I like

@sophiecentaur 's posts #10 and #13. They illustrate the kind of logic that engineers do every day to find a balance. In this case, fire safety versus affordability. Engineers especially are fond of the phrase "everything is a trade-off.."

They also illustrate a non-obvious secondary consequence of changing a parameter. In this case, changing standard voltage from 120 to 230 in practice shifts the risks of fire in the devices relative to the risk of fire in the wires feeding those devices.

jim hardy said:

That's for convenience and is called 'Co-ordination'.

Local faults should be cleared gracefully, not cascade into a whole house(or a whole state) blackout .

That's true Jim, but the interesting question is how far down do we extend protection? The circuit [almost always]? The plug? Internal to the appliance? Each individual component on a circuit card [almost never]?

In the USA, protection usually stops at the wiring infrastructure in the walls and panels. For example, I've never seen a desk lamp with its own breaker or fuse. But there are exceptions. If you look inside a desktop PC, you'll find several fuses protecting subsystems.

The UK made different choices than the USA.

@sophiecentaur explained some of the reasons. I won't get dragged into a debate about which is better, but I find the differences instructive.

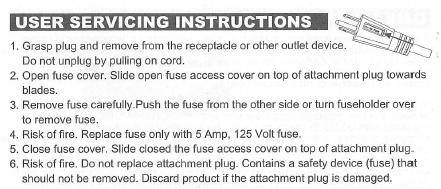

In terms of fans in the USA, I'm looking at a small tabletop fan right now. It has no fused plug like the one

@berkeman found. Perhaps there is a standard that kicks in only for fans of a certain size, or for use outdoors.

Edit: There are a half dozen or so books with "the art and science of protective relaying" in their title. They acknowledge that it is partially art.