- #1

- 18,994

- 23,994

Summary: Circulation, Number Theory, Differential Geometry, Functional Equation, Group Theory, Infinite Series, Algorithmic Precision, Function Theory, Coin Flips, Combinatorics.1. (solved by @etotheipi ) Given a vector field

$$

F\, : \,\mathbb{R}^3 \longrightarrow \mathbb{R}^3\, , \,F(x,y,z)=\begin{pmatrix}x-y^2\\x^2\\z\end{pmatrix}

$$

Calculate the circulation of ##F## along the mathematically positive oriented unit circle in the ##(x,y)##-plane

(a) by using the curl of a vector field.

(b) directly by an appropriate path.

2. An odd prime ##p## can be written as ##p=x^2+y^2## with integers ##x,y\in \mathbb{Z}## if and only is ##p\equiv 1 \mod 4.##

3. Let ##\mathbb{T}^n :=\mathbb{R}^n/\mathbb{Z}^n## equipped with the quotient topology according to the projection

$$

\pi\, : \,\mathbb{R}^n \longrightarrow \mathbb{T}^n\, , \,\pi(a)=a+\mathbb{Z}^n.

$$

Show that ##\mathbb{T}^n## is a topological manifold.

4. Let ##\alpha\in \mathbb{R}-\{0\}.## Determine all functions ##f:\mathbb{R}_{>0}\longrightarrow \mathbb{R}_{>0}## which satisfy for all ##x,y\in \mathbb{R}_{>0}##

$$

f(f(x)+y)=\alpha x+\dfrac{1}{f\left(\dfrac{1}{y}\right)}

$$

5. (solved by @fishturtle1 ) Show that the quaternion group ##G=\{\pm 1,\pm i,\pm j,\pm k\}## is a Hamilton group, and cannot be written as a semidirect product in a nontrivial way.

6. (solved by @LCSphysicist and @etotheipi )

(a) Calculate

$$

\dfrac{1}{2}-\dfrac{1}{12}+\dfrac{1}{40}-\dfrac{1}{112} \mp \ldots=\sum_{k=0}^{\infty}(-1)^k\dfrac{1}{(2k+1)2^{k+1}}\,.

$$

6. (b) Prove ##\dfrac{1}{2!}+\dfrac{2}{3!}+\dfrac{3}{4!}+\ldots=1\,.##

7. Prove

$$

\tan^{-1}(1/2)+\tan^{-1}(1/3)=\pi/4=4\tan^{-1}(1/5)-\tan^{-1}(1/239)

$$

and use the power series representation

$$

\tan^{-1}(x)=x-\dfrac{x^3}{3}+\dfrac{x^5}{5}-\dfrac{x^7}{7} \mp \ldots=\sum_{k=0}^{\infty}(-1)^k\dfrac{x^{2k+1}}{2k+1}

$$

to determine how many terms would it take to compute ##\pi## up to ##100## digits by ##\pi=4\tan^{-1}(1)## and by the formulas above.

8. (solved by @Gaussian97 ) Calculate the following integrals

(a) ##\displaystyle{\int_0^{2\pi}e^{(e^{it})}\,dt}##

(b) ##\displaystyle{\int_{|z|=1}\dfrac{\sin(z^2)}{(\sin z)^2}\,dz}##

(c) ##\displaystyle{\int_{|z|=1}\sin \left(e^{1/z}\right)\,dz}##

(d) ##\displaystyle{\int_{-\infty}^\infty \dfrac{1}{x^2-2x+2}\,dx}##

9. Suppose someone gives you a coin and claims that this coin is biased; that it lands on heads only ##48\%## of the time with an error margin of ##2\%##. You decide to test the coin for yourself. If you want to be ##95\%## confident that this coin is indeed biased, how many times must you flip the coin? Compare the estimations by the weak law of large numbers and by the central limit theorem!

10. (solved by @Gaussian97 ) A hat-check boy at a congress held at Hilbert's hotel completely loses track of which of hats belong to which owners, and hands them back at random to their owners as the latter leave. What is the probability ##P## that nobody receives their own hat back?

High Schoolers only

11. (solved by @lekh2003 ) Prove that

$$

\dfrac{1}{1+x+\dfrac{1}{y}}+\dfrac{1}{1+y+\dfrac{1}{z}}+\dfrac{1}{1+z+\dfrac{1}{x}}\leq 1

$$

for all positive real numbers ##x,y,z.##

12. Which is the smallest natural number greater than one such that the following statement holds:

In any set of ##n## natural numbers are at least two numbers, whose sum or difference is dividable by seven.

13. Determine

$$

\left[ \dfrac{1}{\sqrt{1}+\sqrt{2}} + \dfrac{1}{\sqrt{3}+\sqrt{4}} + \dfrac{1}{\sqrt{5}+\sqrt{6}}+ \ldots + \dfrac{1}{\sqrt{n^2-4}+\sqrt{n^2-3}} +\dfrac{1}{\sqrt{n^2-2}+\sqrt{n^2-1}} \right]

$$

for any odd natural number ##n\geq 3## where ##[n]=\lfloor n\rfloor ## is the greatest integer smaller or equal ##n.##

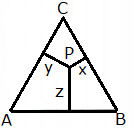

14. (solved by @YoungPhysicist ) Given a point ##P## inside an equilateral triangle ##\triangle ABC## with area ##1.## Show that for the lengths ##x,y,z## of the perpendiculars of ##P## onto the sides of the triangle holds ## x+y+z=\sqrt[4]{3}.##

15. Prove: If for the edges of a tetrahedron ##ABCD## holds

15. Prove: If for the edges of a tetrahedron ##ABCD## holds

$$

\overline{AD}=\overline{BD}=\overline{CD}=1 \text{ and } \overline{AB}=\overline{BC}=\overline{CA}\,,

$$

then its surface is smaller than ##\dfrac{3\sqrt{3}}{2}.##

$$

F\, : \,\mathbb{R}^3 \longrightarrow \mathbb{R}^3\, , \,F(x,y,z)=\begin{pmatrix}x-y^2\\x^2\\z\end{pmatrix}

$$

Calculate the circulation of ##F## along the mathematically positive oriented unit circle in the ##(x,y)##-plane

(a) by using the curl of a vector field.

(b) directly by an appropriate path.

2. An odd prime ##p## can be written as ##p=x^2+y^2## with integers ##x,y\in \mathbb{Z}## if and only is ##p\equiv 1 \mod 4.##

3. Let ##\mathbb{T}^n :=\mathbb{R}^n/\mathbb{Z}^n## equipped with the quotient topology according to the projection

$$

\pi\, : \,\mathbb{R}^n \longrightarrow \mathbb{T}^n\, , \,\pi(a)=a+\mathbb{Z}^n.

$$

Show that ##\mathbb{T}^n## is a topological manifold.

4. Let ##\alpha\in \mathbb{R}-\{0\}.## Determine all functions ##f:\mathbb{R}_{>0}\longrightarrow \mathbb{R}_{>0}## which satisfy for all ##x,y\in \mathbb{R}_{>0}##

$$

f(f(x)+y)=\alpha x+\dfrac{1}{f\left(\dfrac{1}{y}\right)}

$$

5. (solved by @fishturtle1 ) Show that the quaternion group ##G=\{\pm 1,\pm i,\pm j,\pm k\}## is a Hamilton group, and cannot be written as a semidirect product in a nontrivial way.

6. (solved by @LCSphysicist and @etotheipi )

(a) Calculate

$$

\dfrac{1}{2}-\dfrac{1}{12}+\dfrac{1}{40}-\dfrac{1}{112} \mp \ldots=\sum_{k=0}^{\infty}(-1)^k\dfrac{1}{(2k+1)2^{k+1}}\,.

$$

6. (b) Prove ##\dfrac{1}{2!}+\dfrac{2}{3!}+\dfrac{3}{4!}+\ldots=1\,.##

7. Prove

$$

\tan^{-1}(1/2)+\tan^{-1}(1/3)=\pi/4=4\tan^{-1}(1/5)-\tan^{-1}(1/239)

$$

and use the power series representation

$$

\tan^{-1}(x)=x-\dfrac{x^3}{3}+\dfrac{x^5}{5}-\dfrac{x^7}{7} \mp \ldots=\sum_{k=0}^{\infty}(-1)^k\dfrac{x^{2k+1}}{2k+1}

$$

to determine how many terms would it take to compute ##\pi## up to ##100## digits by ##\pi=4\tan^{-1}(1)## and by the formulas above.

8. (solved by @Gaussian97 ) Calculate the following integrals

(a) ##\displaystyle{\int_0^{2\pi}e^{(e^{it})}\,dt}##

(b) ##\displaystyle{\int_{|z|=1}\dfrac{\sin(z^2)}{(\sin z)^2}\,dz}##

(c) ##\displaystyle{\int_{|z|=1}\sin \left(e^{1/z}\right)\,dz}##

(d) ##\displaystyle{\int_{-\infty}^\infty \dfrac{1}{x^2-2x+2}\,dx}##

9. Suppose someone gives you a coin and claims that this coin is biased; that it lands on heads only ##48\%## of the time with an error margin of ##2\%##. You decide to test the coin for yourself. If you want to be ##95\%## confident that this coin is indeed biased, how many times must you flip the coin? Compare the estimations by the weak law of large numbers and by the central limit theorem!

10. (solved by @Gaussian97 ) A hat-check boy at a congress held at Hilbert's hotel completely loses track of which of hats belong to which owners, and hands them back at random to their owners as the latter leave. What is the probability ##P## that nobody receives their own hat back?

High Schoolers only

11. (solved by @lekh2003 ) Prove that

$$

\dfrac{1}{1+x+\dfrac{1}{y}}+\dfrac{1}{1+y+\dfrac{1}{z}}+\dfrac{1}{1+z+\dfrac{1}{x}}\leq 1

$$

for all positive real numbers ##x,y,z.##

12. Which is the smallest natural number greater than one such that the following statement holds:

In any set of ##n## natural numbers are at least two numbers, whose sum or difference is dividable by seven.

13. Determine

$$

\left[ \dfrac{1}{\sqrt{1}+\sqrt{2}} + \dfrac{1}{\sqrt{3}+\sqrt{4}} + \dfrac{1}{\sqrt{5}+\sqrt{6}}+ \ldots + \dfrac{1}{\sqrt{n^2-4}+\sqrt{n^2-3}} +\dfrac{1}{\sqrt{n^2-2}+\sqrt{n^2-1}} \right]

$$

for any odd natural number ##n\geq 3## where ##[n]=\lfloor n\rfloor ## is the greatest integer smaller or equal ##n.##

14. (solved by @YoungPhysicist ) Given a point ##P## inside an equilateral triangle ##\triangle ABC## with area ##1.## Show that for the lengths ##x,y,z## of the perpendiculars of ##P## onto the sides of the triangle holds ## x+y+z=\sqrt[4]{3}.##

$$

\overline{AD}=\overline{BD}=\overline{CD}=1 \text{ and } \overline{AB}=\overline{BC}=\overline{CA}\,,

$$

then its surface is smaller than ##\dfrac{3\sqrt{3}}{2}.##

Last edited: