- #1

zenterix

- 480

- 70

- TL;DR Summary

- How do we interpret the partial derivative of wire tension relative to temperature, holding wire length constant?

I have a question about a derivation I saw in the book "Heat and Thermodynamics" by Zemansky and Dittman.

A "sufficiently complete" thermodynamic description of a wire is given in terms of only three coordinates

1. tension in the wire, ##\zeta##

2. length of the wire, ##L##

3. absolute temperature, ##T##

What this means is that we have a simple thermodynamic system (defined generally as a system with three thermodynamic coordinates T, Y, Z, where T is temperature).

The book says

I was a little confused by the expression "as a rule" in the snippet above. What rule?

Now let's consider an infinitesimal change from one state of equilibrium to another.

$$dL=\left (\frac{\partial L}{\partial T}\right )_{\zeta} dT+\left (\frac{\partial T}{\partial \zeta}\right )_{T} d\zeta$$

My first question is about the assumption that we have a function ##L=L(\zeta, T)##. This is an equation of state (albeit, functionally unspecified of course).

Is the implicit equation of state the one mentioned in the snippet above that cannot be expressed by a simple equation?

There is a physical quantity called linear expansivity, defined as

$$\alpha=\frac{1}{L}\left (\frac{\partial L}{\partial T}\right )_{\zeta}$$

and another called isothermal Young's modulus, defined

$$Y=\frac{L}{A}\left (\frac{\partial\zeta}{\partial L}\right )_{T}$$

where ##A## denotes the cross section of the wire.

Now, ##\alpha## is usually positive for metals, and ##A## is always positive, according to the book. These are experimentally determined for different materials.

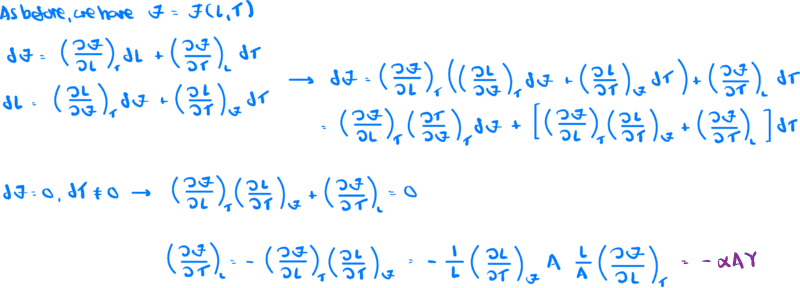

The derivations that follow are to obtain an expression for ##\left (\frac{\partial\zeta}{\partial T}\right )_{L}## in terms of the physical quantities above.

I will attach a screenshot of the detailed derivation, but the result is

$$\left (\frac{\partial\zeta}{\partial T}\right )_{L} = -\alpha AY$$

My second question is how to interpret this equation.

It seems to say that for an increase in temperature, keeping the length of the wire constant, the tension decreases. Is this true?

Is the point of this derivation to show that even without an explicit equation of state we can obtain useful rates of change like this?

It is not clear why the book mentioned that Hooke's law holds sometimes. Again, is it to show that even if we don't have something like Hooke's law we can make use of differential calculus to obtain useful results since we can measure the terms in the mathematical expressions we obtain?

How does one physically heat up a wire while keeping the length constant but the tension variable?

Finally, here is a screenshot of the derivation of the result shown above

A "sufficiently complete" thermodynamic description of a wire is given in terms of only three coordinates

1. tension in the wire, ##\zeta##

2. length of the wire, ##L##

3. absolute temperature, ##T##

What this means is that we have a simple thermodynamic system (defined generally as a system with three thermodynamic coordinates T, Y, Z, where T is temperature).

The book says

The states of thermodynamic equilibrium are connected by an equation of state that, as a rule, cannot be expressed by a simple equation.

For a wire at constant temperature within the limit of elasticity, however, Hooke's law holds; namely, for the tension ##\zeta## in a stretched wire.

$$\zeta=-k(L-L_0)$$

where ##k## is Hooke's constant and ##L_0## is the length at zero tension.

I was a little confused by the expression "as a rule" in the snippet above. What rule?

Now let's consider an infinitesimal change from one state of equilibrium to another.

$$dL=\left (\frac{\partial L}{\partial T}\right )_{\zeta} dT+\left (\frac{\partial T}{\partial \zeta}\right )_{T} d\zeta$$

My first question is about the assumption that we have a function ##L=L(\zeta, T)##. This is an equation of state (albeit, functionally unspecified of course).

Is the implicit equation of state the one mentioned in the snippet above that cannot be expressed by a simple equation?

There is a physical quantity called linear expansivity, defined as

$$\alpha=\frac{1}{L}\left (\frac{\partial L}{\partial T}\right )_{\zeta}$$

and another called isothermal Young's modulus, defined

$$Y=\frac{L}{A}\left (\frac{\partial\zeta}{\partial L}\right )_{T}$$

where ##A## denotes the cross section of the wire.

Now, ##\alpha## is usually positive for metals, and ##A## is always positive, according to the book. These are experimentally determined for different materials.

The derivations that follow are to obtain an expression for ##\left (\frac{\partial\zeta}{\partial T}\right )_{L}## in terms of the physical quantities above.

I will attach a screenshot of the detailed derivation, but the result is

$$\left (\frac{\partial\zeta}{\partial T}\right )_{L} = -\alpha AY$$

My second question is how to interpret this equation.

It seems to say that for an increase in temperature, keeping the length of the wire constant, the tension decreases. Is this true?

Is the point of this derivation to show that even without an explicit equation of state we can obtain useful rates of change like this?

It is not clear why the book mentioned that Hooke's law holds sometimes. Again, is it to show that even if we don't have something like Hooke's law we can make use of differential calculus to obtain useful results since we can measure the terms in the mathematical expressions we obtain?

How does one physically heat up a wire while keeping the length constant but the tension variable?

Finally, here is a screenshot of the derivation of the result shown above

Last edited: