- #1

question dude

- 80

- 0

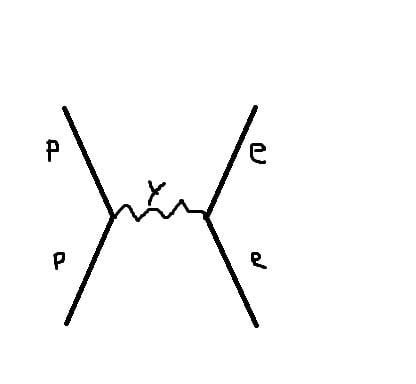

Would it just be the same as with two electrons? (or any other pair of particles with the same charge)

I'm kinda in two minds, I suspect that is wrong because wouldn't the fact that they attract each other (instead of repelling) means that the diagram would be drawn differently?

I'm kinda in two minds, I suspect that is wrong because wouldn't the fact that they attract each other (instead of repelling) means that the diagram would be drawn differently?