Sonderval

- 234

- 11

I was always a bit puzzled by the Heisenberg picture (not mathematically, I'm fine with that, but conceptually) - if a "state" describes a system, how can it not be time-dependent, if the system changes?

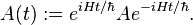

I just found an alternative way of looking at it which seems to make sense to me, but I'm not sure whether it really is correct. Here is the operator evolution equation (stolen from Wikipedia).

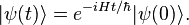

This will always be applied to some state |ψ> (so that the time evolution of the Schrödinger picture

is recovered).

|ψ(0)> is the initial state of the system (and is the same in both pictures). So would it be acceptable to say that in the Heisenberg picture, I use the operators to contain the time evolution of the system and always apply them to the initial state? So |ψ> actually never enters the equation as a state at any time except at t=0 and acts only as initial conditions.

In other words: In the Schrödinger picture we have some initial condition (or initial state) and look at how this state evolves. In the Heisenberg picture, we plug the mathematics of the evolution into the operators and can then apply them always to the initial conditions. So it is not so much that the state does not change in time, but that we never have to look at the state at any time except t=0.

I just found an alternative way of looking at it which seems to make sense to me, but I'm not sure whether it really is correct. Here is the operator evolution equation (stolen from Wikipedia).

This will always be applied to some state |ψ> (so that the time evolution of the Schrödinger picture

is recovered).

|ψ(0)> is the initial state of the system (and is the same in both pictures). So would it be acceptable to say that in the Heisenberg picture, I use the operators to contain the time evolution of the system and always apply them to the initial state? So |ψ> actually never enters the equation as a state at any time except at t=0 and acts only as initial conditions.

In other words: In the Schrödinger picture we have some initial condition (or initial state) and look at how this state evolves. In the Heisenberg picture, we plug the mathematics of the evolution into the operators and can then apply them always to the initial conditions. So it is not so much that the state does not change in time, but that we never have to look at the state at any time except t=0.