- #1

rollcast

- 408

- 0

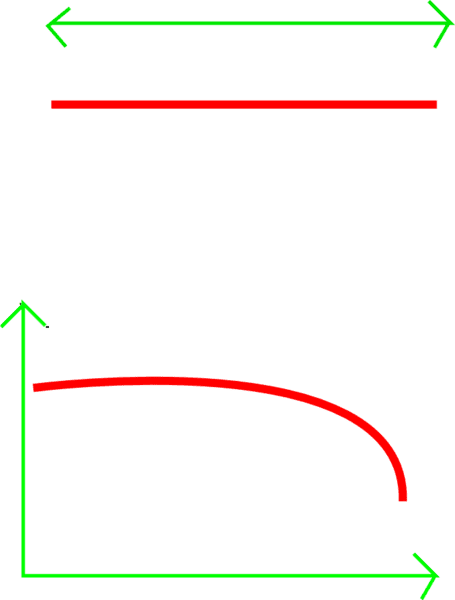

I've heard of curves being described as one dimensional but I don't understand how anything other than a straight line can be one dimensional as surely once the curve becomes, well, curved it is now in two dimensions?

I have illustrated this in the above diagram with the curve and straight line shown in red and the dimensions in green.

Thanks

A.

I have illustrated this in the above diagram with the curve and straight line shown in red and the dimensions in green.

Thanks

A.