- #1

JD_PM

- 1,131

- 158

- TL;DR Summary

- Do these two rays set off simultaneously if we move from train's frame to ground's frame?

I am studying the fact that two events that are simultaneous in a frame aren't (in general) simultaneous in another.

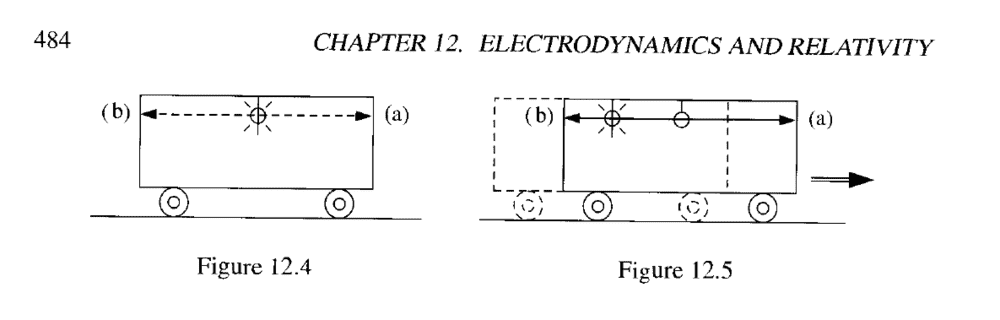

The lamp is equidistant from the two ends. When the light is switched on an observer on the train sees how both light rays hit the back and the front of the train simultaneously. This is not the case for an observer on the ground, who claims that the light ray going to the left hits the back before the light ray going to the right hits the front.

I am OK with this but I want now to focus on the simultaneity of the fire of both light rays. From the train's frame, both rays leave the lamp at the same time, one going to the right and the other to the left. My question now is:

Do they leave the bulb simultaneously from the ground's frame as they do wrt train's frame?

I'd say that the rays do leave at the same time as well, and this is my reasoning:

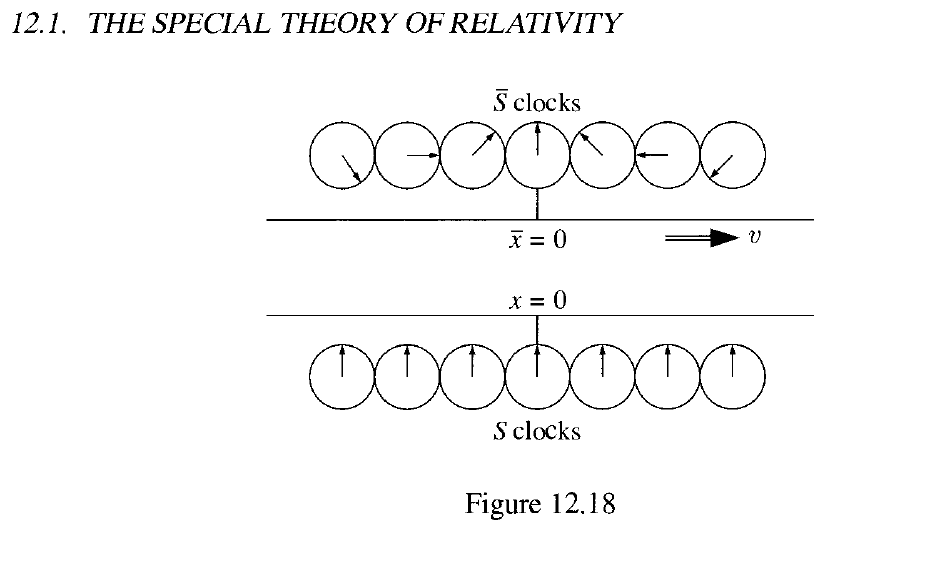

Let me be on the ground's frame and examine all the clocks in the train. I will realize that the clocks read different times depending upon their location because:

$$\bar t = -\gamma \frac{v}{c^2}x$$

Where ##\bar t## is the time elapsed in the train (according to the clocks in the train read by me, an observer located at the ground's frame). This is an illustration:

My point is that the master clock reads ##\bar t = 0##, so ##\bar t = 0 = t## which means that both light rays leave also at time zero (and thus simultaneously) from the ground's frame.

What do you think of my reasoning?

The lamp is equidistant from the two ends. When the light is switched on an observer on the train sees how both light rays hit the back and the front of the train simultaneously. This is not the case for an observer on the ground, who claims that the light ray going to the left hits the back before the light ray going to the right hits the front.

I am OK with this but I want now to focus on the simultaneity of the fire of both light rays. From the train's frame, both rays leave the lamp at the same time, one going to the right and the other to the left. My question now is:

Do they leave the bulb simultaneously from the ground's frame as they do wrt train's frame?

I'd say that the rays do leave at the same time as well, and this is my reasoning:

Let me be on the ground's frame and examine all the clocks in the train. I will realize that the clocks read different times depending upon their location because:

$$\bar t = -\gamma \frac{v}{c^2}x$$

Where ##\bar t## is the time elapsed in the train (according to the clocks in the train read by me, an observer located at the ground's frame). This is an illustration:

My point is that the master clock reads ##\bar t = 0##, so ##\bar t = 0 = t## which means that both light rays leave also at time zero (and thus simultaneously) from the ground's frame.

What do you think of my reasoning?

Last edited by a moderator: