benca

- 19

- 0

- Homework Statement

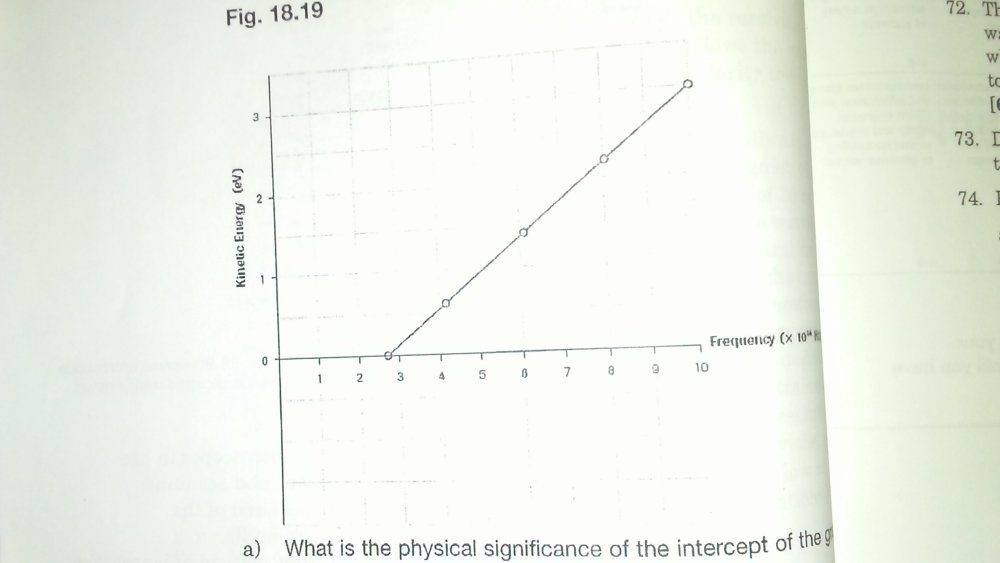

- Use the graph to determine Planck's constant.

- Relevant Equations

- E = hf

Ek = hf - W

h = Planck's constant

f = frequency

W = work function

Attempt:

I was thinking of finding the slope of the graph but I only know the values for x = 10, y = 3 and y = 0. And without the y-intercept, I don't know the work function and can't solve for h. If you can't see from the picture, the last co-ordinate is (10,3) and the x-axis is measured in f x 10^14 Hz

I'm not sure what options I have left if I don't know how to figure out the slope or work function.

I was thinking of finding the slope of the graph but I only know the values for x = 10, y = 3 and y = 0. And without the y-intercept, I don't know the work function and can't solve for h. If you can't see from the picture, the last co-ordinate is (10,3) and the x-axis is measured in f x 10^14 Hz

I'm not sure what options I have left if I don't know how to figure out the slope or work function.