cosmicminer

- 20

- 1

There are a number n of runners in a race.

We know their expected times from start to finish μ(i) and the corresponding standard deviations σ(i).

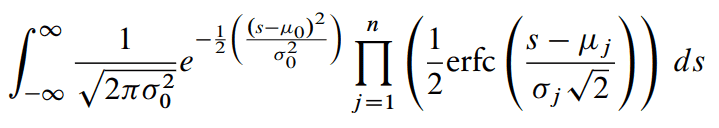

The probability of runner 0 to finish first is given by this integral:

It's from here:

https://www.untruth.org/~josh/math/normal-min.pdf

The 0 is one of the i's really but is suffixed as 0 in the above image of the formula.

I would write i instead of "0" and then in the product j ≠ i rather.

This can be computed easily using Simpson's rule and the approximation for erfc from Abramowitz-Stegun perhaps.

The strange thing is this:

If I choose n = 2 and any values for μ and σ then the following holds true:

if μ(1) < μ(2) then always P(1) > P(2) irrespective of the σ's ................. (1)

This is a property of the double normal distribution.

Thus if runner 1 has a delta function for a distribution (limiting normal with σ = 0) and runner b is close second but with big σ then the 1 has higher probability irrespective.

But if n > 2 the law (1) may or may not hold - depending on the sigmas.

So for n > 2 it is possible that one of the theoretically faster runners has lower probability than a slower runner with bigger σ.

How is this possible ?

We know their expected times from start to finish μ(i) and the corresponding standard deviations σ(i).

The probability of runner 0 to finish first is given by this integral:

It's from here:

https://www.untruth.org/~josh/math/normal-min.pdf

The 0 is one of the i's really but is suffixed as 0 in the above image of the formula.

I would write i instead of "0" and then in the product j ≠ i rather.

This can be computed easily using Simpson's rule and the approximation for erfc from Abramowitz-Stegun perhaps.

The strange thing is this:

If I choose n = 2 and any values for μ and σ then the following holds true:

if μ(1) < μ(2) then always P(1) > P(2) irrespective of the σ's ................. (1)

This is a property of the double normal distribution.

Thus if runner 1 has a delta function for a distribution (limiting normal with σ = 0) and runner b is close second but with big σ then the 1 has higher probability irrespective.

But if n > 2 the law (1) may or may not hold - depending on the sigmas.

So for n > 2 it is possible that one of the theoretically faster runners has lower probability than a slower runner with bigger σ.

How is this possible ?