Fantasist

- 177

- 4

pervect said:I think it would be useful to illustrate the difference between "rotating" and "orbiting", the two seem to be conflated in this thread.

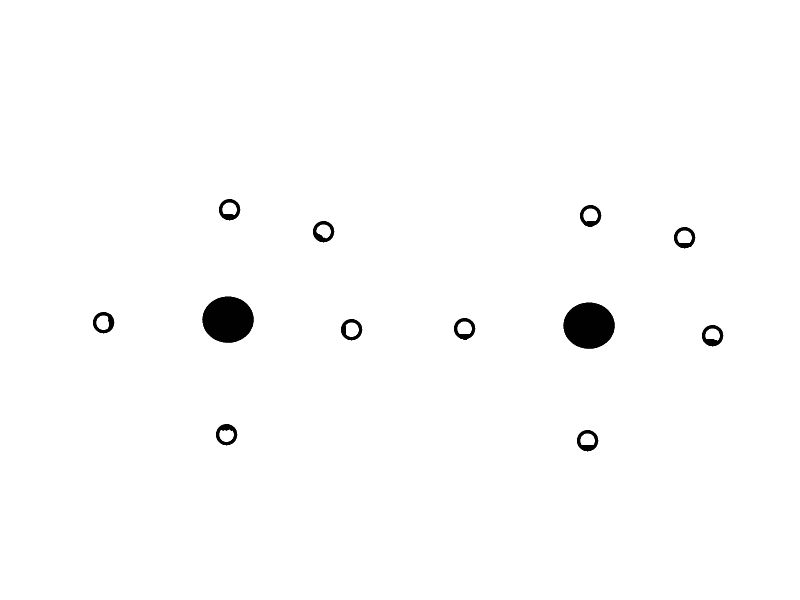

I will do this by exhibiting a diagram of two orbiting bodies. Several "snapshots" are taken throughout the orbit to show the position and orientation of the body at different times. There is a "black mark" on the body to allow its orientation to be determined. While both bodies are orbiting, only one body is rotating, which clearly (to my mind at least) illustrates that the concept of "orbiting" is distinct and different from the concept of "rotating".

I haven't included examples of non-orbiting bodies in a state of rotation and non-rotation, but I hope such can be easily imagined without a diagram. Thus we see that orbiting and rotation are different concepts, a body can have any of the four possible combinations of rotation/non-rotation and orbiting / non-orbiting.

In the attached diagram, the body on the left is orbiting and rotating (with respect to the fixed stars). The body on the right is orbiting and not rotating (with respect to the fixed stars).

I hope this will be helpful and will prompt a more coherent explanation of what the question(s) are. At least some of the posters in this thread seem to be interested more in Newtonian ideas ('instantaneous action at a distance") than GR ideas ("following a geodesic").

The diagram itself is basically Newtonian as it uses the Newtonian idea of "rotation relataive to the fixed stars".

I wouldn't mind talking some about the difference between the Newtonian and GR views, but I'm not actually sensing any interest in the GR point of view ("follwing a geodesic") at this point in time. Or perhaps the interest is there, and there's a language barrier.

Let me reply with my own diagram

consider a hammer thrower who is rotating around his own axis, keeping a mass attached to a string in a circular orbit around him. In this case, the force that keeps the mass in orbit acts directly only on the part of the mass where the string is attached. The rest of the mass is just passive mass, and thus an internal stress force (i.e. an electrostatic force) must be set up in it to keep it together (this internal stress force is what we feel as 'weight' when we accelerate e.g. in a car).

Now, in contrast to this consider a 'gravitational hammer thrower', who keeps the mass in orbit by means of the gravitational force rather than a mechanical connection. In this case, the force acts directly on all atoms of the mass, so no internal stress force is set up. Ignoring tidal effects, all parts of the mass should orbit the center of force on their own account, maintaining the same orientation with regard to the local radius vector. The point is that this rotation is also inertial like the linear orbital motion, so it would not be detected by an accelerometer. It is simply a consequence of the spherical gravitational potential (in contrast, in the case of the non-rotating orbiting planet in your own diagram, the accelerometer would actually measure a rotation, as that rotation is not an inertial rotation).

So it is obvious that a purely local measurement can not only provide no answer to the question whether one is actually accelerating or not, but neither to the question whether one is actually rotating or not. The interpretation of any accelerometer measurement can only be unambiguous if the global situation is taken into account.