- #1

RingNebula57

- 56

- 2

Hello everyone!

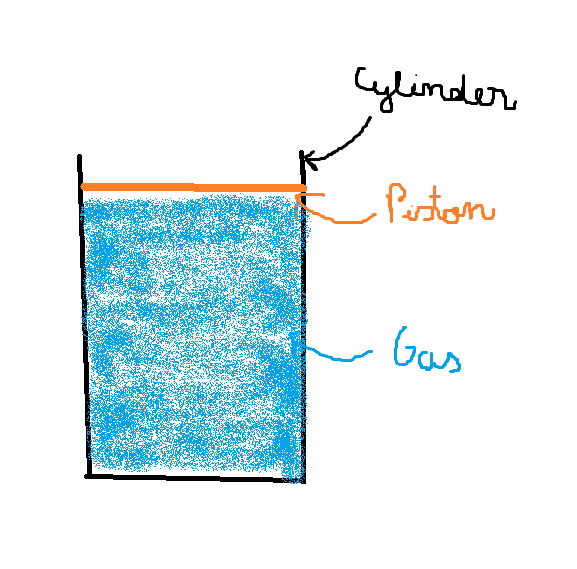

I've been thinking a lot about this thermodynamics problem , hearing all sorts of opinions but never getting a full rigurous explanation. So we have a cylinder that is placed in vacuum. We insert in the cylinder a monoatomic ideal gas. The gas is trapped inside the cylinder with a piston as shown in the drawing below. The cylinder and the piston are adiabatically isolated.( no heat can escape or enter) Because of the gravitational field and the mass of the piston the gas will remain in the cylinder(in thermodynamic equllibrium). Let's say that the piston has mass m.

Now consider sticking on the piston a ball of mass M>m. Because of the weight of the ball the gas will contract (NOT QUASISTATIC), the piston going down. After this the gas will expand the piston going up, so on and so forth. Will the oscillations of the piston stop? (in other words , will the system ever reach thermodyamic equillibrium)

The interesting thing about this problem is that we can't apply the adiabatic process formula(because the process is not quasistatic) $$P\cdot V^{\gamma}=const$$ . Is sort of like free expansion, where we don't have a defined thermodynamic path in the PV plane.

What do you think?

I've been thinking a lot about this thermodynamics problem , hearing all sorts of opinions but never getting a full rigurous explanation. So we have a cylinder that is placed in vacuum. We insert in the cylinder a monoatomic ideal gas. The gas is trapped inside the cylinder with a piston as shown in the drawing below. The cylinder and the piston are adiabatically isolated.( no heat can escape or enter) Because of the gravitational field and the mass of the piston the gas will remain in the cylinder(in thermodynamic equllibrium). Let's say that the piston has mass m.

Now consider sticking on the piston a ball of mass M>m. Because of the weight of the ball the gas will contract (NOT QUASISTATIC), the piston going down. After this the gas will expand the piston going up, so on and so forth. Will the oscillations of the piston stop? (in other words , will the system ever reach thermodyamic equillibrium)

The interesting thing about this problem is that we can't apply the adiabatic process formula(because the process is not quasistatic) $$P\cdot V^{\gamma}=const$$ . Is sort of like free expansion, where we don't have a defined thermodynamic path in the PV plane.

What do you think?