pobro44

- 11

- 0

1. The problem statement, all variables and given/known dana

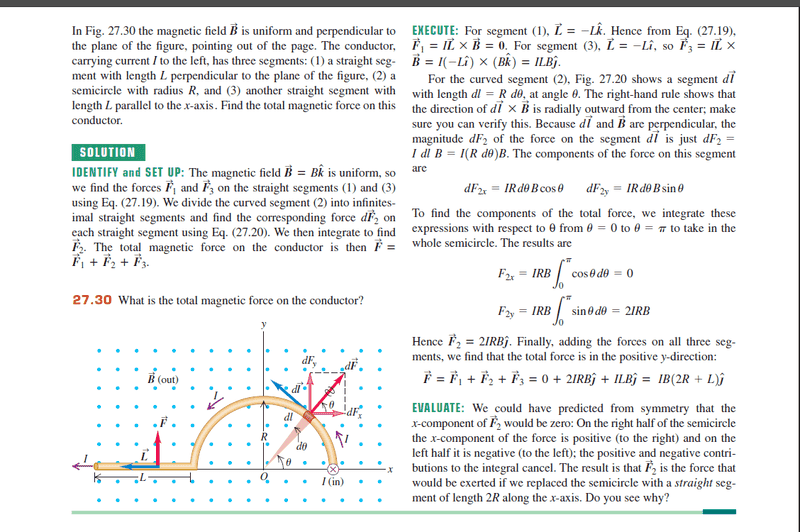

I was revisiting University physics textbook and came across this problem. We learned new coordinate systems in classical mechanics classes so I wanted to see if I can apply this to the problem of force on semicircular part of the conductor

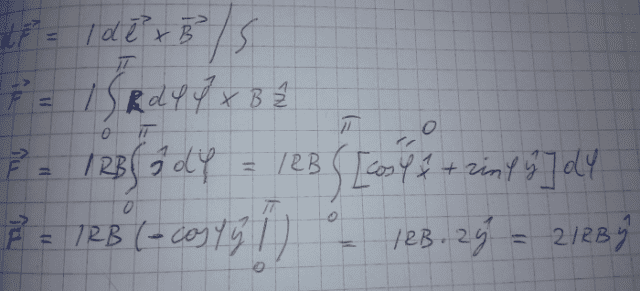

Cartesian and cylindrical coordinates

I tried using cylindrical coordinates. I rewrote radial vector (here marked by s unit vector…in a hurry I dropped the unit vector on second line) in cartesian coordinates and integrated. Result is correct.

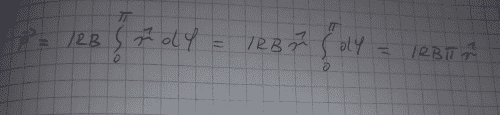

However if I choose not to use conversion to cartesian coordinates and just integrate like this, putting the radial vector in front of integral (now marked with r unit vector) I get the following:

So, I have a force in radial direction. Makes sense, it is always directed perpendicular to the semircircle tangent. And it is obvious by symetry that x cartesian components cancel out leaving only y component. However, these 2 results should be the same. If they are, then we should be able to rewrite the cylindrical radial unit vector as 2/pi * y hat unit vector in cartesian coordinates. I may be missing something obvious or made an embarassing mistake, but I see no way to convert the result that way (eliminating pi in particular).

So, I have a force in radial direction. Makes sense, it is always directed perpendicular to the semircircle tangent. And it is obvious by symetry that x cartesian components cancel out leaving only y component. However, these 2 results should be the same. If they are, then we should be able to rewrite the cylindrical radial unit vector as 2/pi * y hat unit vector in cartesian coordinates. I may be missing something obvious or made an embarassing mistake, but I see no way to convert the result that way (eliminating pi in particular).

I was revisiting University physics textbook and came across this problem. We learned new coordinate systems in classical mechanics classes so I wanted to see if I can apply this to the problem of force on semicircular part of the conductor

Homework Equations

Cartesian and cylindrical coordinates

The Attempt at a Solution

I tried using cylindrical coordinates. I rewrote radial vector (here marked by s unit vector…in a hurry I dropped the unit vector on second line) in cartesian coordinates and integrated. Result is correct.

However if I choose not to use conversion to cartesian coordinates and just integrate like this, putting the radial vector in front of integral (now marked with r unit vector) I get the following:

Attachments

Last edited: