Math Amateur

Gold Member

MHB

- 3,920

- 48

I am reading Loring W.Tu's book: "An Introduction to Manifolds" (Second Edition) ...

I need help in order to fully understand Tu's section on the wedge product (Section 3.7 ... ) ... ...

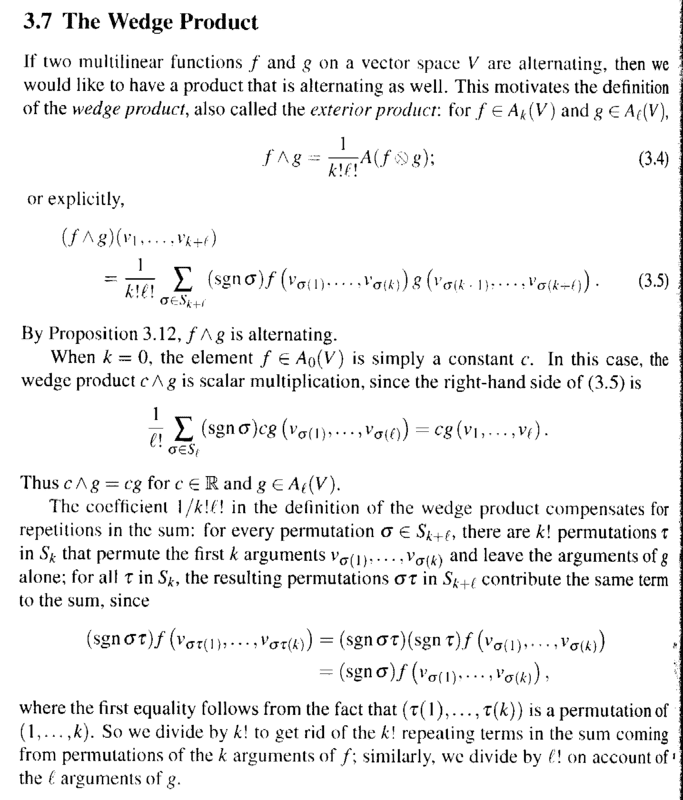

The start of Section 3.7 reads as follows:

In the above text from Tu we read the following:

" ... ... for every permutation ##\sigma \in S_{ k + l }##, there are ##k!## permutations ##\tau## in ##S_k## that permute the first ##k## arguments ##v_{ \sigma (1) }, \cdot \cdot \cdot , v_{ \sigma (k) }## and leave the arguments of ##g## alone; for all ##\tau## in ##S_k##, the resulting permutations ##\sigma \tau## in ##S_{ k + l }## contribute the same term to the sum, ... ... "Since I did not completely understand the above quoted statement I developed an example with ##f \in A_2 (V)## and ##g \in A_3 (V)## ... ... so we have##f \wedge g ( v_1 \cdot \cdot \cdot v_5) ##

## = \frac{1}{2!} \frac{1}{3!} \sum_{ \sigma \in S_5 } f ( v_{ \sigma (1) }, v_{ \sigma (2) } ) g( v_{ \sigma (3) }, v_{ \sigma (4) }, v_{ \sigma (5) } )##Now ... translating Tu's quoted statement above into the terms of the example we have ... ...

" ... for every permutation ##\sigma \in S_{ 2 + 3 }## there are ##2! = 2## permutations ##\tau## in ##S_2## that permute the first ##2## arguments ##v_{ \sigma (1) }, v_{ \sigma (2) }## and leave the arguments of ##g## alone ... ... "

Now, following the above quoted text ... consider a specific permutation ##\sigma## ... say## \sigma_1 = \begin{bmatrix} 1 & 2 & 3 & 4 & 5 \\ 2 & 3 & 4 & 5 & 1 \end{bmatrix}##Now there are ##2!= 2## permutations ##\tau## in ##S_2## that permute the first ##k = 2## arguments ##( v_{ \sigma (1) }, v_{ \sigma (2) } ) = ( v_2, v_3 )## ...

[Note ... one of the ##k!## permutations is essentially ##\sigma_1## itself ... ]

These permutations may be represented by (is this correct?)

... in ##S_2## ...

##\tau_1 = \begin{bmatrix} 2 & 3 \\ 2 & 3 \end{bmatrix}##

##\tau_2 = \begin{bmatrix} 2 & 3 \\ 3 & 2 \end{bmatrix}##and in ##S_{ 2 + 3 }## ...## \tau_1 = \begin{bmatrix} 2 & 3 & 4 & 5 & 1 \\ 2 & 3 & 4 & 5 & 1 \end{bmatrix}##

## \tau_2 = \begin{bmatrix} 2 & 3 & 4 & 5 & 1 \\ 3 & 2 & 4 & 5 & 1 \end{bmatrix}##Now the resulting permutations ##\sigma \tau## are supposed to contribute the same term to the sum ...... ... ##\sigma_1 \tau_1 = \begin{bmatrix} 1 & 2 & 3 & 4 & 5 \\ 2 & 3 & 4 & 5 & 1 \end{bmatrix} \begin{bmatrix} 2 & 3 & 4 & 5 & 1 \\ 2 & 3 & 4 & 5 & 1 \end{bmatrix}##

## = \begin{bmatrix} 1 & 2 & 3 & 4 & 5 \\ 2 & 3 & 4 & 5 & 1 \end{bmatrix}##and## \sigma_1 \tau_2 = \begin{bmatrix} 1 & 2 & 3 & 4 & 5 \\ 2 & 3 & 4 & 5 & 1 \end{bmatrix} \begin{bmatrix} 2 & 3 & 4 & 5 & 1 \\ 3 & 2 & 4 & 5 & 1 \end{bmatrix}#### = \begin{bmatrix} 1 & 2 & 3 & 4 & 5 \\ 2 & 4 & 3 & 5 & 1 \end{bmatrix} ##

Now the two permutations are not identical ... but ... maybe the difference is accounted for in the ##( \text{ sgn } ) ## function somehow ... but how ... ?

Can someone please clarify the above ...

... ... could someone also confirm that the above analysis is basically correct ... ?

Peter

I need help in order to fully understand Tu's section on the wedge product (Section 3.7 ... ) ... ...

The start of Section 3.7 reads as follows:

In the above text from Tu we read the following:

" ... ... for every permutation ##\sigma \in S_{ k + l }##, there are ##k!## permutations ##\tau## in ##S_k## that permute the first ##k## arguments ##v_{ \sigma (1) }, \cdot \cdot \cdot , v_{ \sigma (k) }## and leave the arguments of ##g## alone; for all ##\tau## in ##S_k##, the resulting permutations ##\sigma \tau## in ##S_{ k + l }## contribute the same term to the sum, ... ... "Since I did not completely understand the above quoted statement I developed an example with ##f \in A_2 (V)## and ##g \in A_3 (V)## ... ... so we have##f \wedge g ( v_1 \cdot \cdot \cdot v_5) ##

## = \frac{1}{2!} \frac{1}{3!} \sum_{ \sigma \in S_5 } f ( v_{ \sigma (1) }, v_{ \sigma (2) } ) g( v_{ \sigma (3) }, v_{ \sigma (4) }, v_{ \sigma (5) } )##Now ... translating Tu's quoted statement above into the terms of the example we have ... ...

" ... for every permutation ##\sigma \in S_{ 2 + 3 }## there are ##2! = 2## permutations ##\tau## in ##S_2## that permute the first ##2## arguments ##v_{ \sigma (1) }, v_{ \sigma (2) }## and leave the arguments of ##g## alone ... ... "

Now, following the above quoted text ... consider a specific permutation ##\sigma## ... say## \sigma_1 = \begin{bmatrix} 1 & 2 & 3 & 4 & 5 \\ 2 & 3 & 4 & 5 & 1 \end{bmatrix}##Now there are ##2!= 2## permutations ##\tau## in ##S_2## that permute the first ##k = 2## arguments ##( v_{ \sigma (1) }, v_{ \sigma (2) } ) = ( v_2, v_3 )## ...

[Note ... one of the ##k!## permutations is essentially ##\sigma_1## itself ... ]

These permutations may be represented by (is this correct?)

... in ##S_2## ...

##\tau_1 = \begin{bmatrix} 2 & 3 \\ 2 & 3 \end{bmatrix}##

##\tau_2 = \begin{bmatrix} 2 & 3 \\ 3 & 2 \end{bmatrix}##and in ##S_{ 2 + 3 }## ...## \tau_1 = \begin{bmatrix} 2 & 3 & 4 & 5 & 1 \\ 2 & 3 & 4 & 5 & 1 \end{bmatrix}##

## \tau_2 = \begin{bmatrix} 2 & 3 & 4 & 5 & 1 \\ 3 & 2 & 4 & 5 & 1 \end{bmatrix}##Now the resulting permutations ##\sigma \tau## are supposed to contribute the same term to the sum ...... ... ##\sigma_1 \tau_1 = \begin{bmatrix} 1 & 2 & 3 & 4 & 5 \\ 2 & 3 & 4 & 5 & 1 \end{bmatrix} \begin{bmatrix} 2 & 3 & 4 & 5 & 1 \\ 2 & 3 & 4 & 5 & 1 \end{bmatrix}##

## = \begin{bmatrix} 1 & 2 & 3 & 4 & 5 \\ 2 & 3 & 4 & 5 & 1 \end{bmatrix}##and## \sigma_1 \tau_2 = \begin{bmatrix} 1 & 2 & 3 & 4 & 5 \\ 2 & 3 & 4 & 5 & 1 \end{bmatrix} \begin{bmatrix} 2 & 3 & 4 & 5 & 1 \\ 3 & 2 & 4 & 5 & 1 \end{bmatrix}#### = \begin{bmatrix} 1 & 2 & 3 & 4 & 5 \\ 2 & 4 & 3 & 5 & 1 \end{bmatrix} ##

Now the two permutations are not identical ... but ... maybe the difference is accounted for in the ##( \text{ sgn } ) ## function somehow ... but how ... ?

Can someone please clarify the above ...

... ... could someone also confirm that the above analysis is basically correct ... ?

Peter