Derivation of Gauss’s Law: Coulomb to Flux Explained

Gauss’s law was formulated by Carl Friedrich Gauss in 1835. It is one of the four Maxwell’s equations that form the basis of classical electrodynamics. Gauss’s law is important because it reveals a simple relation between a field and the distribution of charge.

In electrostatics, applying Gauss’s law often greatly simplifies the calculation of an electric field for symmetric charge distributions. Below we derive Gauss’s law for electrostatic fields by showing its relation to Coulomb’s law.

Table of Contents

Gauss’s Law Formalism

Gauss’s law can be expressed both in integral form and in differential form. The two forms are equivalent and are related by the divergence theorem.

Integral form: ∯S E·dA = Q/ε0

Differential form: ∇·E = ρ/ε0

Gauss’s law is essentially equivalent to Coulomb’s law. Any inverse-square law can be written in a form similar to Gauss’s law.

Qualitative Derivation

In physics, many complicated problems are solved by starting with simple cases and then extending to more general situations. We apply that approach here. We divide the derivation into three parts, each more general than the previous: (1) a point charge inside a spherical surface, (2) a point charge inside a non-spherical surface, and (3) an arbitrary charge distribution inside a closed surface.

Point Charge Inside a Spherical Surface

When a point charge q is placed at the center of an imaginary spherical surface (a Gaussian surface) of radius R, the magnitude of the electric field at every point on the surface is given by E = q / (4πε0 R2).

At every point on the surface the field is perpendicular to the surface and its magnitude is the same everywhere. Therefore the total electric flux ΦE through the spherical surface is the product of the field magnitude and the total surface area of the sphere:

ΦE = E A = (q / (4πε0 R2)) · (4πR2) = q / ε0

This result matches the integral form of Gauss’s law and demonstrates the equivalence with Coulomb’s law for this symmetric case.

Point Charge Inside a Non-spherical Surface

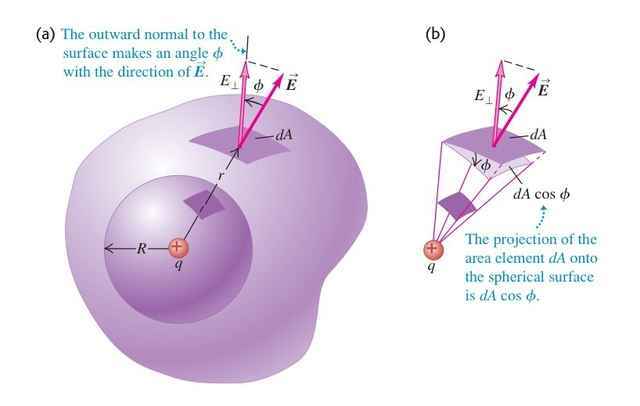

Next consider the same point charge q, but now enclose it with an arbitrary closed (non-spherical) surface. Choose the concentric spherical surface used previously as a reference and compare small corresponding area elements on the two surfaces.

Take a small area element dA on the irregular surface and project it radially onto the corresponding area element dA′ on the concentric sphere at the same distance from q (see diagram (a) and (b)). The area dA is related to the projected area dA′ by the angle φ between the local surface normal and the radial direction to the charge: the projected area on the sphere is foreshortened by cosφ, so dA′ = dA cosφ.

The flux through the small irregular area element is ΦdA = E⊥ dA = E (dA cosφ) = E dA′.

Integrating over the entire irregular surface therefore gives the same total flux as through the sphere at the same radius. From the spherical case we already have:

ΦE = ∮ E·dA = q / ε0

Thus Gauss’s law holds for a point charge enclosed by any closed surface in a static field.

General Form (Multiple Charges)

For multiple enclosed charges q1, q2, q3, … the resulting electric field at any point is the vector sum of the fields from each charge. Applying the same analysis to each charge and summing the contributions gives the total electric flux through a closed surface:

ΦE = ∮ E·dA = Qenc / ε0

Qenc = q1 + q2 + q3 + …

Therefore, the total electric flux through a closed surface equals the total charge enclosed divided by ε0.

Experimental Proof

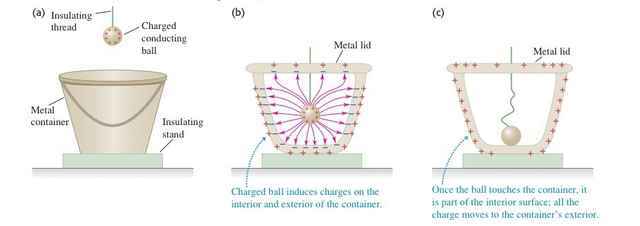

The famous Faraday ice-pail experiment provides an experimental confirmation of Gauss’s law. Because Gauss’s law is equivalent to Coulomb’s law, the ice-pail experiment also offers a precise demonstration of the inverse-square relationship for electrostatic forces; Coulomb’s original torsion-balance measurements were less accurate.

In the experiment a conducting container is mounted on an insulating stand and is initially uncharged. A charged metal ball is suspended from an insulating thread and lowered into the container, which is then closed with a lid. Charges are induced on the inner and outer walls of the container. If the ball is allowed to touch the inner surface, charge transfers so that the ball’s surface becomes part of the cavity surface. If Gauss’s law holds, the net charge on the cavity surface must be equal to the charge originally on the ball; removing the ball afterwards and measuring shows that the ball has lost its charge and the container retains the induced charge, consistent with Gauss’s law for static fields.

Summary

We derived Gauss’s law by starting from the simple, highly symmetric case (a point charge at the center of a sphere) and then extending the argument to irregular closed surfaces and to multiple charges. We also described experimental confirmation via the Faraday ice-pail experiment. The same stepwise analytical process is often used for other Maxwell equations (for example, Ampère’s law).

Note that this presentation proves Gauss’s law for charges inside a closed surface in electrostatics; we have not discussed the treatment of charges outside the surface here. Also, Gauss’s law is more general and applies to time-varying fields when combined with Maxwell’s other equations.

Reference

University Physics with Modern Physics

Currently a high school student, passionate about physics, especially areas of theoretical particle physics. Benefited a lot from study of physics MOOCs and great platforms like Physics Forums.

Does electricity have superimposed intelligence (wisdom)? Choosing pathway of least resistance? Might her decisions be better understood in viewing her as a simple relationship between field and wave distribution, for her period as a particle she is at rest as torsion field perpendicular to spinning black hole? As a wave seeking harmonic balance, adjustability …

Two thumbs up!

I am surprised you’re in high school. Nice. Congratulations.