Adrian Simons

- 10

- 4

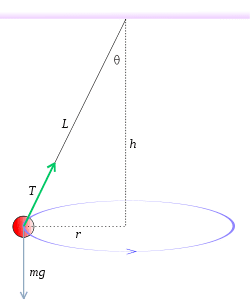

Consider a conical pendulum like that shown in the figure. A ball of mass, m, attached to a string of length, L, is rotating in a circle of radius, r, with angular velocity, ω. The faster we spin the ball (i.e., the greater the ω), the greater the angle, θ, will be, and thus, the smaller the height, h will be.

But now imagine that instead of suspending the ball from a string, we use something like a rubber band that can stretch. Then the faster and faster we spin the ball, the more the rubber band stretches. So we expect L will increase, θ will increase, and h will decrease.

Now let's take a set of different rubber bands. The original lengths of all the rubber bands, with the mass, m, suspended from them vertically, are all identical. However, with a given amount of force, each rubber band stretches a different amount. In other words, say we can model a rubber band as if it were a spring. Then different rubber bands have different spring constants. But remember that they all have the same length, L, when the mass, m, is suspended vertically, before anything starts to spin.

So why is it that regardless of which rubber band you use, as long as you keep ω the same, h remains the same? I mean I worked out the equations and found this to be true. However, I found it to be an unexpected result. Can anybody give me some intuitive insight as to why this should be so?

By the way, this is totally independent of exactly what the nature of the force is that the rubber band exerts, as long as the force is a function of the amount the rubber band stretches.

But now imagine that instead of suspending the ball from a string, we use something like a rubber band that can stretch. Then the faster and faster we spin the ball, the more the rubber band stretches. So we expect L will increase, θ will increase, and h will decrease.

Now let's take a set of different rubber bands. The original lengths of all the rubber bands, with the mass, m, suspended from them vertically, are all identical. However, with a given amount of force, each rubber band stretches a different amount. In other words, say we can model a rubber band as if it were a spring. Then different rubber bands have different spring constants. But remember that they all have the same length, L, when the mass, m, is suspended vertically, before anything starts to spin.

So why is it that regardless of which rubber band you use, as long as you keep ω the same, h remains the same? I mean I worked out the equations and found this to be true. However, I found it to be an unexpected result. Can anybody give me some intuitive insight as to why this should be so?

By the way, this is totally independent of exactly what the nature of the force is that the rubber band exerts, as long as the force is a function of the amount the rubber band stretches.