernhardt

- Replies: 3

- General Math

-

Insights Relativator (Circular Slide-Rule): Simulated with Desmos - Insight

- Started by Greg Bernhardt

- Replies: 1

- Special and General Relativity

-

Insights Fixing Things Which Can Go Wrong With Complex Numbers

- Started by PAllen

- Replies: 7

- General Math