Darkmisc

- 222

- 31

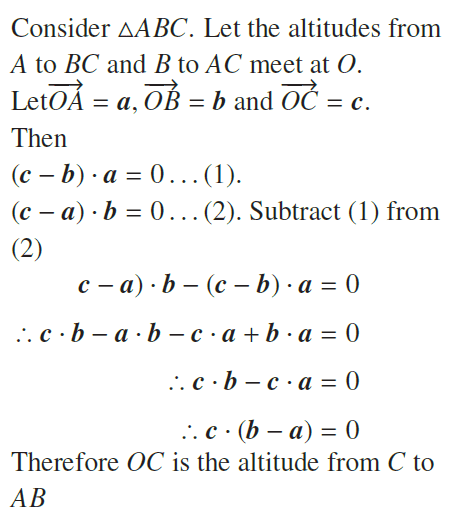

- Homework Statement

- Prove that the altitudes of a triangle are concurrent. That is, they meet at a point.

- Relevant Equations

- Dot product of perpendicular vectors = 0

Hi everyone

I have the solutions to this problem, but I'm not sure I fully understand them.

Is the idea behind the proof that all of the following can only be true if the altitudes meet at O?

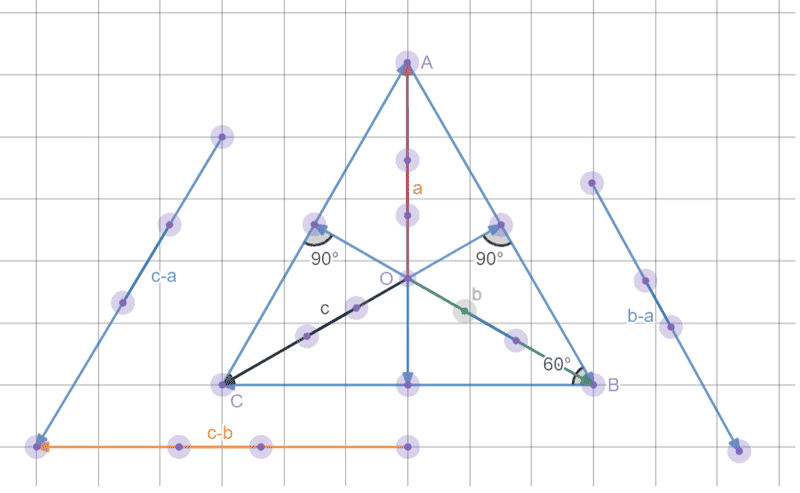

1. c-b is perpendicular to a

2. c-a is perpendicular to b

3. b-a is perpendicular to c.

That is, if they didn't meet at O, the component vectors of c-b would not cancel so that the resultant vector is perpendicular to a (and the same holds for (c-a)*b and (b-a)*c).Thanks

NB. a = OA, b = OB, c = OC. I used a segment to make labels and I'm stuck with the dots at the end of the segments.

I have the solutions to this problem, but I'm not sure I fully understand them.

Is the idea behind the proof that all of the following can only be true if the altitudes meet at O?

1. c-b is perpendicular to a

2. c-a is perpendicular to b

3. b-a is perpendicular to c.

That is, if they didn't meet at O, the component vectors of c-b would not cancel so that the resultant vector is perpendicular to a (and the same holds for (c-a)*b and (b-a)*c).Thanks

NB. a = OA, b = OB, c = OC. I used a segment to make labels and I'm stuck with the dots at the end of the segments.