esis

- 10

- 0

Hey Guys!

To begin with, I apologize if I am using the wrong terminology. I've just begun learning about linear algebra.

So I was working on a problem in the book "Introduction to Linear Algebra" by Gilbert Strang, fourth edition (problems 9 and 11 on p. 8).

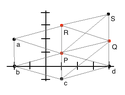

Problem 9: If three corners of a parallelogram are (1 , 1), (4, 2), and (1, 3), what are all three of the possible fourth corners? Draw Two of them.

Problem 11: Four corners of the cube are (0, 0, 0), (1, 0, 0), (0, 1, 0), (0, 0, 1). What are the other four corners? Find the coordinates of the center point of the cube.

I solved these by drawing diagrams and identifying where to place the missing points, but this got me thinking of non-visual ways of solving the problem (if if you know of such a method, please let me know!)

How do you identify the vectors that delimit the span of a particular line(?)/plane(?)/Cube(?) etc. without actually visualizing the space?

I figured this algorithm might do the job:

#1 Start with all points equal to 1.

#2 Set the first component to zero.

#3 Move the zero, step by step, through all the components of the matrice until you reach the last component.

#4 Let the last component remain = 0, and set the first component to zero.

#5 Repeat #3 until you reach the component before the last zeroed component.

#6 Repeat until all component are zero

You now have all the borders of the space in any dimension.

i.e.

Dimension: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 ...

Space A = (1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, ...)

A1:

(1)

(0)

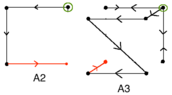

A2:

(1, 1)

(0, 1)

(0, 0)

A3:

(1, 1, 1)

(0, 1, 1)

(1, 0, 1)

(1, 1, 0)

(0, 1, 0)

(1, 0, 0)

(0, 0, 0)

(0, 0, 1)

A4:

(1, 1, 1, 1)

(0, 1, 1, 1)

(1, 0, 1, 1)

(1, 1, 0, 1)

(1, 1, 1, 0)

(0, 1, 1, 0)

(1, 0, 1, 0)

(1, 1, 0, 0)

(0, 1, 0, 0)

(1, 0, 0, 0)

(0, 0, 0, 0)

(0, 0, 0, 1)

(0, 0, 1, 1)

I figured I could use this to somehow solve problems 9 and 11 above... I'll continue working on this problem tonight, but do you think I am on the right track? I figured maybe I could use this algorithm to derive all the necessary points knowing only a single point and the dimension of the space. Again, I'm a complete newb just paying around, it would be interesting to hear your thoughts :)

EDIT: I just realized that for this to work, the algorithm needs be run backwards for dimensions over two! It will need 1 run for A3, two for A4... and hmm, I wonder how many for A5...?

To begin with, I apologize if I am using the wrong terminology. I've just begun learning about linear algebra.

So I was working on a problem in the book "Introduction to Linear Algebra" by Gilbert Strang, fourth edition (problems 9 and 11 on p. 8).

Problem 9: If three corners of a parallelogram are (1 , 1), (4, 2), and (1, 3), what are all three of the possible fourth corners? Draw Two of them.

Problem 11: Four corners of the cube are (0, 0, 0), (1, 0, 0), (0, 1, 0), (0, 0, 1). What are the other four corners? Find the coordinates of the center point of the cube.

I solved these by drawing diagrams and identifying where to place the missing points, but this got me thinking of non-visual ways of solving the problem (if if you know of such a method, please let me know!)

How do you identify the vectors that delimit the span of a particular line(?)/plane(?)/Cube(?) etc. without actually visualizing the space?

I figured this algorithm might do the job:

#1 Start with all points equal to 1.

#2 Set the first component to zero.

#3 Move the zero, step by step, through all the components of the matrice until you reach the last component.

#4 Let the last component remain = 0, and set the first component to zero.

#5 Repeat #3 until you reach the component before the last zeroed component.

#6 Repeat until all component are zero

You now have all the borders of the space in any dimension.

i.e.

Dimension: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 ...

Space A = (1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, ...)

A1:

(1)

(0)

A2:

(1, 1)

(0, 1)

(0, 0)

A3:

(1, 1, 1)

(0, 1, 1)

(1, 0, 1)

(1, 1, 0)

(0, 1, 0)

(1, 0, 0)

(0, 0, 0)

(0, 0, 1)

A4:

(1, 1, 1, 1)

(0, 1, 1, 1)

(1, 0, 1, 1)

(1, 1, 0, 1)

(1, 1, 1, 0)

(0, 1, 1, 0)

(1, 0, 1, 0)

(1, 1, 0, 0)

(0, 1, 0, 0)

(1, 0, 0, 0)

(0, 0, 0, 0)

(0, 0, 0, 1)

(0, 0, 1, 1)

I figured I could use this to somehow solve problems 9 and 11 above... I'll continue working on this problem tonight, but do you think I am on the right track? I figured maybe I could use this algorithm to derive all the necessary points knowing only a single point and the dimension of the space. Again, I'm a complete newb just paying around, it would be interesting to hear your thoughts :)

EDIT: I just realized that for this to work, the algorithm needs be run backwards for dimensions over two! It will need 1 run for A3, two for A4... and hmm, I wonder how many for A5...?

Last edited: