Limits of Functions for Calculus: Definition & Examples

Table of Contents

What is a limit?

In mathematics, a limit describes the behavior of a function or sequence as its input approaches a particular value. Limits are a cornerstone of calculus and are used to define continuity, derivatives and integrals.

Key aspects of limits:

- Definition: The limit of a function or sequence as it approaches a specific value is written using “lim”. For example: [tex]\lim_{x \to a} f(x)[/tex].

- Approach: Limits consider what happens as the input gets arbitrarily close to a value a; they do not require the function to be defined at that exact point.

- Convergence: A limit exists if function values approach a single, well-defined value (which may be a real number or ±∞) as the input approaches a.

- Notation: We write [tex]\lim_{x \to a} f(x) = L[/tex] to mean that as x becomes arbitrarily close to a, f(x) becomes arbitrarily close to L.

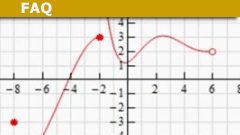

- One-sided limits: Behavior can differ when approaching from the right or left; these are written [tex]\lim_{x \to a^+} f(x)[/tex] (right-hand) and [tex]\lim_{x \to a^-} f(x)[/tex] (left-hand).

- Limit laws: Several algebraic rules (sum, product, quotient, constant factor) let you evaluate limits from simpler limits.

What is a function?

A function defines a specific relationship between two sets: the domain (inputs) and the codomain (possible outputs). Given an element of the domain, a function assigns exactly one element of the codomain.

Key characteristics of a function:

- Input–output relationship: Each input (independent variable) maps to a single output (dependent variable).

- Notation: Functions are commonly written as

f(x)ory = f(x). - Domain: The set of all input values for which the function is defined.

- Codomain and range: The codomain is the set of possible outputs; the range is the set of actual outputs produced from the domain.

- Uniqueness: A well-defined function never assigns multiple outputs to the same input.

- Graph: Functions can be represented visually; the graph shows the mapping from input to output.

- Examples: Linear, quadratic, trigonometric and exponential functions.

Definition of a limit of a function

Limits describe the “limiting value” a function seems to approach when its argument approaches some point. They are particularly useful where the function is not defined at that point or becomes very large.

We say that the argument “tends to” a value. For example:

[tex]\lim_{x \to c} f(x) = m[/tex]

This is read: “As x tends to c, f(x) tends to m.” This statement does not assert the value of f(c); it only describes the values of f(x) when x is very close to c.

If f is defined and continuous at c, then

[tex]\lim_{x \to c} f(x) = f(c)[/tex]

Limit laws (identities)

Standard limit identities that hold when the individual limits exist:

[tex]\lim_{x \to c} \bigl(f(x) + g(x)\bigr) = \lim_{x \to c} f(x) + \lim_{x \to c} g(x)[/tex]

[tex]\lim_{x \to c} \bigl(f(x)\cdot g(x)\bigr) = \bigl(\lim_{x \to c} f(x)\bigr)\cdot\bigl(\lim_{x \to c} g(x)\bigr)[/tex]

[tex]\lim_{x \to c} \frac{f(x)}{g(x)} = \frac{\lim_{x \to c} f(x)}{\lim_{x \to c} g(x)} \quad \text{(when } \lim_{x\to c} g(x)\ne 0\text{)}[/tex]

[tex]\lim_{x \to c} \bigl(\lambda\, f(x)\bigr) = \lambda\,\lim_{x \to c} f(x)[/tex]

Informal examples and extended explanation

1. Simplifying removable discontinuities (informal)

Let

[tex]f(x) = \frac{x^2 – 4}{x – 2}[/tex]

Algebraically this simplifies to

[tex]f(x) = \frac{(x – 2)(x + 2)}{x – 2} = x + 2, \quad x\ne 2[/tex]

Because cancellation removes the factor x-2, f is equal to x + 2 for all x ≠ 2. At x = 2 the original expression is undefined (0/0 is indeterminate), but values of f(x) near x = 2 approach 4. So

[tex]\lim_{x \to 2} f(x) = 4[/tex]

Since f(2) does not exist, [tex]\lim_{x \to 2} f(x) \ne f(2)[/tex] and f is not continuous at 2. If we instead define a function g by setting g(2)=4, then g would be continuous at 2.

2. Tending to infinity

Example: [tex]f(x) = \frac{1}{x}[/tex]. As x approaches 0, |f(x)| grows without bound. The two-sided limit does not exist, but the one-sided limits are:

[tex]\lim_{x \to 0^+} \frac{1}{x} = +\infty \quad\text{and}\quad \lim_{x \to 0^-} \frac{1}{x} = -\infty[/tex]

3. Right-hand and left-hand limits

Approach a value c from the right (x > c) or from the left (x < c). Write x = c + h with h → 0 to approach from the right, or x = c − h with h → 0 to approach from the left.

Right-hand limit (RHL): [tex]\lim_{x \to c^+} f(x) = \lim_{h \to 0^+} f(c + h)[/tex]

Left-hand limit (LHL): [tex]\lim_{x \to c^-} f(x) = \lim_{h \to 0^+} f(c – h)[/tex]

For a function to be continuous at c, both one-sided limits must exist and be equal to f(c).

4. Common standard limits (reference)

Useful limits often used in computations:

- [tex]\lim_{x \to c} x = c[/tex]

- [tex]\lim_{x \to 0^+} \frac{1}{x} = +\infty \quad\text{(two-sided limit does not exist)}

- [tex]\lim_{x \to \infty} x = \infty[/tex]

- [tex]\lim_{x \to 0} \frac{\sin x}{x} = 1[/tex]

- [tex]\lim_{x \to 0} \frac{\tan x}{x} = 1[/tex]

- [tex]\lim_{x \to 0} \frac{1 – \cos x}{x} = 0[/tex]

- [tex]\lim_{x \to a} \frac{x^n – a^n}{x – a} = n a^{\,n-1}[/tex]

- [tex]\lim_{x \to a} \frac{\sin(x-a)}{x-a} = 1[/tex]

- [tex]\lim_{x \to 0} \frac{\log_e(1 + x)}{x} = 1[/tex]

- [tex]\lim_{x \to 0} \frac{a^x – 1}{x} = \log_e a[/tex]

- [tex]\lim_{x \to 0} \frac{e^x – 1}{x} = 1[/tex]

This discussion treats pointwise limits of functions. Do not confuse these with limits of sequences of functions or other types of functional limits considered in functional analysis (see references for more on that topic).

I have a BS in Information Sciences from UW-Milwaukee. I’ve helped manage Physics Forums for over 22 years. I enjoy learning and discussing new scientific developments. STEM communication and policy are big interests as well. Currently a Sr. SEO Specialist at Shopify and writer at importsem.com

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!