- #1

LCSphysicist

- 645

- 161

- Homework Statement

- How can i know that the orbit represented by the equation is symmetric with respect to two points?

- Relevant Equations

- I will post an image below so it doesn't get confused

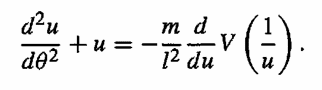

How can i know the resulting orbit of

is symmetric about two turning points?

is symmetric about two turning points?

Where m, l is constant.

V is function of r

u = 1/r

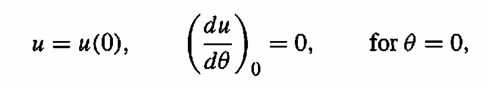

and

It is in polar coordinates.

We could show that varying theta from 0 to -θ will be the same if we vary 0 to Θ, but i don't know where to start

Where m, l is constant.

V is function of r

u = 1/r

and

It is in polar coordinates.

We could show that varying theta from 0 to -θ will be the same if we vary 0 to Θ, but i don't know where to start