ThorX89

- 13

- 0

Hi.

I'm curious, how would a charged particle, let's say an electron, move in a simple uniform electric field?

My first guess would be that it would follow Newton's second law of motion and move with a constant acceleration:

$ \dot{x}=\frac{Eq}{m} $

where E is the fields intensity, q the charge, and m it's mass.

However, an accelerated charge should generate electromagnetic waves.

These have energy and so the motion wouldn't accelerate as fast.

I found that the energy radiated by these should be equal to:

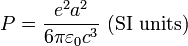

(Larmor formula) for norelativistic speeds.

So I would assume that the work done by the electric field on the charge in a fraction of time:

$ P_{el} = q\cdot E \cdot \dot{x} $

would be used to a) increase the kinetic energy of the particle b) used for the radiation energy:

\[P_{el}=\frac{d}{dt}(\frac{1}{2}m\dot{x}^2) + P_{rad}\]

That leads to the differential equation:

$ A \cdot \dot{x} = m \cdot \dot{x} \cdot \ddot{x} + B \cdot \ddot{x}^2 $

where

$ A=Eq ; B=\frac{{q^2}}{{6\cdot\pi\eps_0\ c^3}} $

(just to make it look simpler).

I have now idea how to solve this.

Do you think my reasoning is right? If so, can anybody find a solution?

How is the motion of a charged particle in a uniform electric field truly described?

I'd think this is quite a simple question, but I couldn't find any simple answer to it on the Internet.

I appreciate any help.

I'm curious, how would a charged particle, let's say an electron, move in a simple uniform electric field?

My first guess would be that it would follow Newton's second law of motion and move with a constant acceleration:

$ \dot{x}=\frac{Eq}{m} $

where E is the fields intensity, q the charge, and m it's mass.

However, an accelerated charge should generate electromagnetic waves.

These have energy and so the motion wouldn't accelerate as fast.

I found that the energy radiated by these should be equal to:

(Larmor formula) for norelativistic speeds.

So I would assume that the work done by the electric field on the charge in a fraction of time:

$ P_{el} = q\cdot E \cdot \dot{x} $

would be used to a) increase the kinetic energy of the particle b) used for the radiation energy:

\[P_{el}=\frac{d}{dt}(\frac{1}{2}m\dot{x}^2) + P_{rad}\]

That leads to the differential equation:

$ A \cdot \dot{x} = m \cdot \dot{x} \cdot \ddot{x} + B \cdot \ddot{x}^2 $

where

$ A=Eq ; B=\frac{{q^2}}{{6\cdot\pi\eps_0\ c^3}} $

(just to make it look simpler).

I have now idea how to solve this.

Do you think my reasoning is right? If so, can anybody find a solution?

How is the motion of a charged particle in a uniform electric field truly described?

I'd think this is quite a simple question, but I couldn't find any simple answer to it on the Internet.

I appreciate any help.