juvan

- 13

- 0

Hello everyone,

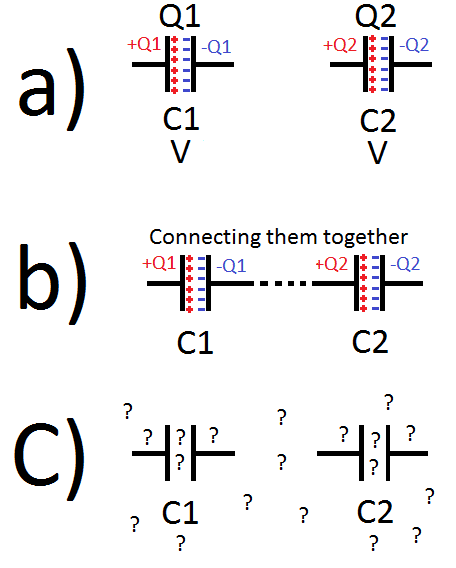

I have drawn a picture of my confusion, I think it says it all:

Now to add some text: so we charge two capacitors C1 and C2 to a voltage V. Now we have two charged capacitors. We now connect -Q1 to +Q2 and nothing else (the other two legs are floating). From my basic understanding of physics opposite charges attract so in our case I feel as though there should be some charge movement, even though we don't have a closed circuit (basic electronics) we still have opposite charges connected by a conductor (basic physics).

I am asking for an overall explanation of the scenario. What I would like most is not an explanation with equations but with simple words and the physical goings on.

Thank you.

I have drawn a picture of my confusion, I think it says it all:

Now to add some text: so we charge two capacitors C1 and C2 to a voltage V. Now we have two charged capacitors. We now connect -Q1 to +Q2 and nothing else (the other two legs are floating). From my basic understanding of physics opposite charges attract so in our case I feel as though there should be some charge movement, even though we don't have a closed circuit (basic electronics) we still have opposite charges connected by a conductor (basic physics).

I am asking for an overall explanation of the scenario. What I would like most is not an explanation with equations but with simple words and the physical goings on.

Thank you.