Answering Mermin’s Challenge with the Relativity Principle

Note: This Insight was previously titled, “Answering Mermin’s Challenge with Wilczek’s Challenge.” While that version of this Insight did not involve any particular interpretation of quantum mechanics, it did involve the block universe interpretation of special relativity. I have updated this Insight to remove the block universe interpretation, so that it now answers Mermin’s challenge in “principle” fashion alone, as in this Insight.

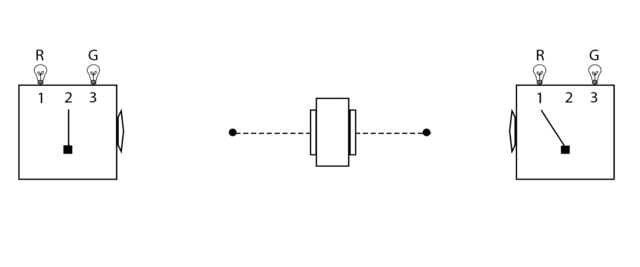

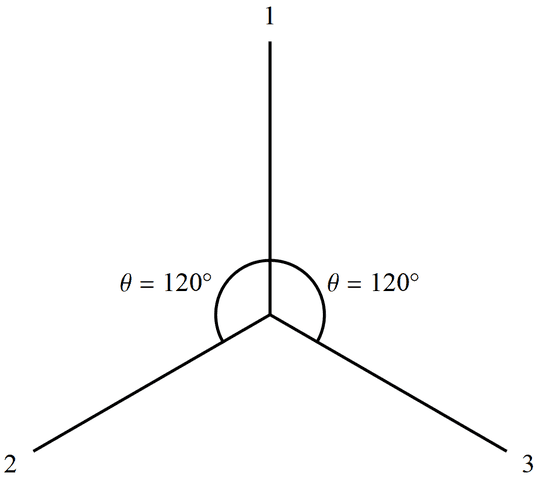

Nearly four decades ago, Mermin revealed the conundrum of quantum entanglement for a general audience [1] using his “simple device,” which I will refer to as the “Mermin device” (Figure 1). To understand the conundrum of the device required no knowledge of physics, just some simple probability theory, which made the presentation all the more remarkable. Concerning this paper Feynman wrote to Mermin, “One of the most beautiful papers in physics that I know of is yours in the American Journal of Physics” [2, p. 366-7]. In subsequent publications, he “revisited” [3] and “refined” [4] the mystery of quantum entanglement with similarly simple devices. In this Insight, I will focus on the original Mermin device as it relates to the mystery of entanglement via the Bell spin states.

Figure 1. The Mermin Device

The Mermin device functions according to two facts that are seemingly contradictory, thus the mystery. Mermin simply supplies these facts and shows the contradiction, which the “general reader” can easily understand. He then challenges the “physicist reader” to resolve the mystery in an equally accessible fashion for the “general reader.” Here is how the Mermin device works.

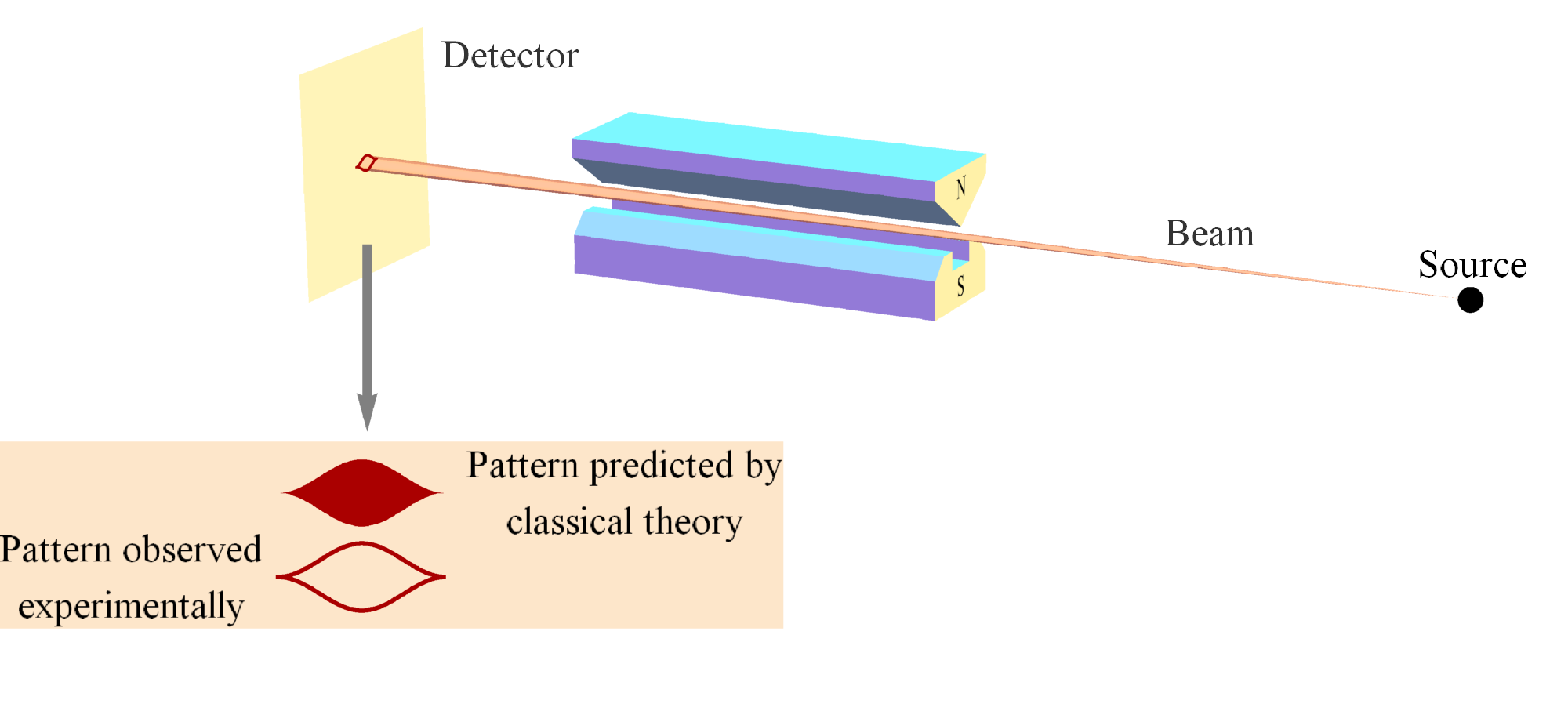

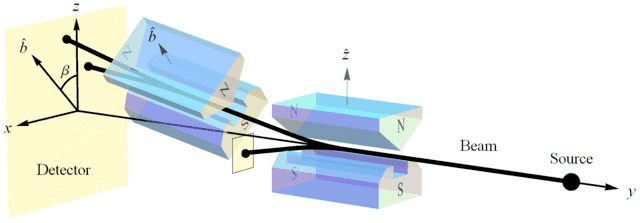

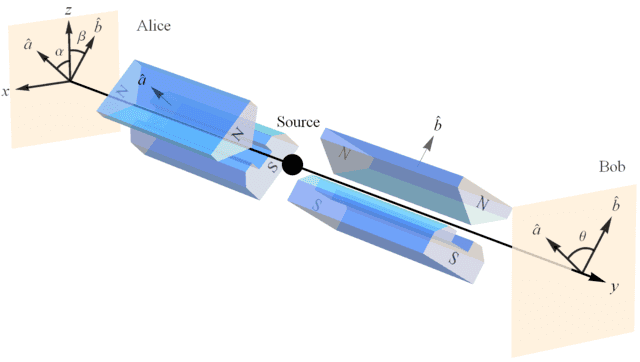

The Mermin device is based on the measurement of spin angular momentum (Figure 2). The spin measurements are carried out with Stern-Gerlach (SG) magnets and detectors (Figure 3). The Mermin device contains a source (middle box in Figure 1) that emits a pair of spin-entangled particles towards two detectors (boxes on the left and right in Figure 1) in each trial of the experiment. The settings (1, 2, or 3) on the left and right detectors are controlled randomly by Alice and Bob, respectively, and each measurement at each detector produces either a result of R or G. The following two facts obtain:

- When Alice and Bob’s settings are the same in a given trial (“case (a)”), their outcomes are always the same, ##\frac{1}{2}## of the time RR (Alice’s outcome is R and Bob’s outcome is R) and ##\frac{1}{2}## of the time GG (Alice’s outcome is G and Bob’s outcome is G).

- When Alice and Bob’s settings are different (“case (b)”), the outcomes are the same ##\frac{1}{4}## of the time, ##\frac{1}{8}## RR and ##\frac{1}{8}## GG.

The two possible Mermin device outcomes R and G represent two possible spin measurement outcomes “up” and “down,” respectively (Figure 2), and the three possible Mermin device settings represent three different orientations of the SG magnets (Figures 3 & 4).

Figure 2. A pair of Stern-Gerlach (SG) magnets showing the two possible outcomes, up (##+\frac{\hbar}{2}##) and down (##-\frac{\hbar}{2}##) or ##+1## and ##-1##, for short. The important point to note here is that the classical analysis predicts all possible deflections, not just the two that are observed. This difference uniquely distinguishes the quantum joint distribution from the classical joint distribution for spin entangled pairs [5].

Figure 3. Alice and Bob making spin measurements on a pair of spin-entangled particles with their SG magnets and detectors. In this particular case, the plane of conserved spin angular momentum is the xz plane.

Figure 4. Three orientations of SG magnets in the plane of symmetry for Alice and Bob’s spin measurements corresponding to the three settings on the Mermin device.

Mermin writes, “Why do the detectors always flash the same colors when the switches are in the same positions? Since the two detectors are unconnected there is no way for one to ‘know’ that the switch on the other is set in the same position as its own.” This leads him to introduce “instruction sets” to account for the behavior of the device when the detectors have the same settings. He writes, “It cannot be proved that there is no other way, but I challenge the reader to suggest any.” Now look at all trials when Alice’s particle has instruction set RRG and Bob’s has instruction set RRG, for example.

That means Alice and Bob’s outcomes in setting 1 will both be R, in setting 2 they will both be R, and in setting 3 they will both be G. That is, the particles will produce an RR result when Alice and Bob both choose setting 1 (referred to as “11”), an RR result when both choose setting 2 (referred to as “22”), and a GG result when both choose setting 3 (referred to as “33”). That is how instruction sets guarantee Fact 1. For different settings, Alice and Bob will obtain the same outcomes when Alice chooses setting 1 and Bob chooses setting 2 (referred to as “12”), which gives an RR outcome. And, they will obtain the same outcomes when Alice chooses setting 2 and Bob chooses setting 1 (referred to as “21”), which also gives an RR outcome. That means we have the same outcomes for different settings in 2 of the 6 possible case (b) situations, i.e., in ##\frac{1}{3}## of case (b) trials for this instruction set. This ##\frac{1}{3}## ratio holds for any instruction set with two R(G) and one G(R).

The only other possible instruction sets are RRR or GGG where Alice and Bob’s outcomes will agree in ##\frac{9}{9}## of all trials. Thus, the “Bell inequality” for the Mermin device says that instruction sets must produce the same outcomes in more than ##\frac{1}{3}## of all case (b) trials. But, Fact 2 for the Mermin device says you only get the same outcomes in ##\frac{1}{4}## of all case (b) trials, thereby violating the Bell inequality. Thus, the conundrum of Mermin’s device is that the instruction sets needed for Fact 1 fail to yield the proper outcomes for Fact 2.

Concerning his device Mermin wrote, “Although this device has not been built, there is no reason in principle why it could not be, and probably no insurmountable practical difficulties.” Sure enough, the experimental confirmation of the violation of Bell’s inequality per quantum entanglement is so common that it can now be carried out in the undergraduate physics laboratory [6]. Thus, there is no disputing that the conundrum of the Mermin device has been experimentally well verified, vindicating its prediction by quantum mechanics.

While the conundrum of the Mermin device is now a well-established fact, Mermin’s “challenging exercise to the physicist reader to translate the elementary quantum-mechanical reconciliation of cases (a) and (b) into terms meaningful to a general reader struggling with the dilemma raised by the device” arguably remains unanswered. To answer this challenge, it is generally acknowledged that one needs a compelling causal mechanism or a compelling physical principle by which the conundrum of the Mermin device is resolved. Such a model needs to do more than the “Copenhagen interpretation” [7], which Mermin characterized as “shut up and calculate” [8]. In other words, while the formalism of quantum mechanics accurately predicts the conundrum, quantum mechanics does not provide a model of physical reality or underlying physical principle to resolve the conundrum. While there are many interpretations of quantum mechanics, even one published by Mermin [9], there is no consensus among physicists on any given interpretation.

Rather than offer yet another uncompelling interpretation of quantum mechanics, I will share and expand on an underlying physical principle [10,11] that explains the quantum correlations responsible for the conundrum of the Mermin device. In other words, I will provide a “principle account” of quantum entanglement. Here I’m making specific reference to Einstein’s notion of a “principle theory” as explained in this Insight. While this explanation, conservation per no preferred reference frame (NPRF), may not be “in terms meaningful to a general reader,” it is pretty close. That is, all one needs to appreciate the explanation is a course in introductory physics, which probably represents the “general reader” interested in this topic.

That quantum mechanics accurately predicts the observed phenomenon without spelling out any means a la “instruction sets” for how it works prompted Smolin to write [12, p. xvii]:

I hope to convince you that the conceptual problems and raging disagreements that have bedeviled quantum mechanics since its inception are unsolved and unsolvable, for the simple reason that the theory is wrong. It is highly successful, but incomplete.

Of course, this is precisely the complaint leveled by Einstein, Podolsky and Rosen (EPR) in their famous 1935 paper [13], “Can Quantum-Mechanical Description of Physical Reality Be Considered Complete?” Contrary to this belief, I will show that quantum mechanics is actually as complete as possible, given Einstein’s own relativity principle (NPRF). Indeed, Einstein missed a chance to rid us of his “spooky actions at a distance.” All he would have had to do is extend his relativity principle to include the measurement of Planck’s constant h, just as he had done by extending the relativity principle from mechanics to include the measurement of the speed of light c per electromagnetism.

That is, the relativity principle (NPRF) entails the light postulate of special relativity, i.e., that everyone measure the same speed of light c, regardless of their motion relative to the source. If there was only one reference frame for a source in which the speed of light equalled the prediction from Maxwell’s equations (##c = \frac{1}{\sqrt{\mu_o\epsilon_o}}##), then that would certainly constitute a preferred reference frame. The light postulate then leads to time dilation, length contraction, and the relativity of simultaneity per the Lorentz transformations of special relativity. Indeed, this is the way special relativity is introduced by Serway & Jewett [14] and Knight [15] for introductory physics students. Let me show you how further extending NPRF to the measurement of Planck’s constant h leads to quantum entanglement per the qubit Hilbert space structure (probability structure) of quantum mechanics.

Figure 5. In this set up, the first SG magnets (oriented at ##\hat{z}##) are being used to produce an initial state ##|\psi\rangle = |u\rangle## for measurement by the second SG magnets (oriented at ##\hat{b}##).

As Weinberg points out [16], measuring an electron’s spin via SG magnets constitutes the measurement of “a universal constant of nature, Planck’s constant” (Figure 2). So if NPRF applies equally here, then everyone must measure the same value for Planck’s constant h, regardless of their SG magnet orientations relative to the source, which like the light postulate is an “empirically discovered” fact. By “relative to the source,” I might mean relative “to the vertical in the plane perpendicular to the line of flight of the particles” [1], ##\hat{z}## in Figure 5 for example. Here the possible spin outcomes ##\pm\frac{\hbar}{2}## represent a fundamental (indivisible) unit of information per Dakic & Brukner’s first axiom in their information-theoretic reconstruction of quantum theory [17], “An elementary system has the information carrying capacity of at most one bit.” Thus, different SG magnet orientations relative to the source constitute different “reference frames” in quantum mechanics just as different velocities relative to the source constitute different “reference frames” in special relativity.

To make the analogy more explicit, one could have employed NPRF to predict the light postulate as soon as Maxwell showed electromagnetic radiation propagates at ##c = \frac{1}{\sqrt{\mu_o\epsilon_o}}##. All they would have had to do is extend the relativity principle from mechanics to electromagnetism. However, given the understanding of waves at the time, everyone rather began searching for a propagation medium, i.e., the luminiferous ether. Likewise, one could have employed NPRF to predict spin angular momentum as soon as Planck published his wavelength distribution function for blackbody radiation. All they would have had to do is extend the relativity principle from mechanics and electromagnetism to quantum physics. However, given the understanding of angular momentum and magnetic moments at the time, Stern & Gerlach rather expected to see their silver atoms deflected in a continuum distribution after passing through their magnets (Figure 2). In other words, they discovered spin angular momentum when they were simply looking for angular momentum. But, had they noticed that their measurement constituted a measurement of Planck’s constant (with its dimension of angular momentum), they could have employed NPRF to predict the spin outcome with its qubit Hilbert space structure (Figures 2 & 5) and its ineluctably probabilistic nature, as I will now explain.

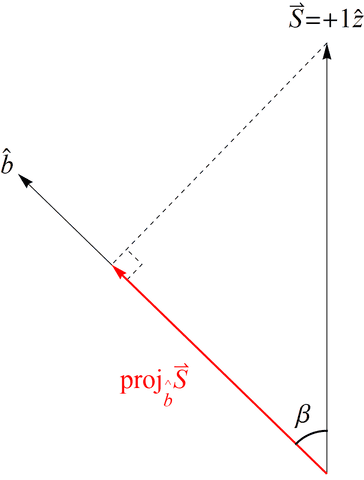

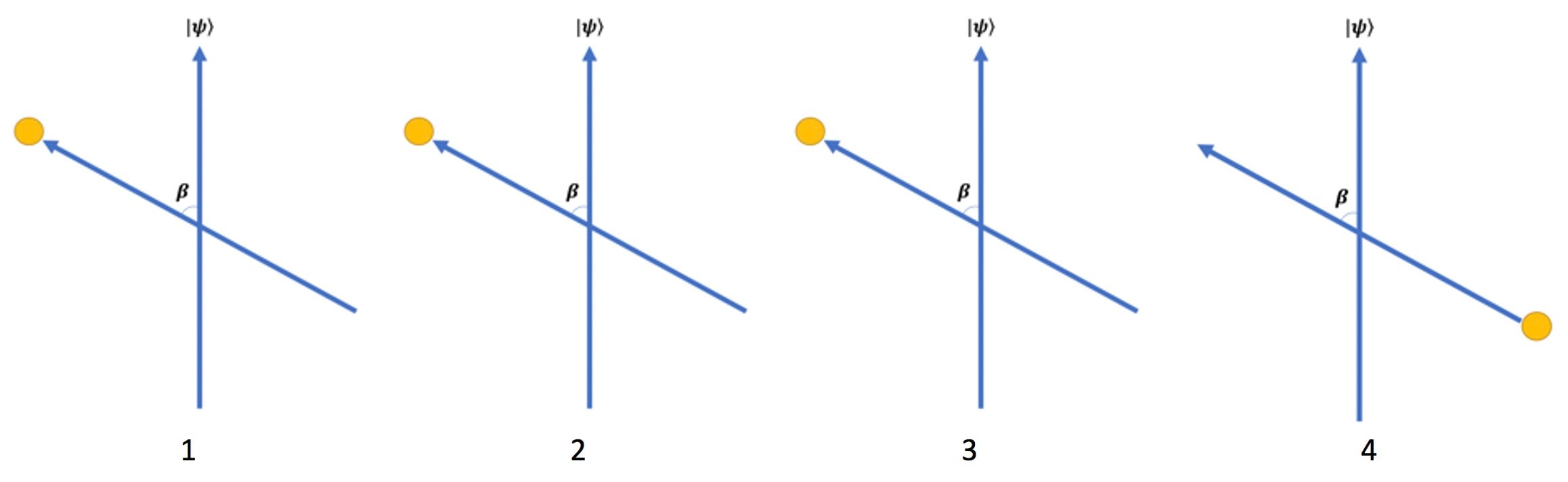

If we create a preparation state oriented along the positive ##z## axis as in Figure 5, i.e., ##|\psi\rangle = |u\rangle## in the Dirac notation [18], our spin angular momentum is ##\vec{S} = +1\hat{z}## (in units of ##\frac{\hbar}{2} = 1##). Now proceed to make a measurement with the SG magnets oriented at ##\hat{b}## making an angle ##\beta## with respect to ##\hat{z}## (Figure 5). According to classical physics, we expect to measure ##\vec{S}\cdot\hat{b} = \cos{(\beta)}## (Figure 6), but we cannot measure anything other than ##\pm 1## due to NPRF (contra the prediction by classical physics), so we see that NPRF answers Wheeler’s “Really Big Question,” “Why the quantum?” in “one clear, simple sentence” to convey “the central point and its necessity in the construction of the world” [19,20].

Figure 6. The spin angular momentum of Bob’s particle ##\vec{S}## projected along his measurement direction ##\hat{b}##. This does not happen with spin angular momentum due to NPRF.

As a consequence, we can only recover ##\cos{(\beta)}## on average (Figure 7), i.e., NPRF dictates “average-only” projection

\begin{equation}

(+1) P(+1 \mid \beta) + (-1) P(-1 \mid \beta) = \cos (\beta) \label{AvgProjection}

\end{equation}

Solving simultaneously with our normalization condition ##P(+1 \mid \beta) + P(-1 \mid \beta) = 1##, we find that

\begin{equation}

P(+1 \mid \beta) = \mbox{cos}^2 \left(\frac{\beta}{2} \right) \label{UPprobability}

\end{equation}

and

\begin{equation}

P(-1 \mid \beta) = \mbox{sin}^2 \left(\frac{\beta}{2} \right) \label{DOWNprobability}

\end{equation}

Figure 7. An ensemble of 4 SG measurement trials with ##\beta = 60^{\circ}##. The tilted blue arrow depicts an SG measurement orientation and the vertical arrow represents our preparation state ##|\psi\rangle = |u\rangle## (Figure 5). The yellow dots represent the two possible measurement outcomes for each trial, up (located at arrow tip) or down (located at bottom of arrow). The expected projection result of ##\cos{(\beta)}## cannot be realized because the measurement outcomes are binary (quantum) with values of ##+1## (up) or ##-1## (down) per NPRF. Thus, we have “average-only” projection for all 4 trials (three up outcomes and one down outcome for ##\beta = 60^\circ## average to ##\cos{(60^\circ)}=\frac{1}{2}##).

This explains the ineluctably probabilistic nature of QM, as pointed out by Mermin [21]:

Quantum mechanics is, after all, the first physical theory in which probability is explicitly not a way of dealing with ignorance of the precise values of existing quantities.

That is, quantum mechanics is as complete as possible, given the relativity principle. Of course, these “average-only” results due to “no fractional outcomes per NPRF” hold precisely for the qubit Hilbert space structure of quantum mechanics [11]. Thus, we see that NPRF provides a principle explanation of the kinematic/probability structure of quantum mechanics, just as it provides a principle explanation of the kinematic/Minkowski spacetime structure of special relativity. In fact, this follows from Information Invariance & Continuity at the basis of axiomatic reconstructions of QM per information-theoretic principles (see No Preferred Reference Frame at the Foundation of Quantum Mechanics). Now let’s expand this idea to the situation when we have two entangled particles, as in the Mermin device. The concept we need to understand now is the “correlation function.”

The correlation function between two outcomes over many trials is the average of the two values multiplied together. In this case, there are only two possible outcomes for any setting, +1 (up or R) or –1 (down or G), so the largest average possible is +1 (total correlation, RR or GG, as when the settings are the same) and the smallest average possible is –1 (total anti-correlation, RG or GR). One way to write the equation for the correlation function is

\begin{equation}\langle \alpha,\beta \rangle = \sum (i \cdot j) \cdot p(i,j \mid \alpha,\beta) \label{average}\end{equation}

where ##p(i,j \mid \alpha,\beta)## is the probability that Alice measures ##i## and Bob measures ##j## when Alice’s SG magnet is at angle ##\alpha## and Bob’s SG magnet is at angle ##\beta##, and ##(i \cdot j)## is just the product of the outcomes ##i## and ##j##. The correlation function for instruction sets for case (a) is the same as that of the Mermin device for case (a), i.e., they’re both 1. Thus, we must explore the difference between the correlation function for instruction sets and the Mermin device for case (b).

To get the correlation function for instruction sets for different settings, we need the probabilities of measuring the same outcomes and different outcomes for case (b), so we can use Eq. (\ref{average}). We saw that when we had two R(G) and one G(R), the probability of getting the same outcomes for different settings was ##\frac{1}{3}## (this would break down to ##\frac{1}{6}## for each of RR and GG overall). Thus, the probability of getting different outcomes would be ##\frac{2}{3}## for these types of instruction sets (##\frac{1}{3}## for each of RG and GR). That gives a correlation function of

\begin{equation}\langle \alpha,\beta \rangle = \left(+1\right)\left(+1\right)\left(\frac{1}{6}\right) + \left(-1\right)\left(-1\right)\left(\frac{1}{6}\right) + \left(+1\right)\left(-1\right)\left(\frac{2}{6}\right) + \left(-1\right)\left(+1\right)\left(\frac{2}{6}\right)= -\frac{1}{3}

\end{equation}

For the other type of instruction sets, RRR and GGG, we would have a correlation function of ##+1## for different settings, so overall the correlation function for instruction sets for different settings has to be larger than ##-\frac{1}{3}##. In fact, if all eight possible instruction sets are produced with equal frequency, then for any given pair of case (b) settings, e.g., 12 or 13 or 23, you will obtain RR, GG, RG, and GR in equal numbers giving a correlation function of zero. That means the results are uncorrelated as one would expect given that all possible instruction sets are produced randomly, i.e., with equal frequency. From this we would typically infer that there is nothing that needs to be explained.

Fact 2 for the Mermin device says the probability of getting the same results (RR or GG) for different settings is ##\frac{1}{4}## (##\frac{1}{8}## for each of RR and GG). Thus, the probability of getting different outcomes for case (b) must be ##\frac{3}{4}## (##\frac{3}{8}## for each of RG and GR). That gives a correlation function of

\begin{equation}\langle \alpha,\beta \rangle = \left(+1\right)\left(+1\right)\left(\frac{1}{8}\right) + \left(-1\right)\left(-1\right)\left(\frac{1}{8}\right) + \left(+1\right)\left(-1\right)\left(\frac{3}{8}\right) + \left(-1\right)\left(+1\right)\left(\frac{3}{8}\right)= -\frac{1}{2}

\end{equation}

That means the Mermin device is more strongly anti-correlated for different settings than instruction sets. Indeed, if all possible instruction sets are produced with equal frequency, the Mermin device evidences something to explain (anti-correlated results) where instruction sets suggest there is nothing to explain (uncorrelated results). Thus, quantum mechanics predicts and we observe anti-correlated outcomes for different settings in need of explanation while its classical counterpart suggests there is nothing in need of explanation at all. Mermin’s challenge then amounts to explaining why that is true for the “general reader.”

At this point read my Insight Exploring Bell States and Conservation of Spin Angular Momentum.

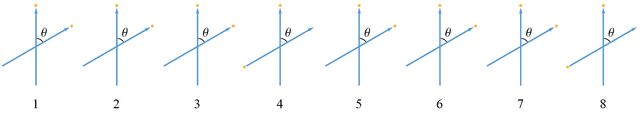

Now you understand how the correlation function for the Bell spin states results from “average-only” conservation (as a mathematical fact, Figure 8) resulting from the fact that Alice and Bob both always measure ##\pm 1 \left(\frac{\hbar}{2}\right)## (quantum), never a fraction of that amount (classical), as shown in Figure 2 (empirical fact).

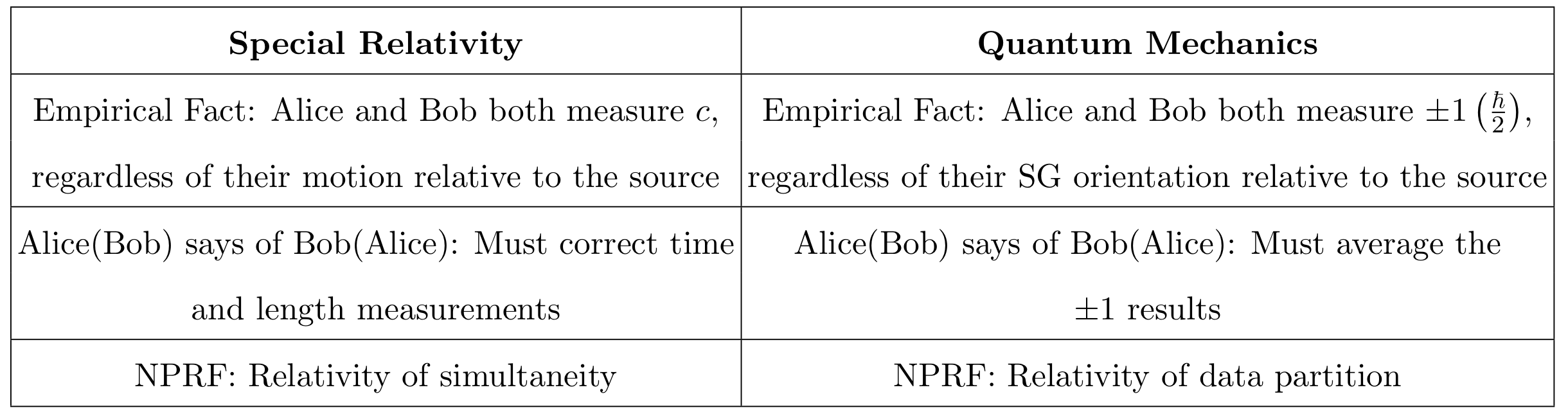

There are two important points to be made here. First, NPRF is just the statement of an “empirically discovered” fact, i.e., Alice and Bob both always measure ##\pm 1##. Second, it is simply a mathematical fact that the “average-only” conservation yields the quantum correlation functions. In other words, to paraphrase Einstein, “we have an empirically discovered principle that gives rise to mathematically formulated criteria which the separate processes or the theoretical representations of them have to satisfy.” That is why this principle account of quantum entanglement provides “logical perfection and security of the foundations.” Thus, we see how quantum entanglement follows from NPRF applied to the measurement of h in precisely the same manner that time dilation and length contraction follow from NPRF applied to the measurement of c. And, just like in special relativity, Bob could partition the data according to his equivalence relation (per his reference frame) and claim that it is Alice who must average her results (obtained in her reference frame) to conserve spin angular momentum (Figure 9).

Figure 8. An ensemble of 8 experimental trials for the Bell spin states showing Bob’s outcomes corresponding to Alice‘s ##+1## outcomes when ##\theta = 60^\circ##. Angular momentum is not conserved in any given trial, because there are two different measurements being made, i.e., outcomes are in two different reference frames, but it is conserved on average for all 8 trials (six up outcomes and two down outcomes average to ##\cos{60^\circ}=\frac{1}{2}##). It is impossible for angular momentum to be conserved explicitly in each trial since the measurement outcomes are binary (quantum) with values of ##+1## (up) or ##-1## (down) per NPRF. The conservation principle at work here assumes Alice and Bob’s measured values of spin angular momentum are not mere components of some hidden angular momentum with variable magnitude. That is, the measured values of angular momentum are the angular momenta contributing to this conservation, as I explained in my Insight Bell States and Conservation of Spin Angular Momentum.

Figure 9. Comparing special relativity with quantum mechanics according to no preferred reference frame (NPRF).

Of course, all of this does not provide any relief for those who still require explanation via “constructive efforts.” As Lorentz complained [22]:

Einstein simply postulates what we have deduced, with some difficulty and not altogether satisfactorily, from the fundamental equations of the electromagnetic field.

And, Albert Michelson said [23]:

It must be admitted, these experiments are not sufficient to justify the hypothesis of an ether. But then, how can the negative result be explained?

In other words, neither was convinced that NPRF was sufficient to explain time dilation and length contraction. Apparently for them, such a principle must be accounted for by some causal mechanism, e.g., the luminiferous ether. Likewise, if one requires “constructive efforts” to account for “conservation per NPRF” responsible for “average-only” conservation, then they will certainly want to continue the search for a causal mechanism responsible for quantum entanglement.

But after 115 years, physicists have largely abandoned theories of the luminiferous ether, having grown comfortable with the longstanding and empirically sound light postulate based on NPRF. Even Lorentz seemed to acknowledge the value of this principle explanation when he wrote [22]:

By doing so, [Einstein] may certainly take credit for making us see in the negative result of experiments like those of Michelson, Rayleigh, and Brace, not a fortuitous compensation of opposing effects but the manifestation of a general and fundamental principle.

Therefore, 85 years after publication of the EPR paper, perhaps we should consider the possibility that quantum entanglement will likewise ultimately yield to principle explanation. After all, we now know that our time-honored relativity principle is precisely the principle that resolves the mystery of “spooky actions at a distance.” As John Bell said in 1993 [24, p. 85]:

I think the problems and puzzles we are dealing with here will be cleared up, and … our descendants will look back on us with the same kind of superiority as we now are tempted to feel when we look at people in the late nineteenth century who worried about the ether. And Michelson-Morley .., the puzzles seemed insoluble to them. And came Einstein in nineteen five, and now every schoolboy learns it and feels .. superior to those old guys. Now, it’s my feeling that all this action at a distance and no action at a distance business will go the same way. But someone will come up with the answer, with a reasonable way of looking at these things. If we are lucky it will be to some big new development like the theory of relativity.

Perhaps causal accounts of quantum entanglement are destined to share the same fate as theories of the luminiferous ether. Regardless, we have certainly answered Mermin’s challenge, since conservation per NPRF is very accessible to the “general reader.”

References

- Mermin, N.D.: Bringing home the atomic world: Quantum mysteries for anybody. American Journal of Physics 49, 940-943 (1981).

- Feynman, M.: Perfectly Reasonable Deviations from the Beaten Track. Basic Books, New York (2005).

- Mermin, N.D.: Quantum mysteries revisited. American Journal of Physics 58, 731-734 (Aug 1990).

- Mermin, N.D.: Quantum mysteries refined. American Journal of Physics 62, 880-887 (Aug 1994).

- Garg, A., and Mermin, N.D.: Bell Inequalities with a Range of Violation that Does Not Diminish as the Spin Becomes Arbitrarily Large. Physical Review Letters 49(13), 901–904 (1982).

- Dehlinger, D., and Mitchell, M.W.: Entangled photons, nonlocality, and Bell inequalities in the undergraduate laboratory. American Journal of Physics 70(9), 903–910 (2002).

- Becker, A.: What is Real? The Unfinished Quest for the Meaning of Quantum Physics. Basic Books, New York (2018).

- Mermin, N.D.: Could Feynman Have Said This? Physics Today 57(5), 10 (Apr 2004).

- Mermin, N.D.: What is quantum mechanics trying to tell us? American Journal of Physics 66(9), 753-767 (1998).

- Stuckey, W.M., Silberstein, M., and McDevitt, T., and Le, T.D.: Answering Mermin’s challenge with conservation per no preferred reference frame. Scientific Reports 10, 15771 (2020).

- Silberstein, M., Stuckey, W.M., and McDevitt, T.: Beyond Causal Explanation: Einstein’s Principle Not Reichenbach’s. Entropy 23(1), 114 (2021).

- Smolin, L.: Einstein’s Unfinished Revolution: The Search for What Lies Beyond the Quantum. Penguin Press, New York (2019).

- Einstein, A., Podolsky, B., and Rosen, N.: Can Quantum-Mechanical Description of Physical Reality Be Considered Complete? Physical Review 47(10), 777–780 (1935).

- Serway, R., and Jewett, J.: Physics for Scientists and Engineers with Modern Physics. Cengage, Boston (2019).

- Knight, R.: Physics for Scientists and Engineers with Modern Physics. Pearson, San Francisco (2008).

- Weinberg, S.: The Trouble with Quantum Mechanics. (2017).

- Dakic, B., and Brukner, C.: Quantum Theory and Beyond: Is Entanglement Special? In: Deep Beauty: Understanding the Quantum World through Mathematical Innovation. Halvorson, H. (ed.). Cambridge University Press, New York (2009), 365–393.

- Ross, R.: Computer simulation of Mermin’s quantum device. American Journal of Physics 88(6), 483–489 (2020).

- Barrow, J.D., Davies, P.C.W., and Harper, C.: Science and Ultimate Reality: Quantum Theory, Cosmology, and Complexity. Cambridge University Press, New York (2004).

- Wheeler, J.: How Come the Quantum? Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences: New Techniques and Ideas in Quantum Measurement Theory 480(1), 304–316 (1986).

- Mermin, N.D.: Making better sense of quantum mechanics. Reports on Progress in Physics 82, 012002 (2019).

- Lorentz, H.A.: The Theory of Electrons and Its Applications to the Phenomena of Light and Radiant Heat. G.E. Stechert and Co., New York (1916).

- A. Michelson quote from 1931 in Episode 41 “The Michelson-Morley Experiment” in the series “The Mechanical Universe,” written by Don Bane (1985).

- Bell, J.S.: Indeterminism and Nonlocality. In: Mathematical Undecidability, Quantum Nonlocality and the Question of the Existence of God. Driessen, A., and Suarez, A. (eds.). Springer, Netherlands (1997), 78–89.

PhD in general relativity (1987), researching foundations of physics since 1994. Coauthor of “Beyond the Dynamical Universe” (Oxford UP, 2018).

There are any number of reasons you might want to use ##y = 0##, but you have to come up the reason to do so. You don’t use the math to dictate the use of ##y = 0##. What if I want to use the math for throwing a ball? I don’t use ##y = 0## because I believe it is not possible to find empirical verification of that fact. Again, the empirically verifiable physics drives what you use of the math, not the converse. So, again, what is your prediction requiring I keep ##a = 0## with ##\rho = \infty##? Produce that prediction and its empirical verification and we’ll know we have to keep that region.

I am missing something very basic here. Take for example ##y''=2## on the interval ##[0,2]## with ##y(1)=1## and ##y(2)=4##. The only solution is ##y(x)=x^2##. How do you make ##y(0)## not equal to zero?

Look again at the partial parabola for the trajectory of a ball with ##y(0) = 3##. We don’t include the mathematical extension into negative times demanding therefore we must include ##y = 0##. Why? Because we don’t believe there can be any empirical evidence of that fact. So, in adynamical thinking the onus is on you to produce a prediction with empirical evidence showing you need to include ##a = 0## with ##\rho = \infty##. We can then do the experiment and see if your prediction is verified. If so, according to your theory, we need to include that region. There is no reason to include mathematics in physics unless that mathematics leads to empirically verifiable predictions. So, what is your prediction?

That doesn't explain why you would cut off a solution of the EFE short of its maximal analytic extension.

Again, you have to do this if you want your model to make testable predictions about observations that haven't been made yet.

Also, the position you appear to be taking seems highly implausible on your own "blockworld" viewpoint. Why would a "blockworld" just suddenly have an "edge" for no reason? It seems much more reasonable to expect any "blockworld" to extend as far as the math says it can.

As I explained in the Insight, EEs of GR constitute the constraint. Any solution of EEs that maps onto what you observe or could conceivably observe is fair game. There is nothing in GR that says you must include extensions of M beyond what maps to empirically verifiable results. But, if you have a prediction based on ##a = 0## and ##\rho = \infty##, by all means include that region.

Not at ##t = – B##. There the density ##\rho## is infinite.

Yes, there is, because in the 4D global self-consistent view, the manifold is its maximal analytic extension. Arbitrarily cutting it off at some point prior to that makes no sense on that view. If you think it does because of some "adynamical constraint", what is that constraint? It can't be "because RUTA prefers to cut off the solution at ##t = 0## in his model".

Not if you want your model to make testable predictions about observations that haven't been made yet.

Right, the singularity theorem is not violated because it is still true that there are timelike and null geodesics with finite affine parameter lengths into the past (finite proper time). But, all the observables and physical parameters are finite (except meaningless ones like the volume of spatial hypersurfaces of homogeneity). It is absolutely "artificial" in that there is no dynamical reason whatsoever for not extending the solution into the past (with negative values of t) all the way to ##a = 0##. But, in the 4D global self-consistent view, there is no reason to do that. You only need as much of the spacetime manifold as necessary to account for your observations. I don't foresee a need for ##\rho = \infty##, i.e., ##a = 0##, but if we ever do need such ##\infty##, then you can include it at that point.

Ok, then yes, I agree you can pick ##a(0) \neq 0## in your solution, and, as far as I can tell, that also makes ##\dot{a}##, ##\ddot{a}##, and ##\rho## finite at ##t = 0## (basically because you have substituted ##t + B## for ##t##, so all of the values at ##t = 0## are proportional to some power of ##B## instead of diverging).

However, this model is obviously extensible to negative values of ##t##, and when you reach ##t = – B##, your model has ##a = 0## and ##\dot{a}##, ##\ddot{a}##, and ##\rho## all infinite. So your model is not a different model from the standard one, it's just a shift of the ##t## coordinate by ##B## (strictly speaking there is a rescaling of ##t## as well). Considering the patch ##t \ge 0## in this model is simply equivalent to only considering the patch ##t \ge B## in the standard Einstein-de Sitter model. This is not a model in which the singularity theorems are violated; it's just a model in which you have artificially restricted attention to a particular patch.

Yes

Thank you for the pointer, it's much better to talk about a specific model.

Do you mean equation (18) in the Insight?

Go to this Insight and you'll see the solution I'm talking about. I have not said anything "mathematically incorrect." I assumed you were familiar with the differential equation resulting from the spatially flat, matter-dominated cosmology model called Einstein-deSitter, which is the differential equation I am solving. The only dispute you have raised here is that you claim the EdS solution entails ##a(0) = 0##, while I am using the term to mean the spatially flat, matter-dominated model. We can argue semantics if you like, but it doesn't change anything.

I'm using the same terms you used. I'm just correcting your erroneous usage of them.

Then you need to show me one, because the EdS model is not one.

I have said nothing at all about my personal preferences. If you make statements that are wrong as a pure matter of math, you should expect to have them corrected. Correcting them is not "bias", it's just correcting erroneous statements. Your claim that the EdS model is "without infinities" is wrong as a pure matter of math: the EdS is a specific solution of a specific equation with specific properties, and those properties include ##a = 0## at ##t = 0##.

Your claim that there might be some solution of the EFE that is spatially flat, matter-dominated, but without any point at which ##a = 0## might be true; but you can't just wave your hands and claim it. You need to show such a solution, or prove that one exists. You have done neither. My pointing that out is not "bias"; it's just asking you to show your work.

You're arguing semantics now. Call it something else, then. The point is, we have a solution of EE's for the spatially flat, matter-dominated cosmology model without infinities. If this solution bothers you, you need to ask yourself, "Why does this solution bother me?" Wald was clear about why it would bother him, but that is purely dynamical bias.

The Einstein Field Equation is a second-order differential equation, for which you can freely choose as you say.

The Einstein-de Sitter model is not; it is a particular solution to that equation, in which there is no more freedom to choose ##a(t)##; it's exactly specified for the entire solution.

A mathematical fact about the wrong thing. See above.

It's a second-order differential equation, of course you can freely choose ##a(t)## at two different times to find a particular solution. There is no quibble, it's a mathematical fact.

You can't; the Einstein-de Sitter model is a known exact solution of the EFE and has ##a(0) = 0##.

I suppose you could quibble about this by changing coordinates so that the value of ##t## where ##a = 0## is not ##t = 0##; but it will have ##a = 0## at some value of ##t##. That is a known geometric property of the model.

You seem to be confusing the (true) statement that the singularity theorems by themselves don't tell you very much about the actual properties of the singularities, with the (false) statement that you can just handwave any kind of singularity you want into a specific model. We know a lot more about the EdS model than just what the singularity theorems tell us.

If you want to construct some other model that looks like the EdS model for some range of ##t## (such as, for example, redshifts smaller than ##z = 1000## or so), but then differs at values of ##t## before that, that's fine. If you can show that such a model, while satisfying the premises of the singularity theorems and therefore being geodesically incomplete, nevertheless has ##a(0) \neq 0##, that's fine too. But you can't just wave your hands and say "EdS model" to do that; you have to actually construct the other model and show that it has the properties you claim it has.

If you choose to have the "beginning" be at ##a(0) \neq 0## in the EdS model, for example, then you have a "singularity" per their definition. It's "pathological" because "it is possible for at least one freely falling particle or photon to … have begun its existence a finite time ago." That's only pathological from the dynamical perspective, as I explained using the thrown ball example.

Or a pointer to a paper or other reference that describes the sort of model you are referring to would be fine.

Yes, I know that, strictly speaking, "singularity" means "geodesic incompleteness".

Why? Since you appear to be saying the spacetime in the model you describe here is extendible past ##t = 0## indefinitely (i.e., to arbitrary negative values of ##t##), then geodesics in the model would be similarly extendible. So the spacetime in your model would not be geodesically incomplete, hence would not contain a singularity.

If you think your model would still be geodesically incomplete while still being extendible indefinitely past ##t = 0##, then you will have to give quite a bit more detail about your model, because I don't understand how it would be, given what you have said so far and what kind of model you appear to be interested in.

If we then went out and checked that the physical content of events matched that predicted by the constraint, that would be clearly scientific and sensible. I don't think it is required that the data on each leaf of a foliation of ##\mathcal{M}## must be related to that on any other leaf via some Green's function or other expression of dynamical propogation in order for the theory to be scientific or count as an explanation.

Classical theories were always such that data on later leaves followed from that on earlier leaves via integration against some kernel (or similar), but I don't think this must be true.

You have to look at what they proved. If you have a copy of Wald, read chapter 9 section 1, "What is a Singularity?" I'm not going to type that entire section here, but you'll find that the notion of a singularity is difficult to define, so the singularity theorems proved "the existence of an incomplete timelike or null geodesic." That such a place is exists is deemed "pathological" because "it is possible for at least one freely falling particle or photon to end its existence within a finite "time" (i.e., affine parameter) or to have begun its existence a finite time ago." So, my choice of ##a(0) \neq 0## would satisfy their definition of a singularity. It's not infinite density or infinite curvature, it's an entirely well-behaved "singularity," so I am not calling it a singularity. Here is the last sentence in that section, "Unfortunately, the singularity theorems give virtually no information about the nature of the singularities of which they prove existence."

Since the Einstein-de Sitter model satisfies the conditions of the singularity theorems (assuming you mean the model described on this Wikipedia page), it must have an initial singularity. Whether you call the point of that initial singularity ##a(0) = 0## or redefine your coordinates so the singularity occurs at some coordinate time before ##t = 0## doesn't make a difference to the global geometry of the solution.

I have made no such claim, so I don't see why I should have to justify it.

You don't appear to even be reading what I'm actually saying. I'm just asking which of these two options you are choosing:

(1) You are disputing that the singularity theorems are mathematically correct: you think there can be a model that satisfies all of the premises of the singularity theorems but does not have an initial singularity; or

(2) You are accepting that the models you are interested in, which do not have initial singularities (and I am not in any way disputing that you can have legitimate reasons for being interested in such models), violate at least one of the premises of the singularity theorems (the obvious ones to violate would be the energy conditions, since we already know inflationary models and models with a positive cosmological constant violate them anyway).

I don't see a third option.

So, you tell me, why do I have to past extend beyond ##a(0) \neq 0## to a singularity in a simple Einstein-deSitter model for example?

I'm sorry, but whatever they were "looking for" is irrelevant to what the theorems actually say mathematically. Any claim that you can "choose" to just make the model not have a singularity can only be true if your model violates at least one of the premises of the singularity theorems. That is true regardless of what the intentions of the people who proved the theorems were.

I have said nothing whatever about what I personally would or would not be "satisfied" with. I am simply pointing out a mathematical fact that it seems to me that any claim about solutions must take into account. Are you disputing this mathematical fact? If not, then you must acknowledge that any solution that has the property you appear to prefer (not having an initial singularity) must violate at least one of the premises of the singularity theorems.

If you have a spacetime that meets the conditions of the singularity theorems, and which therefore has an initial singularity, it seems to me that the singularity theorems themselves would provide an adequate nondynamical explanation of the initial singularity, since, as I've said, those theorems are not dynamical, they're geometrical.

Correct, you're trying to find a 4D model to account for all the data and our models go well beyond 5000 years into the past to do that. But, not all the way to a singularity.

They're looking for past extendability and found it. Why were they looking for that? Because they were thinking dynamically. Here is an analogy.

Set up the differential equations in y(t) and x(t) at the surface of Earth (a = -g, etc.). Then ask for the trajectory of a thrown baseball. You're happy not to past extend the solution beyond the throw or future extend into the ground because you have a causal reason not to do so. But, the solution is nonetheless a solution without those extensions. Same for EEs with no past extension beyond a(0) and a choice of a(0) not equal to zero. Why are you not satisfied with that being the solution describing our universe? There's nothing in the data that would ever force us to choose a(0) = 0 singular. The problem is that the initial condition isn't explained as expected in a dynamical explanation. All we need in 4D is self-consistency, i.e., we only have to set a(0) small enough to account for the data. Maybe someday we'll have gravitational waves from beyond the CMB and we'll be able to push a(0) back to an initial lattice spacing approaching the Planck length. But, we'll never have to go to a singularity.

If "make no sense" just means you prefer a physical theory that says they're not physically valid, that's fine. But they make perfect sense from the standpoint of logical and mathematical consistency.

Only if you wish to ignore the wealth of astronomical data we have.

It doesn't matter what the "point" of them was; they are mathematical theorems. If the premises are satisfied, the conclusions hold.

The theorems themselves are not dynamical, however the people who proved them might have been "thinking". The theorems are geometric: they say that any spacetime that satisfies the premises of the theorems and has a certain geometric property (a trapped surface) also must have another geometric property (a singularity).

Only if the model violates at least one of the premises of the singularity theorems.

The point of the singularity theorems was only to find out whether the initial singularity could be avoided if you went to inhomogeneous/anisotropic models. The answer was "no," but that's because they were still thinking dynamically. My point is simply that you can avoid the singularity in a homogeneous/isotropic model by simply choosing a(0) not equal to zero. EE's give an ordinary, second-order differential equation in a(t), so you are free to choose a(0) and a(some other t, typically chosen to be today) to find a particular solution. The past extendability (backwards from a(0)) is only an issue for dynamical thinking. Thinking adynamically, the globally self-consistent, 4D solution with nothing preceding a(0) is fine.

"Cannot" misstates what this model says. The traveler does not do anything to prevent repetition, because there is only one "copy" of the closed timelike curve and at each event on it, only one thing is possible. Even if the traveler has some sort of "free choice" at an event on the curve, there is still only one copy of that event, so he can only make one choice at it. It's no different from your only being able to make one choice about what to do at, say, noon this Tuesday. Even if you are on a CTC and pass the event "noon this Tuesday" an infinite number of times, it's still just one event and you can only make one choice about what to do at it.

It's true that all this does not seem anything like our intuitive concept of "making a choice". But that's because our intuitions about such things are not based on any experience with closed timelike curves, since no human has ever had one as their worldline.

This seems to contradict the Hawking-Penrose singularity theorems, unless you are only talking about spacetimes that violate the premises of those theorems (such as inflationary models). The singularity theorems require ##a(0) = 0## for spacetimes that satisfy their premises; that's what "singularity" means.

You're trying to think dynamically about the block universe. That is exactly how one gets into trouble, as I explain in my Insight.

That is purely a dynamical bias. You're fine to keep it, but it does not in any way refute the point I'm making.

That you equate mysticism with least action principles explains your hostility.

That association is pure rhetoric, astrology has no proven explanatory power while constraints such as conservation of momentum, angular momentum, and energy have proven to be extremely powerful. You clearly have a bias against block universe explanation that has nothing to do with its explanatory power in physics.

You are responsible for acquiring the knowledge needed to render informed critiques. If you cannot acquire the book, e.g., via interlibrary loan, then contact the author directly. An interested physicist in India just contacted me last week for example. He said the price of the book is too high and no cheaper alternatives exist at this point, so I sent him links and papers covering all the aspects he's interested in. I did not write this book to make money, our currency as scholars is ideas.

Close, but the point is that mass is a relational property of matter, not an intrinsic property.

The point is that our 4D, self-consistency view of physics leads to entirely different approaches to DM and DE. The reason for having that in the book is merely to show the potential of adynamical thinking on the heels of showing its explanatory power. I have no real stake in whether these ideas are ultimately accepted as resolutions to DM and DE. That misses the point entirely. Again, that adynamical thinking is responsible for generating these approaches is a fact. Whether or not you like adynamical explanation is irrelevant.

There is only "once around" in the block universe.

Exactly, the entire book and many of my Insights were written to make this point: If you accept constraint-based explanation as fundamental to dynamical explanation, many mysteries of modern physics disappear. Then we see that the physics is correct, it's the practitioners that are mistaken. Whether or not you like this point is another matter altogether and in no way refutes the point.

There are two mysteries about the Big Bang, both resulting from dynamical explanation via time-evolved causal mechanisms from initial conditios and both resolved by adynamical explanation via constraints per 4D self consistency. The initial conditions in dynamical explanation are independent of the causal mechanisms and for cosmology, they are therefore a mystery. That is resolved in the self-consistency approach because initial conditions are just as explanatory as any other point on the spacetime manifold. As for the initial singularity, that is also avoidable in at least two ways via adynamical means. For example, one may simply choose the scaling factor to be something other than zero at t = 0. The second-order differential equation for the time evolution of a(t) does not demand a(0) = 0. That is a result of dynamical thinking. The second is the “stop-point problem” of Regge calculus, where you can pick your fundamental lattice spacing based on whatever you like.

Why this worry about being banned? You would not get immediately banned for discussing a work that is borderline in meeting our standards. The mentors will discuss it and advise if its ok to continue to discuss. And no I do not agree that the preferred frame in GLET is the same as the aether in LET, but that is for a discussion on it, not this thread.

Thanks

Bill

If you're truly traveling around a loop (a closed timelike curve), then each time you reach a particular event, your memory state must be the same as all the previous times you reached that event. Otherwise the physical state at that particular event would not be fixed, and it must be.

Just an observation with my mentors hat on – is such a comment really productive? You probably do not know this but Ruta and I have different interests in physics – mine is more mathematical. For example he is quite interested in the the Blockworld view of physics – but its not something I am into. Ruta knows this and actually counselled me that getting his book may not suit me. I did buy it because Ruta is a knowledgeable member of our community here and I was interested in his view. Again as a mentor if anyone started actually forcibly touting books they wrote, or chided anyone for not buying such etc, they would be warned.

Thanks

Bill

I think I have explained before that what is banned is, except in the area of a historical discussion, LET – ie a theory that involves not only a preferred frame, but a medium that light is supposed to undulate in, have physical effects that shorten objects when they move in it etc. The reason is it is unobservable and superseded by a theory based on simpler testable symmetry assumptions. You can discuss a preferred frame as part of discussions of peer reviewed papers, textbooks, lectures by reputable scientists etc. But discussing it as part of personal theories you may have is not allowed. GLET you mentioned before is borderline because I do not think it ever got past the peer review process. However from my relativity newsgroup days many knowledgeable people did think it was of publishable quality, as do I. If that is what you wanted to discuss, then the mentors would need to approve it.

Thanks

Bill

GR and the Big Bang

GR and Closed Timelike Curves

Do not pretend to understand my motives for doing this work. And you should read the work before making any comments pertaining thereto. Here are three published papers for the DM and DE results where we fit galactic rotation curves (THINGS data), the mass profiles of X-ray clusters (ROSAT and ASCA data), the angular power spectrum of the cosmic microwave background (CMB, Planck 2015 data), and the supernova type Ia curve (SCP data) all without DM or DE meeting or exceeding other fits, e.g., metric skew-tensor gravity (MSTG), core-modified NFW DM, scalar-tensor-vector gravity (STVG), ΛCDM, MOND, and Burkett DM. Are those the kinds of analyses you do in astrology? I don't study astrology, so I wouldn't know.

Again, you should not criticize an idea out of ignorance. Read the relevant material and then render informed feedback. Here is a paper relating the physics and consciousness to appear in an edited volume.

Got it from here:

https://en.wikiquote.org/wiki/David_Mermin'Richard P. Feynman in a letter to N. David Mermin, related to his AJP paper Bringing home the atomic world: Quantum mysteries for anybody, American Journal of Physics, Volume 49, Issue 10, pp. 940-943 (1981), as quoted in Michelle Feynman (2005). Perfectly Reasonable Deviations from the Beaten Track. Basic Books. p. 367. ISBN 0-7382-0636-9.'

Would you please send me a reference for that? I'll add it to this Insight and a paper we're writing. Thnx

https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/76f3/9c8a412b47b839ba764d379f88adde5bccfd.pdf

Feynman in a letter to Mermin said 'One of the most beautiful papers in physics that I know of is yours in the American Journal of Physics.'

I personally am finding my view of QM evolving a bit. Feynman said the essential mystery of QM was in the double slit experiment. I never actually thought so myself, but was impressed with it as an introduction to the mysteries of QM at the beginning level. I am now starting to think entanglement may be the essential mystery.

Thanks

Bill

Dynamical explanation also gets you into trouble in GR and constraint-based explanation comes to the rescue there, too (I have Insights on that). It then leads to entirely new approaches to dark matter, dark energy, unification, and quantum gravity (see Chapter 6 of our book). If it was only in QM that adynamical explanation bailed you out, maybe people would consider giving up NPRF in SR and using a preferred frame in QM. I choose constraint-based explanation motivated by NPRF as fundamental to time-evolved, causal explanation for the reasons articulated here and in Chapters 7 and 8 of our book (having to do with the hard problem of consciousness). It gives me coherence and integrity in my worldview as a whole. It’s just a personal preference, though.