- #1

GeorgeDishman

- 419

- 29

First let me be clear, I am not questioning GR or the detection of gravitational waves by LIGO, I am trying to improve my own understanding of GW to the point where I can offer a graphic illustration (web video) showing what they do as they pass us to help others understand them. I started this a couple of years ago and thought I had a handle on it but have hit a problem with the LIGO parameters that tells me I have a misunderstanding somewhere. I don't know how to use GR mathematically (I have only a qualitative grasp) so I can't resolve the problem myself, and it probably comes from some remnant of Newtonian thinking that I've not recognised yet.

OK, the starting point was a pair of Wikipedia animations of the effects of GW:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:GravitationalWave_PlusPolarization.gif

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:GravitationalWave_CrossPolarization.gif

The two particles at the left and right end can be thought of roughly as the two test mass mirrors in one LIGO arm while the top and bottom particles would be the mirrors in the second arm.

Those animations are just in a plane, to see how that is related to a wave, you need a 3D version like this:

http://www.einstein-online.info/images/spotlights/gw_wavesI/cyl_plus

Combining the polarisations might give this:

http://www.einstein-online.info/images/spotlights/gw_wavesI/gw_elliptic

Those are from this page

http://www.einstein-online.info/spotlights/gw_waves

The Wikipedia images can be thought of as a slice from the end of the einstein-online 3D tubes.

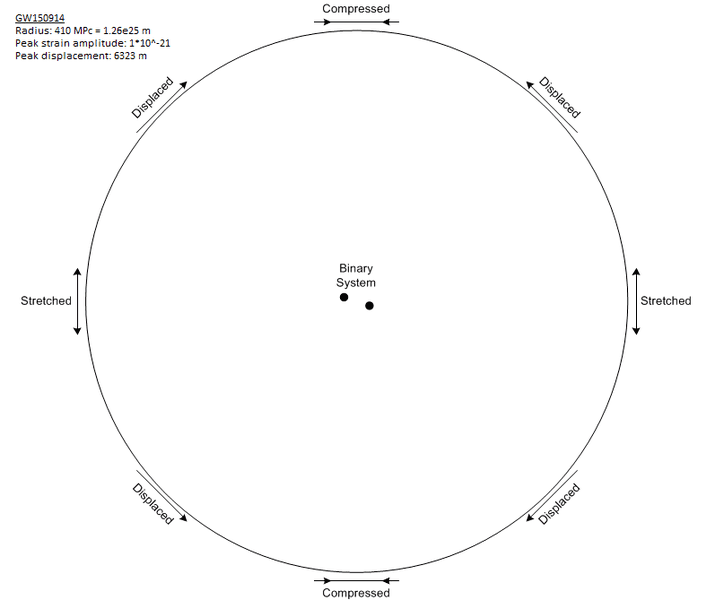

Those the effect of GW on a "ring of test particles" and I wanted to extend that to show the effect on a complete geodesic sphere enclosing a binary system system. The effect over any small region would be given by the equations in this part of the article (it's about the Earth-Sun system but the equations should be general):

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gravitational_wave#Wave_amplitudes_from_the_Earth.E2.80.93Sun_system

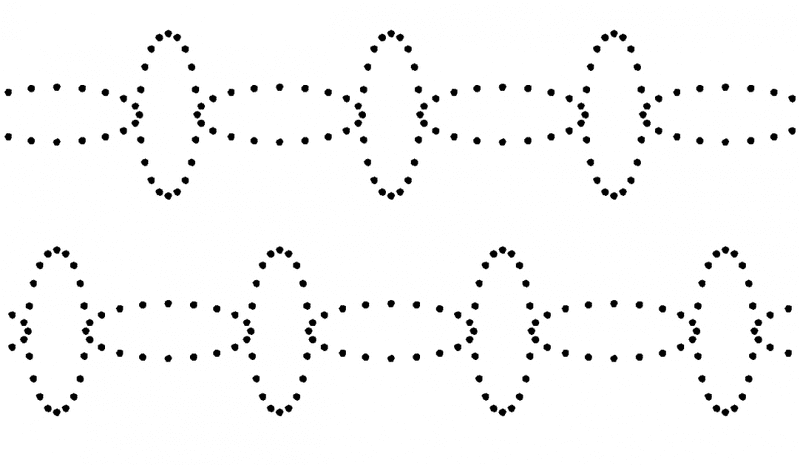

I intend to build up my understanding in steps so the simplest beginning was to consider a number of copies of the Wikipedia ring of particles with the horizontal ends sharing a particles (all are considered free-falling). It seemed to me that if one ring expanded, that next to it would have to expand too, alternating rings like this couldn't make sense:

However, if all the rings are the same, then there is not only distortion but also displacement as shown by the coloured lines relating three of the particles. The red particle is used as a fiducial datum but see later:

That view seemed to be borne out when, some months later, I saw this explanation by Rainer Weiss in the LIGO press conference. The link should take you to 23:06 and you only need to watch 45 seconds or so:

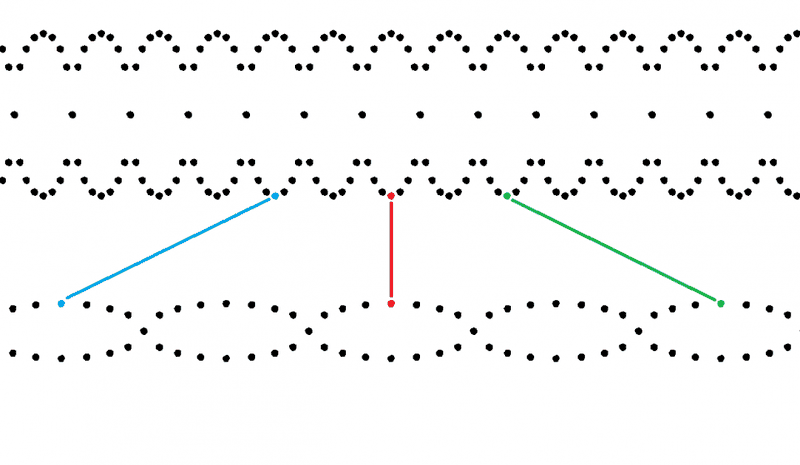

Now if we extend Rainer's mesh into a ribbon that runs completely around the GW source at uniform radius, there is an obvious problem, how can the whole circumference expand or contract? The answer is that it doesn't. The frequency of the waves is double the orbital frequency of the binary system because, in the simplest case of equal masses, it doesn't matter which star is which. That means if we see expansion then at the same time an observer on the opposite side from us but at the same radius would also see expansion while observers half way round the circle would see contraction like this:

The numbers in the top left corner are for HM Cancri, the fastest nearby binary system. Now the expanded regions are balanced by contracted regions so the proper length round the circumference is constant.To find the displacement at any location relative to our fiducial point, we need to integrate the strain around the circumference. The strain is h sin(2θ) so the integral should be -h/2 cos(2θ) but that implies no part of the circumference is static.

Putting that together as a video (the start of my ultimate goal) gives me this image of Rainer's mesh extended all the way round (not to scale, think of it as light years round, 1m high and displacements of microns):

Again, it's only 30 seconds long so please watch it, the text will make a lot more sense if you do.

So why don't we measure the displacement? My view was that the two LIGO test masses can be thought of as lying at two adjacent points on the circumference and the beam tube is essentially the chord joining them. Since the beam tube and even the whole Earth are also displaced, there is no relative motion to be detected.

It should be clear that one point will be affected slightly before the other as the band of compression (say) moves round the circumference, hence what is measured can be thought of as the distance variation caused by the slight phase difference between the masses displacements.

In case anyone thinks I'm suggesting superluminal motion of the compression band round the circumference, I'll add this similar video showing how that is an illusion and what is really happening is a transverse wave propagating out from the binary system at the speed of light:

OK, I've typed enough, can anyone tell me where have I gone wrong or is this OK so far?

OK, the starting point was a pair of Wikipedia animations of the effects of GW:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:GravitationalWave_PlusPolarization.gif

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:GravitationalWave_CrossPolarization.gif

The two particles at the left and right end can be thought of roughly as the two test mass mirrors in one LIGO arm while the top and bottom particles would be the mirrors in the second arm.

Those animations are just in a plane, to see how that is related to a wave, you need a 3D version like this:

http://www.einstein-online.info/images/spotlights/gw_wavesI/cyl_plus

Combining the polarisations might give this:

http://www.einstein-online.info/images/spotlights/gw_wavesI/gw_elliptic

Those are from this page

http://www.einstein-online.info/spotlights/gw_waves

The Wikipedia images can be thought of as a slice from the end of the einstein-online 3D tubes.

Those the effect of GW on a "ring of test particles" and I wanted to extend that to show the effect on a complete geodesic sphere enclosing a binary system system. The effect over any small region would be given by the equations in this part of the article (it's about the Earth-Sun system but the equations should be general):

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gravitational_wave#Wave_amplitudes_from_the_Earth.E2.80.93Sun_system

I intend to build up my understanding in steps so the simplest beginning was to consider a number of copies of the Wikipedia ring of particles with the horizontal ends sharing a particles (all are considered free-falling). It seemed to me that if one ring expanded, that next to it would have to expand too, alternating rings like this couldn't make sense:

However, if all the rings are the same, then there is not only distortion but also displacement as shown by the coloured lines relating three of the particles. The red particle is used as a fiducial datum but see later:

That view seemed to be borne out when, some months later, I saw this explanation by Rainer Weiss in the LIGO press conference. The link should take you to 23:06 and you only need to watch 45 seconds or so:

Now if we extend Rainer's mesh into a ribbon that runs completely around the GW source at uniform radius, there is an obvious problem, how can the whole circumference expand or contract? The answer is that it doesn't. The frequency of the waves is double the orbital frequency of the binary system because, in the simplest case of equal masses, it doesn't matter which star is which. That means if we see expansion then at the same time an observer on the opposite side from us but at the same radius would also see expansion while observers half way round the circle would see contraction like this:

The numbers in the top left corner are for HM Cancri, the fastest nearby binary system. Now the expanded regions are balanced by contracted regions so the proper length round the circumference is constant.To find the displacement at any location relative to our fiducial point, we need to integrate the strain around the circumference. The strain is h sin(2θ) so the integral should be -h/2 cos(2θ) but that implies no part of the circumference is static.

Putting that together as a video (the start of my ultimate goal) gives me this image of Rainer's mesh extended all the way round (not to scale, think of it as light years round, 1m high and displacements of microns):

Again, it's only 30 seconds long so please watch it, the text will make a lot more sense if you do.

So why don't we measure the displacement? My view was that the two LIGO test masses can be thought of as lying at two adjacent points on the circumference and the beam tube is essentially the chord joining them. Since the beam tube and even the whole Earth are also displaced, there is no relative motion to be detected.

It should be clear that one point will be affected slightly before the other as the band of compression (say) moves round the circumference, hence what is measured can be thought of as the distance variation caused by the slight phase difference between the masses displacements.

In case anyone thinks I'm suggesting superluminal motion of the compression band round the circumference, I'll add this similar video showing how that is an illusion and what is really happening is a transverse wave propagating out from the binary system at the speed of light:

OK, I've typed enough, can anyone tell me where have I gone wrong or is this OK so far?

Last edited: