Discussion Overview

The discussion revolves around proving an integral using a direct proof and epsilon-delta arguments. Participants explore different approaches to the problem, including proofs by contradiction and the implications of continuity on integrals. The scope includes theoretical aspects of integration and the application of limits in proofs.

Discussion Character

- Technical explanation

- Mathematical reasoning

- Debate/contested

Main Points Raised

- Some participants discuss the necessity of a direct proof after attempting a proof by contradiction, suggesting that it should be straightforward.

- One participant asserts that if a function \( f(x) > 0 \) for all \( x \in [a,b] \), then the integral \( \int_a^b f > 0 \), and proposes a correct statement regarding the conditions under which \( \int_a^b f = 0 \).

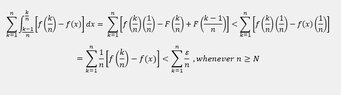

- Another participant mentions using a delta of \( 1/n \) and suggests employing an epsilon argument to show equality between the Riemann sum and the integral.

- There is a discussion about the choice of \( \delta \) being independent of \( n \) and the implications of uniform continuity on the function \( f \).

- Participants explore the relationship between the Riemann sum and the integral, noting that the difference can be made less than \( \epsilon \) under certain conditions.

- One participant expresses confusion about the role of continuity in proofs involving integrals and suggests that proofs should be introduced earlier in learning.

- Another participant proposes a limit approach to show that \( f(x) = 0 \) for all \( x \in [a,b] \) based on the integral being zero over small intervals.

- There is a correction regarding a typo in a mathematical expression, indicating the collaborative nature of the discussion.

- One participant questions whether an epsilon-delta argument should be used for a specific proof, while another suggests using basic properties of the integral instead.

Areas of Agreement / Disagreement

Participants express differing views on the methods for proving the integral, with some advocating for direct proofs and others suggesting alternative approaches. The discussion remains unresolved regarding the best method to employ, as multiple competing views are presented.

Contextual Notes

Limitations include the dependence on the continuity of the function and the assumptions made about the function's behavior over the interval. There are unresolved mathematical steps and conditions that participants acknowledge but do not fully clarify.