- 3,481

- 1,292

Hydrostatic pressure is static pressure.

The discussion revolves around the assumptions and implications of incompressible flow in fluid mechanics, particularly in relation to pressure and density. Participants explore the validity of using the incompressible fluid model, the relationship between pressure and density, and the application of Bernoulli's equation in varying geometries of flow, with a focus on theoretical and conceptual aspects.

Participants express multiple competing views regarding the assumptions of incompressibility, the validity of certain equations, and the implications of pressure and density relationships in fluid mechanics. The discussion remains unresolved, with no consensus on the correctness of the various claims made.

Limitations include the dependence on specific definitions of incompressibility and compressibility, as well as unresolved mathematical steps regarding the integration of pressure and density relations. The applicability of Bernoulli's equation under different flow conditions is also a point of contention.

Yes it is.boneh3ad said:Hydrostatic pressure is static pressure.

Malverin said:Yes it is.

In the equation it is considered separately (and it should be, because atmospheric and hydrostatic pressure are not the same thing)

so to be correct we have to consider it separately.

And to generalize all this

When fluid does not move the total pressure is static pressure (atmospheric + hydrostatic)

Niles said:I am confused, does this mean you understand what the solution to the problem is?

Malverin said:There is no problem if you use total pressure in the 'speed of sound' formula

Niles said:But it is not total pressure in that formula, it is static. I know that because this is the pressure that eventually becomes the ∇p-term in the NS-equations

Malverin said:Show us some reference about that then.

I don't pretend i understand that better than you.

I just can not understand the reason for your assumptions.

If you can show us some reference it will be easier to understand where the problem is.

Niles said:From my post #19: "Please take a look at this paper, on the second page equation (5). There they state that p=c_s^2\rho".

In eq. (25) they use this very same p in the NS-equations.

LB models

can be used in a low Mach-number regime to simulate

incompressible flows. In that case, the pressure p of the

fluid is related to the particle density through the equation of state for an ideal gas:

Malverin said:So it is written for ideal gas

Nothing said, about gravity

When there is no gravity => there is no hydrostatic pressure

it is written this is valid for 'low Mach number'

That means they consider dynamic pressure negligible , or they mean something else?

It is not clear to me.

Niles said:Low Mach number just means low velocity, so basically fluid can be approximated as incompressible. But Bernoulli's eqs. is still valid!

Malverin said:Any gas is compressible even at low speed.

So I don't think this is sufficient condition for incompressibility.

Niles said:So you agree with me, there really is an inconsistency somewhere, right?

Malverin said:atmospheric and hydrostatic pressure are not the same thing

Malverin said:When fluid does not move the total pressure is static pressure (atmospheric + hydrostatic)

Malverin said:So it is written for ideal gas

Nothing said, about gravity

When there is no gravity => there is no hydrostatic pressure

Malverin said:it is written this is valid for 'low Mach number'

That means they consider dynamic pressure negligible , or they mean something else?

It is not clear to me.

Malverin said:Any gas is compressible even at low speed.

So I don't think this is sufficient condition for incompressibility.

boneh3ad said:Yikes, so much nonsense all in one thread...

No I am not saying that. I do not have that particular book from White and I don't have any other texts containing that relationship that I can recall (or find by searching briefly through my library). What I will say is that generally,

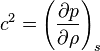

c_s = \left(\dfrac{\partial p}{\partial \rho}\right)_s

where the subscript ##s## denotes the derivative is taken at constant entropy. The only way you arrive at your equation is by assuming that this relation can be expressed here as an ordinary derivative, separating the two sides and then assuming the sound speed is constant so that it doesn't get affected by the integral, then assuming the constant of integration is zero. I do not know Frank White's assumptions made when deriving the relationship you cited and without seeing what he did, I can't really comment on why it doesn't work for your situation.

What I can say is that based on the latest paper you cited, they are using this equation as an equation of state relating the thermodynamic variables ##p## and ##\rho##. The speed of sound is determined elsewhere and is treated as a known quantity.

Be careful here again. There may not be gravity used in a given problem, but the static pressure of a stagnant fluid, for example, is still likely a result of hydrostatic pressure. Gravity is often simply not included because its contribution to the change in pressure in a given situation is negligible. Either way, that is irrelevant to the discussion since the speed of sound relationship depends on static pressure regardless of the "source" of that static pressure, or more correctly, it depends on the rate of change of the pressure with respect to the density at constant entropy.

That is absolutely not what low Mach number implies. At sea level in air, you can be moving at a "low Mach number" (typically meaning M < 0.3) and still be moving at over 100 m/s (224 mph)! There will certainly be some non-negligible dynamic pressure there. What it implies is that for a low enough Mach number, the flow can be considered incompressible. If you need convincing of this, I worked out the math in this thread not too long ago showing why the Mach number is a good indicator of compressibility.

Also remember that this incompressible assumption is, as AlephZero has stressed, an approximation. No fluid is truly incompressible.

Also, ladies and gents, keep in mind that "incompressible" does not mean constant density. It means that the material derivative of density is zero, or alternatively that the divergence of the velocity field is zero (from the continuity equation). You can certainly still have variable density in an incompressible flow provided that this condition is met.

This depends on how you define total pressure. Sometimes total pressure includes the ##\rho g z## term factoring in potential energy, so be careful.

Based on the typical definition of atmospheric pressure, yes, it is a form of hydrostatic pressure. It simply varies with height, and since you have two fluids stacked on top of one another, you have to include the weight of one in the hydrostatic pressure of the other. That doesn't change the fact that atmospheric pressure is the hydrostatic pressure from the air.

Of course, the important thing is that either way, total pressure is not useful as a thermodynamic property, as it is frame-dependent. For that reason, most equations, such as the Navier-Stokes equatiuons and the equation for speed of sound discussed here, use static pressure, which is frame-independent, confirming what Niles has been saying.

Malverin said:Incompresible means constant volume.

So if the volume is constant and the mass is constant too, there can not be variable density.

Malverin said:If the speed of sound is determined only by static pressure, according to Bernoulli principal, there will be a huge difference in sound speed for stationary and moving (with 100 m/s as you say) fluid, because when fluid moves, static pressure will drop significantly, especially in water.

Malverin said:They have very different density .

And much more different hydrostatic heights.

So you have to calculate them separately.

Malverin said:Speed is frame dependent too.

So 'low Mach number' is a very relative term too

boneh3ad said:Also, ladies and gents, keep in mind that "incompressible" does not mean constant density. It means that the material derivative of density is zero, or alternatively that the divergence of the velocity field is zero (from the continuity equation). You can certainly still have variable density in an incompressible flow provided that this condition is met.

Also remember that this incompressible assumption is, as AlephZero has stressed, an approximation. No fluid is truly incompressible.

boneh3ad said:In continuum mechanics that is only true if you specifically mean that a given fluid element remains at constant volume. To illustrate, the continuity equation is

\dfrac{D\rho}{Dt} + \rho(\nabla \cdot \vec{V}) = 0.

For an incompressible flow, we say that ##\frac{D\rho}{Dt} = 0##, which is therefore the same as requiring that ##\nabla \cdot \vec{V}=0##, which says that there is no dilatation of a fluid element. That completely allows for variable density under certain conditions. For example, if I place a probe on the hood of my car that somehow measures density and then drove around indoors at a constant speed, the probe very well could (and would) measure density fluctuations despite the flow being "incompressible".

Liquids and gases cannot bear steady uniaxial or biaxial compression, they will deform promptly and permanently and will not offer any permanent reaction force. However they can bear isotropic compression, and may be compressed in other ways momentarily, for instance in a sound wave.

Tightening a corset applies biaxial compression to the waist.

Every ordinary material will contract in volume when put under isotropic compression, contract in cross-section area when put under uniform biaxial compression, and contract in length when put into uniaxial compression.

Malverin said:You are speaking about a constant mass flow.

Any incompressible fluid has constant mass flow, but constant mass flow doesn't ensure incompressibility.

Malverin said:Any compression is change in volume. So if you have a change in volume, there is a compression.

boneh3ad said:That's not true. You can very certainly have unsteady, incompressible flows. It's true that constant mass flow does not necessarily imply incompressibility, but incompressibility does not imply constant mass flow either. The flow field around a swinging pendulum, for example, is time-varying, including the mass flow around the pendulum, and it is most certainly incompressible.

You simply have to be careful about what you are saying is changing. In continuum mechanics, the concept of incompressibility says that a given fluid element does not change volume. This is, of course, assuming that the given fluid element is not gaining mass for any reason. A stronger statement is that a given element's density does not change. That still allows for a given fluid element to be highly deformed under the action of the stress tensor but remain at constant volume (or density) and it allows for for many fluid elements of varying volume (or density) to flow by a fixed measurement point.