GeorgeDishman

- 419

- 29

Thanks for replying, the result surprises me but as I said, I'm not at all familiar with the workings of GR so this is fascinating.

However, I take your point, the materials aspect makes this much more onerous so perhaps a simplified approach based on the space version might be more amenable to analysis (below).

Each tube individually, with its pair of masses, should be within a "pancake" region. In that view, I think the associated tubes would stretch and shrink, equivalent to the masses moving relative to the tube ends in the more usual representation. Since the tubes containing masses A-B and E-F are a wavelength apart, I am hoping we can define a congruence in which all four are always at rest and the distances A-E and B-F are also constant.

The question then is what happens to masses C and D and their associated tube? I think there should be a third "pancake region" covering them so, within that, the relative motion of the masses and tube should be as for the other two regions (just 180 degrees later), but is your calculation able to say how those two masses move relative to the congruence in which the other four are always at rest?

P.s. I'm also assuming we are simplifying by calculating for a constant wave frequency whereas the LIGO detection swept from a wavelength greater than the diameter of the Earth to 3 times smaller in less than 20ms, and that we are just working with plane waves.

Thank you, that is the problem I had seen albeit in my invalid approach.pervect said:At a peak chirp frequency of 300 hz, the Ligo burst can have wavelengths as small as a million meters, or 1000 km. So it's problematical to define an rigid frame the size of the Earth, though it's not problematical to define such a frame the size of Ligo.

Yes, understood.pervect said:.. it turns out (I believe the reason can be traced to the relativity of simultaneity) that when we do this, as we must to have a rigid flow, ##\nabla_z u^a## will not be zero.

Basically, we can choose our congruence to make ##\nabla_x## (and the equivalent in the y direction) zero at or near z=0, but due to the time and space variation of our metric, the choice that makes it zero at z=0 doesn't make it zero at different values of z. If we restrict the range of concern to a region of "small change in z", where the GW amplitude doesn't change much, we have a reasonable approximation to a rigid flow. If we don't restrict our range, we don't have a reasonable approximation to a rigid flow. So the shape of our almost-rigid region is more like a pancake than a sphere - it's limited to the dimension of the GW in the direction of propagation of the GW, but is large in the other two directions.

Also understood.pervect said:This is way too much work, ..

That they are isolated is true but the range over which the isolation is effective is limited to a small fraction of a wavelength of the interferometer laser, so if the motion of the masses is too large then it will exceed the ability of the system to remain locked. That displacement limit is what I am looking at.pervect said:.. and is totally irrelevant to the Ligo result anyway, because the whole purpose of the Ligo apparatus is to isolate the test masses from the environment of the Earth.

However, I take your point, the materials aspect makes this much more onerous so perhaps a simplified approach based on the space version might be more amenable to analysis (below).

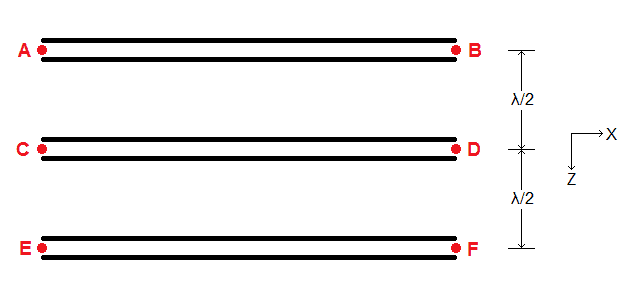

How about three copies of LIGO-in-space separated in the z direction by λ/2, would it be possible to say how that would behave? I've attached a sketch showing three tubes as black line pairs with red test masses (not to scale, λ≈2000km, tube length=4km).pervect said:Conceptually these issues wouldn't matter much to GW detection of what I've been calling "Ligo in space", because there's no problem with the size of the frame for that problem, most especially if you orient the detector optimally. Then it's easy to talk about how the test masses move relative to the beam tube, because we can approximate it in the familiar context of a rigid frame.

Each tube individually, with its pair of masses, should be within a "pancake" region. In that view, I think the associated tubes would stretch and shrink, equivalent to the masses moving relative to the tube ends in the more usual representation. Since the tubes containing masses A-B and E-F are a wavelength apart, I am hoping we can define a congruence in which all four are always at rest and the distances A-E and B-F are also constant.

The question then is what happens to masses C and D and their associated tube? I think there should be a third "pancake region" covering them so, within that, the relative motion of the masses and tube should be as for the other two regions (just 180 degrees later), but is your calculation able to say how those two masses move relative to the congruence in which the other four are always at rest?

P.s. I'm also assuming we are simplifying by calculating for a constant wave frequency whereas the LIGO detection swept from a wavelength greater than the diameter of the Earth to 3 times smaller in less than 20ms, and that we are just working with plane waves.

Last edited: