Let's go through the logic of polar coordinates to summarize what has been achieved nicely above:

It's a simple example for curvilinear orthogonal coordinates. You start from a cartesian basis ##\vec{e}_1## and ##\vec{e}_2##. Then you define polar coordinates ##(r,\theta)## with ##r \in \mathbb{R}_{>0}## and ##\theta \in ]-\pi,\pi]## (of course you can define the angle to be in any semi-open interval of length ##2 \pi##) as

$$\vec{r}=x \vec{e}_1+ y \vec{e}_2=r \cos \theta \vec{e}_1 + r \sin \theta \vec{e}_2.$$

Then it's also convenient to define, at each point, a basis system given by the tangent vectors of the coordinate lines, i.e., the lines given by holding one of the two polar coordinates constant:

$$\vec{b}_r=\partial_r \vec{r}=\cos \theta \vec{e}_1 + \sin \theta \vec{e}_2, \quad \vec{b}_{\theta}=\partial_{\theta} \vec{r}=-r \sin \theta \vec{e}_1 + r \cos \theta \vec{e}_2.$$

It's easy to see that

$$\vec{b}_r \cdot \vec{b}_{\theta}=0,$$

i.e., that the two tangent vectors on the coordinate lines at any point are orthogonal to each other. In this case, usually one chooses the basis for the curvilinear coordinates as normalized. Now ##\vec{b}_r^2=1## and ##\vec{b}_{\theta}^2=r^2##. Thus we define

$$\vec{e}_r=\vec{b}_r = \cos \theta \vec{e}_1 + \sin \theta \vec{e}_2, \quad \vec{e}_{\theta}=\frac{1}{r} \vec{b}_{\theta} = -\sin \theta \vec{e}_1 + \cos \theta \vec{e}_2.$$

Now you have at any point a orthonormal basis system since

$$\vec{e}_{r}^2=\vec{e}_{\theta}^2=1, \quad \vec{e}_r \cdot \vec{e}_{\theta}=0.$$

Now as with any basis you can define vector components with respect to this "curvilinear bases". In your case this was done for the velocity vector. To that end just use the original Cartesian coordinates first and then express the resulting vectors in terms of the new basis vectors:

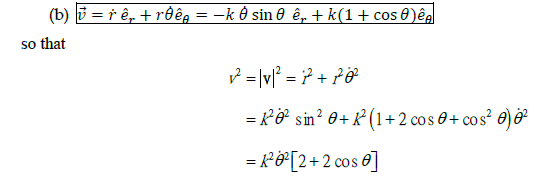

$$\vec{v}=\dot{\vec{r}}=\mathrm{d}_t (r \cos \theta \vec{e}_1 + r \sin \theta \vec{e}_2) = \dot{r} \vec{e}_r + r \dot{\theta} \vec{e}_{\theta}.$$

Thus you have the components

$$v_r=\dot{r}, \quad v_{\theta}=r \dot{\theta}.$$

Now, since these are components with respect to an orthronormal basis, you get

$$\vec{v}^2=(v_r \vec{e}_r + v_{\theta} \vec{e}_{\theta})^2=v_r^2 \vec{e}_r^2 + v_{\theta}^2 \vec{e}_{\theta}^2 + 2 v_r v_{\theta} \vec{e}_r \cdot \vec{e}_{\theta}=v_r^2 + v_{\theta}^2 = \dot{r}^2 + r^2 \dot{\theta}^2.$$