jasc15

- 162

- 5

I've come across this design issue several times, and don't know of any solution in industry. The basic assembly is this:

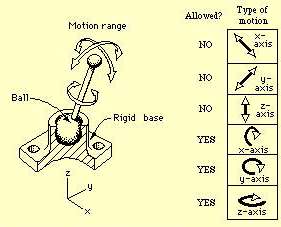

A spherical bearing is fitted to a threaded rod end with a nut to clamp the ball to the rod end. The design intent is to allow angular displacement about the two axes perpendicular to the rod axis (X and Y in the figure), but to constrain rotation about the axis parallel to the rod axis (Z in the figure), as well as constrain translation in all three linear axes. Essentially the constraint provided by a gimbal assembly, or an automotive CV joint, but in a more compact and lower parts-count unit. A splined ball also comes to mind.

In the past, we have simply restrained rotation about the rod axis by fixing a part to the rod with a tab which is bolted to the spherical ball bearing housing. However, the compliance I am seeking requires this tab to twist and bend, which is not ideal.

More simply, referring to the figure, I want the following types of motion allowed:

NO

NO

NO

YES

YES

NO

Thanks.

A spherical bearing is fitted to a threaded rod end with a nut to clamp the ball to the rod end. The design intent is to allow angular displacement about the two axes perpendicular to the rod axis (X and Y in the figure), but to constrain rotation about the axis parallel to the rod axis (Z in the figure), as well as constrain translation in all three linear axes. Essentially the constraint provided by a gimbal assembly, or an automotive CV joint, but in a more compact and lower parts-count unit. A splined ball also comes to mind.

In the past, we have simply restrained rotation about the rod axis by fixing a part to the rod with a tab which is bolted to the spherical ball bearing housing. However, the compliance I am seeking requires this tab to twist and bend, which is not ideal.

More simply, referring to the figure, I want the following types of motion allowed:

NO

NO

NO

YES

YES

NO

Thanks.