ago01

- 46

- 8

- Homework Statement

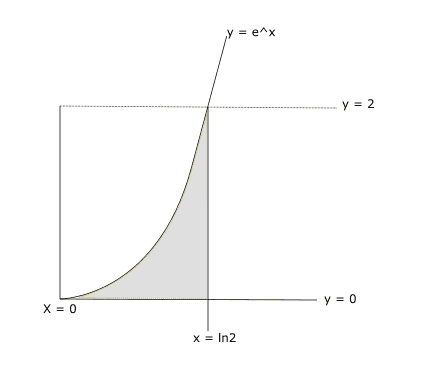

- Given The curve $$y = e^x$$ and the lines $$y = 0$$, $$x = 0$$, and $$x = ln 2$$ express the area as an iterated integral and solve.

- Relevant Equations

- N/A

I have the solution for this problem using dydx as the area. Worse yet, I cannot find another solution for it. Everyone seems to just magically pick dydx without thinking and naturally this is frustrating as learning the correct choice is 99.9% of the battle...

So, I was curious how one might go about solving it the other way. Here's a representation of the area:

So if we imagine going from left to right (for dx) then our x limits seem to go from $$y=e^x$$ to $$ln2$$ which implies $$x = lny$$ and $$x = ln2$$ for our lower and upper limits. Then it follows that y goes from $$0$$ to $$2$$. So:

$$\int^{2}_{0}\int^{ln2}_{lny}dxdy$$

But after solving this integral I get an area of 2, rather than the desired area of 1. I cannot figure out how my setup is wrong here. What am I missing?

So, I was curious how one might go about solving it the other way. Here's a representation of the area:

So if we imagine going from left to right (for dx) then our x limits seem to go from $$y=e^x$$ to $$ln2$$ which implies $$x = lny$$ and $$x = ln2$$ for our lower and upper limits. Then it follows that y goes from $$0$$ to $$2$$. So:

$$\int^{2}_{0}\int^{ln2}_{lny}dxdy$$

But after solving this integral I get an area of 2, rather than the desired area of 1. I cannot figure out how my setup is wrong here. What am I missing?