Have Scientists Seen an Electron? How We Detect Them

Table of Contents

Have Scientists Seen an Electron? Why Seeing Isn’t Enough

This article is not about literally seeing a single electron with your eye; it addresses the broader—and common—belief that direct visual perception is the only valid form of evidence. I will show that the human eye, as a light detector, is NOT a reliable detector in many respects, and therefore using it as the sole standard to validate phenomena is irrational.

Context: why this question keeps appearing

I often see statements on forums that question or dismiss things simply because they cannot be “seen.” A recurring example is the claim that we “haven’t seen an electron.” A few representative threads:

- Concept of probability wave

- Bifurcation of the mind

- Translating English into mathematical equations

- Chicken or the egg

- No scientist has ever seen an electron

- Indisputable proof that electrons exist

I could list many more examples, but the point is clear: people often treat “seeing” as the end-all test of reality. My goal here is to explain why “seeing” is overrated as a scientific criterion.

What do we mean by “seeing”?

Most people mean “seeing with the human eye.” If examined, that implies a sequence of events: (i) visible light from some source reaches an object; (ii) light from the object travels to our eyes; (iii) our eyes convert that light into electrical signals; (iv) those signals are processed by the brain and we perceive the object. That chain is what people mean when they say they “saw” something with their own eyes.

Limitations of the human eye as a detector

By that description it is clear the eye is limited. Human eyes detect only electromagnetic radiation in a very narrow band—the visible spectrum. If something either does not emit electromagnetic (EM) radiation, or emits EM radiation outside the visible range, we cannot see it directly.

Example: electrons and cloud chambers

An electron is a charged particle. The eye cannot directly “see” a single electron, even if it hit your eyeball. But we can still detect electrons visually via indirect effects. For example, in a cloud chamber a high-energy electron ionizes gas molecules as it moves; those ions become nucleation sites for condensation, leaving a visible trail. In that sense we have “seen” the track made by an electron rather than the electron itself.

Other senses and external detectors

Our eyes are not the only detectors available to us. We cannot see wind, yet we can hear and feel moving air. We cannot see infrared (heat), but we can feel it on our skin or image it with instruments. The eyes are just one of many biological detectors; scientific detectors extend far beyond what our senses can do.

Two clear shortcomings: wavelength range and sensitivity

- Narrow spectral range. The eye responds only to visible wavelengths.

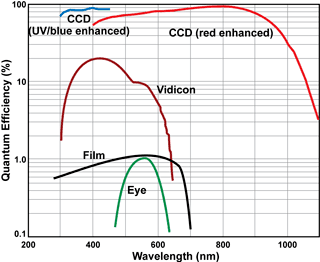

- Low quantum efficiency (QE). The peak QE of the eye is about 1% near 550 nm, meaning roughly 1 out of 100 incident photons is detected on average. Compare that to electronic detectors such as vidicons or CCDs, which cover a much wider spectral range and have much higher QE.

Because of these limits, using unaided vision as the sole criterion for reality is not rational.

Temporal resolution: the eye is slow

The eye and visual system also have limited time resolution. Movies are a useful illustration: traditional film at 24 frames per second presents one frame every ≈0.04 s, and the visual system tends to hold an image for roughly 0.02 s. Consequently, events that occur faster than about 0.02–0.04 s are not perceived as distinct.

By contrast, many photodetectors used in physics have time responses in the nanosecond or even picosecond range. For example, GaAs photocathodes used in accelerators have measured full-width-at-half-maximum responses on the order of picoseconds. That is orders of magnitude faster than the human eye.

Conclusion: “seeing” is not the final word

The simple test “Do I see it?” fails as a universal standard because it relies on an instrument (the eye) that is spectrally narrow, relatively insensitive, and slow. A little analysis—define what “seeing” means, then analyze the detector being used as the criterion—quickly shows that many dismissals based solely on “we can’t see it” are unfounded.

Have scientists seen an electron?

Short answer: no—scientists have never “seen” an electron in the same way we see everyday objects by direct visible-light imaging. Electrons are far smaller than the wavelength of visible light, so direct imaging with visible photons is impossible. Instead, physicists rely on indirect evidence and recording techniques (tracks, detector signals, scattering experiments, tunneling microscopy images of charge distributions, etc.) to infer electron properties. Those methods produce extremely robust, reproducible information—electrons are among the best-understood particles in physics—even though they are invisible to unaided human sight.

Related: See what an atom looks like

PhD Physics

Accelerator physics, photocathodes, field-enhancement. tunneling spectroscopy, superconductivity

“Because there are people who simply have no trust in authority, and who are not willing to accept authority.”

Then those are the people who live out in the woods, devoid of any contact with civilization. After all, for them to use their cellphones, fly in an airplane, or go to a doctor will all require that they be an expert in Special Relativity, General Relativity, Quantum Mechanics, Medicine, etc… These backwoods, isolated folks are not the one I encountered who asked me if I have “seen” an electron, and they are also not the ones who posted in all those threads that I cited in the article, because that will imply that they have to use some modern electronics and will have to know solid state physics and material science.

We have ended up with making too many claims and too many characterization of “other” people as strawmen to argue against this. If you are not one of them, don’t speculate on their behalf unless you are willing to defend such a thing. The article points to the fallacy of just your eyes as the final arbiter of what is real and what exists based on the fact that our eyes are very poor and limited detectors.

Now, this is BEFORE I argue on the fact that our eyes and our “observation” can easily be fooled. We are not only limited by many optical illusions, but what we see has to be processed by our brains, which in itself has its own set of issues. I can point out to you studies in which people swear they saw something that never happened (seeing Bugs Bunny at a Disney theme park) simply via a suggestion. Now, did their eyes actually saw that? But they claim they did, so it is as “real” to them as anything else.

So now, not only do we have a physical shortcoming in terms of our optical system alone, but we also have a shortcoming in terms of how human being actually decide if he/she actually saw something in how the brain process on what we believe we saw.

And this is the device that these people will trust in.

Zz.

Yes. You have to trust. People often have a problem with that because giving that trust may mean hard work in actually learning some theory rather than some easier, half baked ideas. Imo, that’s often the reason for choosing a model. (It is such a shame to be maths phobic, in particular.)

“That sort of implies equal weighting to the expert view and my uninformed view. How can one hang on to an uninformed view on the off chance that it could possibly be right (the probability being based on ignorance, perhaps).”

Because there are people who simply have no trust in authority, and who are not willing to accept authority. I am not one of them, so please do not blame the existence of such people on me.

I also mentioned the alternative which is simply to believe what is claimed by those who are considered experts. But then again, how do you know who has the best expertise? If you are lacking the knowledge to judge on subject yourself, then it seems likely that you are also lacking the knowledge to decide who is competent with respect to that subject. So again, you have to trust the judgement of others.

At the end, it is all about trust: If you cannot judge yourself, you have to trust the judgements of others.

“I always thought that not taking a position is the main point about agnosticism. But if you think that agnosticism refers to a specific motive for not taking a position, then let’s just call it “not taking a position”.”

That sort of implies equal weighting to the expert view and my uninformed view. How can one hang on to an uninformed view on the off chance that it could possibly be right (the probability being based on ignorance, perhaps). This has been the approach of medical quackery and many people have suffered accordingly.

Science is agnostic by nature. Science admits to the ever present possibility that, tomorrow, a theory may arrive and turn everything upside down. But you owe it to yourself to to commit to what you have found to be right until there’s some damned good evidence to the contrary.

“That’s not quite right…. In that case your choices are to believe what the experts tell you, or to decline to take any position on the grounds that you haven’t studied the issue yourself. The latter is not an agnostic position – the agnostic position is that the truth is unknowable, so actively denies the possibility that the experts have the answer when the agnostic does not.”

I always thought that not taking a position is the main point about agnosticism. But if you think that agnosticism refers to a specific motive for not taking a position, then let’s just call it “not taking a position”.

The word is EVIDENCE. You couldn’t trust your eyes alone, even if you somehow thought you had ‘seen’ an electron. Have you ever ‘seen’ a distant galaxy (except as a photograph)? Have you ever ‘seen’ a tektonic plate moving? Why does the phrase “believe the experts” read as being dismissive? If we didn’t have experts, we would have no medicine, engineering or chemistry; we need to believe them and, when several of them agree and present evidence, that is more than enough to be going on with. On the other hand, when we see Penn and Teller, we don’t actually believe that the little guy’s head has just been cut off.

“It just means: I am unable to verify this myself. So either I just believe what the so-called experts tell me, or I have to take an agnostic position.”

That’s not quite right…. In that case your choices are to believe what the experts tell you, or to decline to take any position on the grounds that you haven’t studied the issue yourself. The latter is not an agnostic position – the agnostic position is that the truth is unknowable, so actively denies the possibility that the experts have the answer when the agnostic does not.

The “No one has seen an electron with their own eyes” argument sets teeth on edge because it ignores this distinction, promoting the arguers lack of knowledge into a universal truth.

“But even you have to admit that this is not what the article was about.”

Sorry, it was not my intention to bash your article. The article is well-written, and I enjoyed reading it.

If I was allowed to propose one improvement, it would probably be to put more emphasis on the commonalities between “detecting something with your eyes, ears or sense of touch” and “detecting something with external tools”.

“It is about the use of one’s eyes as the sole determination of what “exists” and what doesn’t!”

I get your point, and you certainly did a great job explaining why external tools can be much better detectors than our natural senses. But for some of the sceptics the challenge might rather be to understand what the process of detecting something with an external tool has in common with the process of detecting something with our natural senses.

“If you insist that it is justifiable that people who do not understand the physics involved with electrons, and that the ONLY way that they can be convinced that electrons exist is by seeing them with their own eyes (i.e. using a very poor detector), then we have nothing more to talk about here.”

You are completely right: Our eyes are indeed very poor detectors when compared with a CCD. But we all had much time to get used to our eyes, and we all (at least those of us who can see) have acquired a great part of our knowledge about “the world” by observing it with our eyes. Trust is closely related with familiarness. People are confident that they can judge about a chain of evidence that they can see with their eyes, simply because they are so familiar with this process.

“It means that they are lacking the required background knowledge (or in some cases even the cognitive capability) to verify the presented chain of evidence, and they are not willing to just believe what they are told by someone who claims that he can.

The problem is that if you are unable to verify a presented chain of evidence yourself, then you have to believe in the judgement of others who claim that they can. With respect to natural sciences that might not be an issue for you, but there might be other areas where even you are lost.

Let’s assume for example, that some law expert presents you a chain of legal arguments that you are completely unable to verify on your own. Then you might say something like “On the high seas and before the court, one’s fate is in Gods hand”. And this is actually the same category of statement as “Nobody has ever seen an electron”. It just means: I am unable to verify this myself. So either I just believe what the so-called experts tell me, or I have to take an agnostic position.”

But even you have to admit that this is not what the article was about. It is about the use of one’s eyes as the sole determination of what “exists” and what doesn’t! If you insist that it is justifiable that people who do not understand the physics involved with electrons, and that the ONLY way that they can be convinced that electrons exist is by seeing them with their own eyes (i.e. using a very poor detector), then we have nothing more to talk about here.

Zz.

“”.. an allegory for the fact that the subject is too abstract for them… ” What does that even mean?!”

It means that they are lacking the required background knowledge (or in some cases even the cognitive capability) to verify the presented chain of evidence, and they are not willing to just believe what they are told by someone who claims that he can.

“Just because “they” didn’t understand it doesn’t make it abstract and unobservable.”

The problem is that if you are unable to verify a presented chain of evidence yourself, then you have to believe in the judgement of others who claim that they can. With respect to natural sciences that might not be an issue for you, but there might be other areas where even you are lost.

Let’s assume for example, that some law expert presents you a chain of legal arguments that you are completely unable to verify on your own. Then you might say something like “On the high seas and before the court, one’s fate is in Gods hand”. And this is actually the same category of statement as “Nobody has ever seen an electron”. It just means: I am unable to verify this myself. So either I just believe what the so-called experts tell me, or I have to take an agnostic position.

“A “concrete form of evidence”, for most people, implies seeing it with their own eyes.”

But, of course, they don’t [U]always[/U] want to ‘see’ something with their own eyes. The typical person we are discussing is quite prepared to believe all sorts of ‘evidence’, even when presented third hand, on the grounds that they ‘could understand that’ and the information reinforces their prejudices. The daft arguments for and against medical treatments are an example.

I guess we’re just saying that people are fallible and we happen to be taking offense about their attitude, particulalry when it happens to go against [U]our[/U] special ‘loves’. So we are actually being no more rational than the others. (You just can’t win).

“Actually I see where he’s coming from. He is pointing out that some people demand a concrete form of evidence of things before they are prepared to acknowledge its existence or even that ‘scientists’ could understand those things. That attitude makes me smile when people post ideas like that, using electrons all the time for their communication.

PS I was looking for a better word than “allegory” but couldn’t come up with one. I assume you agree with the meat of his comment – but I found your post equally abstruse, I’m afraid. :smile:”

But that is the whole point of the article. A “concrete form of evidence”, for most people, implies seeing it with their own eyes. My argument here is that your eyes that you’ve been using as the standard bearer for detection are very poor, and worse than many detectors that we have!

However, if people are demanding they should be able to see an electron with their eyes because electrons are something “too abstract” for them, then the issue here isn’t the detection, but the understanding of what electrons are! After all, physicists won’t argue that electrons do not exist simply because they can’t see them with their eyes. So just because something appears abstract to you, it doesn’t mean that you need to see it for you to accept that it exists. After all, brain surgery is “abstract” to me. Do I dismiss it simply because I don’t understand it? Do I really need to see brain surgery in action with my own eyes for me to accept that it can be done?

Zz.

“”.. an allegory for the fact that the subject is too abstract for them… ” What does that even mean?!

Is it like claiming ignorance of a law after you’ve broken it? “Sorry officer, I didn’t know I was breaking the law!” How well does that go?

Just because “they” didn’t understand it doesn’t make it abstract and unobservable.

Zz.”

Actually I see where he’s coming from. He is pointing out that some people demand a concrete form of evidence of things before they are prepared to acknowledge its existence or even that ‘scientists’ could understand those things. That attitude makes me smile when people post ideas like that, using electrons all the time for their communication.

PS I was looking for a better word than “allegory” but couldn’t come up with one. I assume you agree with the meat of his comment – but I found your post equally abstruse, I’m afraid. :smile:

“All right. But when they complain that nobody has ever seen an electron, they are not claiming that their eyes are superior detectors. It’s more like an allegory for the fact that the subject is too abstract for them.”

“.. an allegory for the fact that the subject is too abstract for them… ” What does that even mean?!

Is it like claiming ignorance of a law after you’ve broken it? “Sorry officer, I didn’t know I was breaking the law!” How well does that go?

Just because “they” didn’t understand it doesn’t make it abstract and unobservable.

Zz.

“There’s some important philosophy here that’s being ignored though.[/quote]

Important to whom?

[quote]I can’t recall the source of the quote or the quote itself, but there’s a quote of the form:

“We can build a model of how the hands of a watch tick and make predictions, but we can never open the watch to understand its inner workings”

or something like that. It’s very important, I think, to not make a terrible philosophical mistake engaged in by particle physicists in particular, and confuse our models with reality. So the question “Is an electron real? No one has ever ‘seen’ one” may be posed stupidly if the standard of existence is human eyesight, but it arises from something very important, which is curiosity about what the dividing line between what is an objective, external reality and what is not.[/quote]

But you are making an a priori assumption that there IS “an objective, external reality” that is somehow inaccessible to us. How would you even know such a thing exist? You are basing your argument on a unicorn. This is the worst part of “philosophy” and why such a topic isn’t allowed in this forum.

[quote]An electron, in many ways, is a complex, sometimes inconsistent network of mathematical and qualitative assertions,[/quote]

Say what? You stated this without any kind of justification or evidence. Show me where it is “sometimes inconsistent network of mathematical and qualitative assertions”.

[quote]since ordinary people don’t often ask such questions about, say, Zebras.”

They should, because their observation of zebras abide by the SAME set of rules. And in fact, I would assert that there are MORE definitive and quantitative observation of electrons than there are zebras. I can’t see zebras when it is dark, but I can still detect electrons with my detector!

But beyond all this, in your haste to sell your unobserved reality, you completely missed the whole point of the article. It has nothing to do with objective reality that you are so in love with. Rather, it has everything to do with how bad your eyes are as a detector. Is this something you do not agree with despite all of the evidence that I had presented?

Zz.

QuoteAnd apply such techniques to the pile of manure that one often hears in the media from politicians, etc., UnquoteI have the feeling that even if your prose was "required reading", there still would be a segment of the population that would remain unconvinced, and stubbornly comment "But still ….. "

All right. But when they complain that nobody has ever seen an electron, they are not claiming that their eyes are superior detectors. It's more like an allegory for the fact that the subject is too abstract for them.

There's some important philosophy here that's being ignored though. I can't recall the source of the quote or the quote itself, but there's a quote of the form:"We can build a model of how the hands of a watch tick and make predictions, but we can never open the watch to understand its inner workings"or something like that. It's very important, I think, to not make a terrible philosophical mistake engaged in by particle physicists in particular, and confuse our models with reality. So the question "Is an electron real? No one has ever 'seen' one" may be posed stupidly if the standard of existence is human eyesight, but it arises from something very important, which is curiosity about what the dividing line between what is an objective, external reality and what is not.An electron, in many ways, is a complex, sometimes inconsistent network of mathematical and qualitative assertions, and the fact that we cannot see it raises genuinely important questions about what the difference is between human models and objective reality, since ordinary people don't often ask such questions about, say, Zebras.