- #1

Xforce

- 73

- 6

- TL;DR Summary

- There are more ways to fuse atoms other than a tokamak

At the early 20th century, people can only achieve fusion by smashing atoms together via particle accelerators. That obviously outputs much less energy than input, and takes forever just to fuse a single gram of hydrogen to helium.

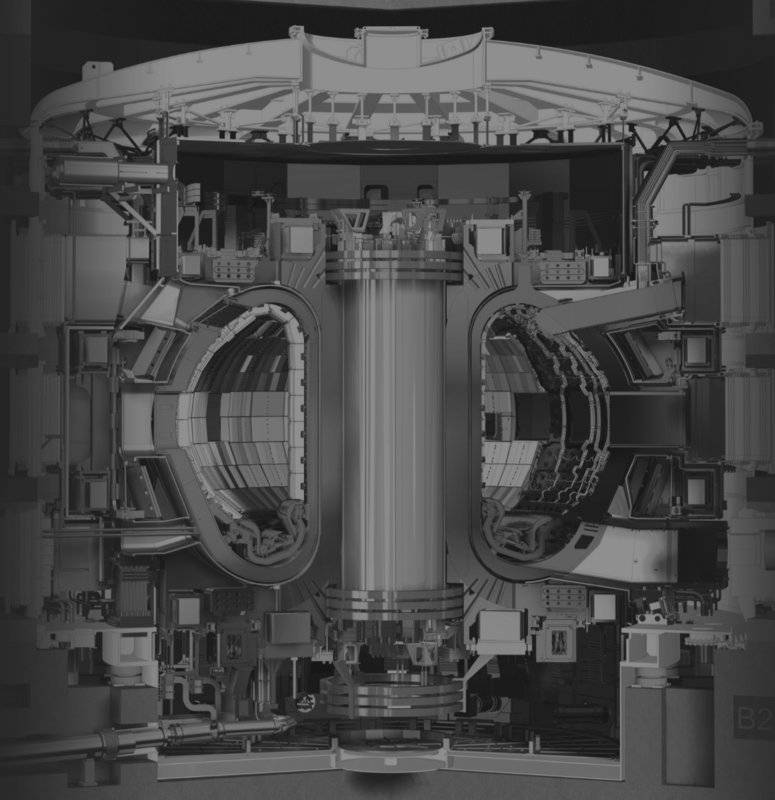

Currently, speaking of thermonuclear reactors we always think of a tokamak like ITER (see the picture below)

It undoubtedly have sustained fusion and high efficiency, but I have also heard fusion methods like Z-pinch, stellarators and inertial fusion (as a proposed futuristic space propulsion). What are the other ways of achieving fusion, how do they work and what advantages/disadvantages do they have?

Currently, speaking of thermonuclear reactors we always think of a tokamak like ITER (see the picture below)

It undoubtedly have sustained fusion and high efficiency, but I have also heard fusion methods like Z-pinch, stellarators and inertial fusion (as a proposed futuristic space propulsion). What are the other ways of achieving fusion, how do they work and what advantages/disadvantages do they have?