Types of Computer Languages: From Machine to High-Level

Table of Contents

Introduction

In this Insights Guide, the focus is entirely on types of languages, how they relate to what computers do, and how they are used by people. It is a general discussion and intended to be reasonably brief, so there is very little focus on specific languages. Please keep in mind that for just about any topic mentioned in this article, entire books have been written about that topic vs. the few sentences here.

Primary focus

The primary focus is on:

- Machine language

- Assembly language

- Higher-level languages

Also discussed

There is also discussion of:

- Interpreters (e.g. BASIC)

- Markup languages (e.g. HTML)

- Scripting languages (e.g. JavaScript, Perl)

- Object-oriented languages (e.g. Java)

- Integrated Development Environments (e.g. the .NET Framework)

Machine Language

Binary and early programming

Computers work in binary and their native language is strings of 1’s and 0’s. In my early days, I programmed computers using strings of 1’s and 0’s input to the machine by toggle switches on the front panel. You don’t get a lot done this way, but fortunately I only had to input a dozen or so instructions to create a tiny “loader” program. That loader would then read in more powerful programs from magnetic tape.

Why assembly emerged

It was possible to do more elaborate things directly via toggle switches, but remembering exactly which string of 1’s and 0’s represented which instruction was painful and error-prone. So, very early on the concept of assembly language arose.

Assembly Language

What assembly does

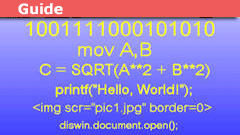

Assembly language represents each machine instruction’s string of 1’s and 0’s by a human-readable word or abbreviation, such as “add” or “ld”. These human-readable statements are translated to machine code by a program called an assembler.

Assembly trade-offs

Assemblers typically have an exact one-to-one correspondence between each assembly statement and the corresponding machine instruction. That differs from high-level languages, where a single high-level statement may generate dozens of machine instructions. Using assembly is effectively programming the machine directly: you use words instead of raw binary, but you still control registers, I/O, memory layout, and data flow explicitly—things not directly exposed in most higher-level languages.

CPU families and portability

Every CPU family has its own instruction set and therefore its own assembly language. That can be frustrating when moving to a new machine: a mnemonic like “load” may become “ld” or “mov” on another CPU, and instruction sets differ in what operations they support. That can force you to focus on machine-specific implementation details instead of concentrating on the algorithm you want to implement.

Assembly example

The advantage of assembly is precise control and maximum opportunity for optimization, which is useful for things like device drivers or extremely performance-critical code. The downside is that you must specify every detailed step the machine should perform. For example, an algebraic statement such as: A = B + COSINE(C) – D …must be decomposed into many explicit steps, for example (pseudo-assembly):

- Load memory location C into register 1

- Call subroutine “Cosine” (result back in register 1)

- Load memory location B into register 2

- Add registers 1 and 2 (result in register 1)

- Load memory location D into register 2

- Subtract register 2 from register 1 (result in register 1)

- Save register 1 to memory location A

And that’s a very simple algebraic statement—you must specify each step in the correct order, without mistakes.

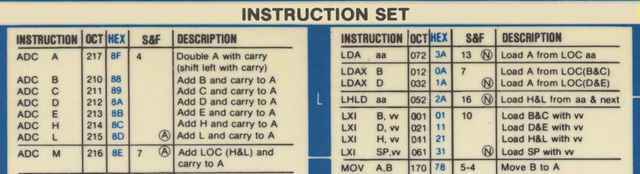

To illustrate, here’s a small portion of an 8080 instruction guide (octal and hex forms were often used during debugging):

Because of the tediousness of assembly programming, compilers were developed.

Compilers and Higher-level Languages

Benefits of compilers

Compilers remove the need to program the minutiae of registers and memory locations. They let you concentrate on the algorithm you want to implement rather than machine-level details. Compilers translate higher-level, more human-like statements into machine code. The downside is that when something goes wrong, mapping a high-level statement back to the machine-level behavior can be more difficult than with assembly or machine code; sophisticated debuggers are therefore essential.

As high-level languages add abstraction, the gap between what the programmer writes and what the machine executes increases. Modern programming environments reduce this pain: you often work inside an Integrated Development Environment (IDE) that includes compilers, debuggers, linkers, and other tools to help find and fix errors.

Early high-level languages

Early high-level languages included:

- Fortran (early 1950s)

- Autocode (1952)

- ALGOL (late 1950s)

- COBOL (1959)

- LISP (early 1960s)

- APL (1960s)

- BASIC (1964)

- PL/1 (1964)

- C (early 1970s)

Notable later languages

Subsequent notable languages include:

- Ada (late 1970s / early 1980s)

- C++ (1985)

- Python (late 1980s)

- Perl (1987)

- Java (early 1990s)

- JavaScript (mid-1990s)

- Ruby (mid-1990s)

- PHP (1994)

- C# (2002)

There were many others with varying degrees of impact. One lesser-known example is JOVIAL (Jules’ Own Version of the International Algorithmic Language), which I mention mainly because of the amusing name.

Special note about C: C became widely used and influenced many later languages. Operating system kernels (Unix, Windows, and earlier Apple systems) have significant portions written in C, with some assembly for device drivers. By design, C is closer to assembly than most high-level languages. Java is more widely used today in some areas, but C remains popular.

Interpreters, Scripting, and Command Languages

How interpreters work

Interpreters differ from assemblers and compilers: rather than generating object code to run later, an interpreter translates and executes statements on the fly, one statement (or even part of a statement) at a time. The low-level details such as register use are hidden from the programmer.

Interpreter pros and cons

The obvious trade-off is performance: interpreted code is typically slower than compiled code. However, modern hardware often makes speed less of an issue, while the advantages of interpreters—faster edit-test cycles and interactive debugging—remain important. You can frequently pause execution, modify variables or code, and resume interpretation.

Because interpreters often execute statements sequentially, some syntax errors only appear at the moment a specific path is interpreted. Assemblers and compilers process source code more fully before execution and can detect many syntax errors earlier. Some interpreters perform a pre-execution pass to catch errors ahead of time.

Examples of interpreted and scripting languages

BASIC was the first widely used interpreted language. JavaScript is commonly interpreted in the browser (though modern engines may include just-in-time compilation). Another important scripting form is the command script or shell script (for example, DOS batch files or Unix shell scripts). Perl was historically popular for system administration and remains in use today because of its cross-platform support and versatility.

Markup Languages

HTML and its role

The most widely used markup language is HTML (HyperText Markup Language). HTML defines rules for encoding documents in a format that a browser can read and present. Although people sometimes call HTML “code,” it is technically data that describes structure and presentation rather than executable machine code.

Markup vs. programming

Markup differs from compiled or interpreted programming languages in that markup does not produce object code nor directly execute. Instead, a program (a browser) reads markup and uses it to construct a document or UI. Cascading Style Sheets (CSS) complement HTML by describing presentation rules. HTML5 and CSS extend the capabilities of web pages, but detailing them is beyond this article.

Embedding procedural code

Procedural code (for example, JavaScript) can be embedded in HTML. The browser treats JavaScript as a program to execute to make pages dynamic and interactive. Server-side procedural code (for example, PHP) can modify what is served to the client. JavaScript is typically interpreted but modern engines also compile it to machine code at runtime for performance.

Integrated Development Environments (IDEs)

What an IDE provides

Modern programming often takes place inside an IDE—an environment that bundles an editor, compiler, debugger, linkers, project management tools, and other facilities such as version control and object/class browsers. Many IDEs also provide drag-and-drop UI construction, automatic generation of boilerplate code, and language-integrated tools that hide low-level details from the developer.

IDE evolution

The line between a full IDE and a simpler environment is fuzzy, but IDEs in their modern form evolved significantly in the 1980s and 1990s and have continued to grow more powerful since then.

Language categories

To summarize, the basic types of computer languages are:

- Assembler

- Compiler-based (higher-level)

- Interpreted

- Scripting

- Markup

- Database (not discussed in this article)

Within those categories there are other important paradigms—most notably object-oriented and event-driven programming—which influence how programs are designed and executed.

Object-oriented Languages

OOP concepts

Traditional compiled high-level languages rely on subroutines and procedures. Object-oriented programming (OOP) organizes data and code into objects that combine state and behavior, enabling different design and reuse patterns.

Languages with OOP

C++ added object-oriented features to C but doesn’t require their use; you can write procedural C++ code. Java, by contrast, enforces object orientation: everything is part of an object. C# was created by Microsoft as a strongly object-oriented language; historically it was closely tied to Microsoft platforms, though the ecosystem has evolved since its introduction.

Objects and OOP provide flexibility and extensibility, but exploring them in depth is beyond this article’s scope.

Event-driven Programming

What is event-driven programming?

Traditional procedural programs follow a linear or explicitly controlled flow. Event-driven programs, common in GUI and interactive environments, respond to external events such as mouse clicks, key presses, or messages from other parts of the system. Event-driven design is built into many modern IDEs and operating systems and is essential for highly interactive, windowed applications.

Like object orientation, event-driven design has strengths and trade-offs; covering those thoroughly would require a separate discussion.

Generations of Languages

Language generations

Literature sometimes groups languages into “generations.” The categorization is not universally useful, but a rough mapping is:

- First generation – machine language

- Second generation – assembly language

- Third generation – high-level compiled languages

- Fourth generation – database and scripting languages

- Fifth generation – integrated development environments / declarative problem-solving systems

Newer languages generally extend capabilities rather than outright replace older ones. C and Fortran remain in widespread use in areas that rely on decades of libraries and proven implementations.

Closing note

[NOTE: I had originally intended to write a second Insights article covering some obscure topics not covered here, but I’m not going to get around to it, so I should stop pretending otherwise.]

Studied EE and Comp Sci a LONG time ago, now interested in cosmology and QM to keep the old gray matter in motion.

Woodworking is my main hobby.

I've got it about 1/3rd done but it's a low priority for me at the momentNo no! high priority! high priority! :biggrin:

Where's part 2?I've got it about 1/3rd done but it's a low priority for me at the moment

Where’s part 2?

Where does something like Scratch fall in these? Just another high-level language? Interpreted, or compiled?From the wiki page — https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Scratch_(programming_language) — it appears to be an interpreted language, from the comments near the bottom of that page.

Where does something like Scratch fall in these? Just another high-level language? Interpreted, or compiled?

What about the "dot" directives in MASM (ML) 6.0 and later such as .if, .else, .endif, .repeat, … ?

https://msdn.microsoft.com/en-us/library/8t163bt0.aspx

Conditional assembly does not at all invalidate Scott's statement. I don't see how you think it does. What am I missing?It's not conditional assembly (if else endif directives without the period prefix are conditional assembly), it's sort of like a high level language. For example:

;... .if eax == 1234 ; ... code for eax == 1234 goes here .else ; ... code for eax != 1234 goes here .endifThe .if usually reverses the sense of the condition and conditionally branches past the code following the .if to the .else (or to a .endif).

…there are still mission-critical and/or safety-minded industries where "virtual" is a dirty word.Yeah, I can see how that could be reasonable. OOP stuff can be nasty to debug.

But that does NOT even remotely take advantage of things like inheritance. Yes, you can have good programming practices without OOP, but that does not change the fact that the power of OOP far exceeds non-OOP in many ways. If you have programmed seriously in OOP I don't see why you would even argue with this.I guess it's a matter of semantics. There was a time when OOP did not automatically include inheritance or polymorphism. By the way, the full OOP may "far exceed non-OOP", but there are still mission-critical and/or safety-minded industries where "virtual" is a dirty word.

Personally, I am satisfied when the objects are well-encapsulated and divided out in a sane way. Anytime I see code with someone else's "this" pointer used all over the place, I stop using the term "object-oriented".

What about the "dot" directives in MASM (ML) 6.0 and later such as .if, .else, .endif, .repeat, … ?

https://msdn.microsoft.com/en-us/library/8t163bt0.aspxConditional assembly does not at all invalidate Scott's statement. I don't see how you think it does. What am I missing?

What really defines a assembly language is that all of the resulting machine code is coded for explicitly.What about the "dot" directives in MASM (ML) 6.0 and later such as .if, .else, .endif, .repeat, … ?

https://msdn.microsoft.com/en-us/library/8t163bt0.aspx

Paul, how come you didn't include LOLCODE in your summary?

:oldbiggrin:Mark, you are very weird :smile:

Paul, how come you didn't include LOLCODE in your summary?

:oldbiggrin:

Or polymorphism, another attribute of object-oriented programming.Right. I didn't want to bother typing out encapsulation and polymorphism so I said "things like … " meaning "there are more". Now you've made me type them out anyway. :smile:

But that does NOT even remotely take advantage of things like inheritance.Or polymorphism, another attribute of object-oriented programming.

With a macro assembler, both the programmer and the computer manufacturer can define macros to be anything – calling sequences, structures, etc. Even the individual instructions were macros, so by changing the macros you could change the target machine.DOH !!! I used to know that. Totally forgot. Thanks.

I suppose it depends on how much you include in the term object-oriented. Literally arranging you code into objects, making some "methods" public and others internal, was something I practiced before C++ or the term object-oriented were coined.But that does NOT even remotely take advantage of things like inheritance. Yes, you can have good programming practices without OOP, but that does not change the fact that the power of OOP far exceeds non-OOP in many ways. If you have programmed seriously in OOP I don't see why you would even argue with this.

I stopped doing assembly somewhere in the mid-70's but my recollection of macro assemblers is that the 1-1 correspondence was not lost. Can you expand on your point?With a macro assembler, both the programmer and the computer manufacturer can define macros to be anything – calling sequences, structures, etc. Even the individual instructions were macros, so by changing the macros you could change the target machine.

I never used Forth so may have shortchanged it.It's important because it is an interpretive language that it pretty efficient. It contradicts your "slow as mud" statement.

I totally and completely disagree. OOP is a completely different programming paradigm.I suppose it depends on how much you include in the term object-oriented. Literally arranging you code into objects, making some "methods" public and others internal, was something I practiced before C++ or the term object-oriented were coined.

As I read through the article, I had these notes:

1) The description of assembler having a one-to-one association with the machine code was a characteristic of the very earliest assemblers. In the mid '70's, macro-assemblers came into vogue – and the 1-to-1 association was lost. What really defines a assembly language is that all of the resulting machine code is coded for explicitly.I stopped doing assembly somewhere in the mid-70's but my recollection of macro assemblers is that the 1-1 correspondence was not lost. Can you expand on your point?

2) It was stated that it is more difficult to debug compiler code than machine language or assembler code. I very much understand this. But it is true under very restrictive conditions that most readers would not understand. In general, a compiler will remove a huge set of details from the programmers consideration and will thus make debugging easier – if for no other reason than there are fewer opportunities for making mistakes. Also (and I realize that this isn't the scenario considered in the article), often when assembler is used today, it is often used in situations that are difficult to debug – such as hardware interfaces.No argument, but too much info for the article.

3) Today's compilers are often quite good at generating very efficient code – often better than what a human would do when writing assembly. However, some machines have specialized optimization opportunities that cannot be handled by the compiler. The conditions that dictate the use of assembly do not always bear on the "complexity". In fact, it is often the more complex algorithms that most benefit from explicit coding.No argument, but too much info for the article.

4) I believed the article misses a big one in the list of interpretive languages: Forth (c. 1970). It breaks the mold in that, although generally slower than compilers of that time, it was far from "slower than mud". It's also worth noting that Forth and often other interpretive languages such as Basic, encode their source for run-time efficiency. So, as originally implemented, you could render your Forth or Basic as an ASCII "file" (or paper tape equivalent), but you would normally save is in a native form.I never used Forth so may have shortchanged it. Intermediate code was explicitly left out of this article and will be mentioned in part 2

5) I think it is worth noting that Object-Oriented programming is primarily a method for organizing code.I totally and completely disagree. OOP is a completely different programming paradigm. It is very possible (and unfortunately quite common) to code "object dis-oriented" even when using OO constructs.I completely agree but that does nothing to invalidate my previous sentence.Similarly, it is very possible to keep code objected oriented when the language (such as C) does not explicitly support objects.Well, sort of, but not really. You don't get a true class object in non-OOP languages, nor do you have the major attributes of OOP (inheritance, etc).

As I read through the article, I had these notes:

1) The description of assembler having a one-to-one association with the machine code was a characteristic of the very earliest assemblers. In the mid '70's, macro-assemblers came into vogue – and the 1-to-1 association was lost. What really defines a assembly language is that all of the resulting machine code is coded for explicitly.

2) It was stated that it is more difficult to debug compiler code than machine language or assembler code. I very much understand this. But it is true under very restrictive conditions that most readers would not understand. In general, a compiler will remove a huge set of details from the programmers consideration and will thus make debugging easier – if for no other reason than there are fewer opportunities for making mistakes. Also (and I realize that this isn't the scenario considered in the article), often when assembler is used today, it is often used in situations that are difficult to debug – such as hardware interfaces.

3) Today's compilers are often quite good at generating very efficient code – often better than what a human would do when writing assembly. However, some machines have specialized optimization opportunities that cannot be handled by the compiler. The conditions that dictate the use of assembly do not always bear on the "complexity". In fact, it is often the more complex algorithms that most benefit from explicit coding.

4) I believed the article misses a big one in the list of interpretive languages: Forth (c. 1970). It breaks the mold in that, although generally slower than compilers of that time, it was far from "slower than mud". It's also worth noting that Forth and often other interpretive languages such as Basic, encode their source for run-time efficiency. So, as originally implemented, you could render your Forth or Basic as an ASCII "file" (or paper tape equivalent), but you would normally save is in a native form.

5) I think it is worth noting that Object-Oriented programming is primarily a method for organizing code. It is very possible (and unfortunately quite common) to code "object dis-oriented" even when using OO constructs. Similarly, it is very possible to keep code objected oriented when the language (such as C) does not explicitly support objects.

[QUOTE="FactChecker, post: 5691027, member: 500115"]In my defense, I think that the emergence of 5'th generation languages for simulation, math calculations, statistics, etc are the most significant programming trend in the last 15 years. There is even an entire physicsforum section primarily dedicated to it (Math Software and LaTeX). I don't feel that I was just quibbling about a small thing.”Fair enough. Perhaps that's something that I should have included, but there were a LOT of things that I thought about including. Maybe I'll add that to Part 2

[QUOTE="FactChecker, post: 5689999, member: 500115"]Sorry. I thought that was an significant category of languages that you might want to mention and that your use of the term "fifth generation" (which refers to that category) was not what I was used to. I didn't mean to offend you.”Oh, I wasn't offended and I"m sorry if it came across that way. My point was exactly what I said … I deliberately left out at least as much as I put in and I had to draw the line somewhere or else put in TONS of stuff that I did not feel was relevant to the thrust of the article and thus make it so long as to be unreadable. EVERYONE is going to come up with at least one area where they are confident I didn't not give appropriate coverage and if I satisfy everyone, again the article becomes unreadable.

In my defense, I think that the emergence of 5’th generation languages for simulation, math calculations, statistics, etc are the most significant programming trend in the last 15 years. There is even an entire physicsforum section primarily dedicated to it (Math Software and LaTeX). I don’t feel that I was just quibbling about a small thing.

[QUOTE="phinds, post: 5689826, member: 310841"]To quote myself:and”Sorry. I thought that was an significant category of languages that you might want to mention and that your use of the term "fifth generation" (which refers to that category) was not what I was used to. I didn't mean to offend you.

[QUOTE="phinds, post: 5689826, member: 310841"]To quote myself: “Although it's a good article, I don't get why you didn't include ____, _____, and _________. Especially _________ since it's my pet language.By the way what does this word "overview" mean that you keep using?

[QUOTE="FactChecker, post: 5689803, member: 500115"]An excellent article. Thanks.I would make one suggestion: I think of fifth generation languages as including the special-purpose languages like simulation languages (DYNAMO, SLAM, SIMSCRIPT, etc.), MATLAB, Mathcad, etc. I didn't see that mentioned anywhere and I think they are worth mentioning.”To quote myself:[quote]One reason I don’t care for this is that you can get into pointless arguments about exactly where something belongs in this list.[/quote]and[quote]This was NOT intended as a thoroughly exhaustive discourse. If you look at the wikipedia list of languages you'll see that I left out more than I put in but that was deliberate.[/quote]

I think Latex can go into one of those language categories, and if it does looks like markup language is a fitting candidate.Anyway, great and enlightening insight.

An excellent article. Thanks.I would make one suggestion: I think of fifth generation languages as including the special-purpose languages like simulation languages (DYNAMO, SLAM, SIMSCRIPT, etc.), MATLAB, Mathcad, etc. I didn't see that mentioned anywhere and I think they are worth mentioning.

[QUOTE="Jaeusm, post: 5689649, member: 551236"]The entire computer science sub-forum suffers from this.”Oh, it's hardly the only one.

[QUOTE="phinds, post: 5689333, member: 310841"]Yes, I've notice this in many comment threads on Insight articles. People feel the need to weigh in with their own expertise without much regard to whether or not what they have to add is really helpful to the original intent and length of the article supposedly being commented on.”The entire computer science sub-forum suffers from this.

[QUOTE="vela, post: 5689416, member: 221963"]You kind of alluded to this point when you mentioned interpreters make debugging easier, but I think the main advantage of interpreters is in problem solving. It's not always obvious how to solve a particular problem, and interpreters allow you to easily experiment with different ideas without all the annoying overhead of implementing the same ideas in a compiled language.”Good point.

You kind of alluded to this point when you mentioned interpreters make debugging easier, but I think the main advantage of interpreters is in problem solving. It's not always obvious how to solve a particular problem, and interpreters allow you to easily experiment with different ideas without all the annoying overhead of implementing the same ideas in a compiled language.

[QUOTE="Greg Bernhardt, post: 5689338, member: 1"]No no no it's a great thing to do! Very rewarding and helpful! :)”Yeah, that's EXACTLY what the overseers said to the slaves building the pyramids :smile:

[QUOTE="jim mcnamara, post: 5689101, member: 35824"]Your plight is exactly why I am loath to try an insight article.”No no no it's a great thing to do! Very rewarding and helpful! :)

[QUOTE="jim mcnamara, post: 5689101, member: 35824"][USER=310841]@phinds[/USER] – Do you give up yet? This kind of scope problem is daunting. You take a generalized tack, people reply with additional detail. Your plight is exactly why I am loath to try an insight article. You are braver, hats off to you!”Yes, I've notice this in many comment threads on Insight articles. People feel the need to weigh in with their own expertise without much regard to whether or not what they have to add is really helpful to the original intent of the article supposedly being commented on.

I should add that, regarding Lua, they say it is an interpreted language. "Although we refer to Lua as an interpreted language, Lua always precompiles source code to an intermediate form before running it. (This is not a big deal: Most interpreted languages do the same.) " This is different from a pure interpreter, which translates the source program line by line while it is being run. In any case you can read their explanation here.http://www.lua.org/pil/8.htmlBTW it is easy and instructive to write an interpreter for BASIC in C.

[QUOTE="nsaspook, post: 5689143, member: 351035"]Also missing is the language Forth.”To repeat myself:[quote]This was NOT intended as a thoroughly exhaustive discourse. If you look at the wikipedia list of languages you'll see that I left out more than I put in but that was deliberate.[/quote]

[QUOTE="vela, post: 5688952, member: 221963"]Another typo: I believe you meant "fourth generation," not "forth generation."”Also missing is the language Forth.The forth language and dedicated stack processors are still used today for real-time motion control.I had a problem with a semiconductor processing tool this week that still uses a Forth processor to control Y mechanical and X electrical scanning. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/RTX2010https://web.archive.org/web/20110204160744/http://forth.gsfc.nasa.gov/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/RTX2010https://web.archive.org/web/20110204160744/http://forth.gsfc.nasa.gov/

[QUOTE="jedishrfu, post: 5688853, member: 376845"]Scripting languages usually can interact with the command shell that you're running them in. They are interpreted and can evaluate expressions that are provided at runtime.”[QUOTE="jedishrfu, post: 5688853, member: 376845"]Java is actually compiled into bytecodes that act as machine code for the JVM. This allows java to span many computing platforms in a write once run anywhere kind of way.”And of course something like Python has both these traits. But there are plenty of variations for scripting languages.For example some scripting languages are much less handy, e.g. so far as I know, AppleScript can't interact in a command shell, which makes it harder to code in; neither did older versions of WinBatch, back when I was cobbling together Windows scripts with it around 1999-2000; looking at the product pages for WinBatch today, it still doesn't look like this limitation has been removed. Discovering Python after having learned on WinBatch for several years was like a prison break for me.And I also like the example given above by [USER=608525]@David Reeves[/USER] of Lua, a non-interpreted, non-interactive scripting language: "Within a development team, some programmers may only need to work at the Lua script level, without ever needing to modify and recompile the core engine. For example, how a certain game character behaves might be controlled by a Lua script. This sort of scripting could also be made accessible to the end users. But Lua is not an interpreted language."

Yes,, don't give up. Remember the Stone Soup story. You ve got the soup in the pot and we're bringing the vegetables and meat. You've inspired me to write an article too. Jedi

[USER=310841]@phinds[/USER] – Do you give up yet? This kind of scope problem is daunting. You take a generalized tack, people reply with additional detail. Your plight is exactly why I am loath to try an insight article. You are braver, hats off to you!

[QUOTE="vela, post: 5688952, member: 221963"]Another typo: I believe you meant "fourth generation," not "forth generation."”Thanks.

Another typo: I believe you meant "fourth generation," not "forth generation."

[QUOTE="stevendaryl, post: 5688394, member: 372855"]Something that I was never clear on was what made a "scripting language" different from an "interpreted language"? I don't see that much difference in principle between Javascript and Python, on the scripting side, and Java, on the interpreted side, other than the fact that the scripting languages tend to be a lot more loosey-goosey about typing.”One key feature is that you can edit and run a script as opposed to say Java where you compile with one command javac and run with another command java. This means you can't use the shell trick of #!/bin/xxx to indicate that its an executable script.Scripting languages usually can interact with the command shell that you're running them in. They are interpreted and can evaluate expressions that are provided at runtime. The loosey-goosiness is important and makes them more suited to quick programming jobs. The most common usage is to glue applications to the session ie to setup the environment for some application, clear away temp files, make working directories, check that certain resources are present and to then call the application.https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Scripting_languageJava is actually compiled into bytecodes that act as machine code for the JVM. This allows java to span many computing platforms in a write once run anywhere kind of way. Java doesn't interact well with the command shell. Programmers unhappy with Java have developed Groovy which is what java would be if it was a scripting language. Its often used to create domain specific languages (DSLs) and for running snippets of java code to see how it works as most java code runs unaltered in Groovy. It also has some convenience features so that you don't have to provide import statements for the more common java classes.https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Groovy_(programming_language)Javascript in general works only in web pages. However there's node.js as an example, that can run javascript in a command shell. Node provides a means to write a light weight web application server in javascript on the server-side instead of in Java as a java servlet.https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Node.js

[QUOTE="David Reeves, post: 5688593, member: 608525"]Speaking of scripting languages, consider Lua, which is the most widely used scripting language for game development. Within a development team, some programmers may only need to work at the Lua script level, without ever needing to modify and recompile the core engine. For example, how a certain game character behaves might be controlled by a Lua script. This sort of scripting could also be made accessible to the end users. But Lua is not an interpreted language.”This is a good point. "Scripting" is a pretty loose term.

[QUOTE="stevendaryl, post: 5688394, member: 372855"]Something that I was never clear on was what made a "scripting language" different from an "interpreted language"? I don't see that much difference in principle between Javascript and Python, on the scripting side, and Java, on the interpreted side, other than the fact that the scripting languages tend to be a lot more loosey-goosey about typing.”You can read the whole Wikipedia articles on "scripting language" and "interpreted language" but this does not really provide a clear answer to your question. In fact, I think there is no definition that would clearly separate scripting from non-scripting languages or interpreted from non-interpreted languages. Here are a couple of quotes from Wikipedia."A scripting or script language is a programming language that supports scripts; programs written for a special run-time environment that automate the execution of tasks that could alternatively be executed one-by-one by a human operator.""The terms interpreted language and compiled language are not well defined because, in theory, any programming language can be either interpreted or compiled."Speaking of scripting languages, consider Lua, which is the most widely used scripting language for game development. Within a development team, some programmers may only need to work at the Lua script level, without ever needing to modify and recompile the core engine. For example, how a certain game character behaves might be controlled by a Lua script. This sort of scripting could also be made accessible to the end users. But Lua is not an interpreted language.LISP is not a scripting language. On the other hand, LISP is an interpreted language, but it can also be compiled. You might spend most of your development time working in the interpreter, but once some code is nailed down you might compile it for greater speed, or because you are releasing a compiled version for use by others. Now perhaps someone will jump in and say "LISP can in fact be a scripting language,", etc. I would not respond. ;)

[QUOTE="David Reeves, post: 5688215, member: 608525"]One thing I noticed is that although you mention LISP, you did not mention the topic of languages for artificial intelligence. I did not see any mention of Prolog, which was the main language for the famous 5th Generation Project in Japan.[/quote]This was NOT intended as a thoroughly exhaustive discourse. If you look at the wikipedia list of languages you'll see that I left out more than I put in but that was deliberate.[quote]It could also be useful to discuss functional programming languages or functional programming techniques in general.[/quote]And yes I could have written thousands of pages on all aspects of computing. I chose not to.[quote]Since you mention object-oriented programming and C++, how about also mentioning Simula, the language that started it all, and Smalltalk, which took OOP to what some consider an absurd level.[/quote]See above[quote]Finally, I do not see any mention of Pascal, Modula, and Oberon. The work on this family of languages by Prof. Wirth is one of the greatest accomplishments in the history of computer languages.[/quote]Pascal is listed but not discussed. See above[QUOTE="stevendaryl, post: 5688394, member: 372855"]Something that I was never clear on was what made a "scripting language" different from an "interpreted language"? I don't see that much difference in principle between Javascript and Python, on the scripting side, and Java, on the interpreted side, other than the fact that the scripting languages tend to be a lot more loosey-goosey about typing.”Basically, I think most people see "scripting" in two ways. First is, for example, BASIC which is an interpreted computer language and second is, for example, Perl, which is a command language. The two are quite different but I'm not going to get into that. It's easy to find on the internet.[QUOTE="jedishrfu, post: 5688439, member: 376845"]One word of clarification on the history of markup is that while HTML is considered to be the first markup language it was in fact adapted from the SGML(1981-1986) standard of Charles Goldfarb by Sir Tim Berners-Lee:[/quote]NUTS, again. Yes, you are correct. I actually found that all out AFTER I had done the "final" edit and just could not stand the thought of looking at the article for the 800th time so I left it in. I'll make a correction. Thanks.

[QUOTE="stevendaryl, post: 5688394, member: 372855"]Something that I was never clear on was what made a "scripting language" different from an "interpreted language"? I don't see that much difference in principle between Javascript and Python, on the scripting side, and Java, on the interpreted side, other than the fact that the scripting languages tend to be a lot more loosey-goosey about typing.”Others more knowledgable than me will no doubt reply, but I get the sense that scripting languages are a subset of interpreted. So something like Python gets called both, but Java is only interpreted (compiled into bytecode, as Python is also) and not scripted. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Scripting_language

Nice article, [USER=310841]@phinds[/USER]! I would like to point out that some interpreted languages, such as MATLAB, have move to the JIT (just-in-time) model, where some parts are compiled instead of simply being interpreted.Also, Fortran is still in use not only because of legacy code. First, there are older physicists like me who never got the hang of C++ or python. Second, many physical problems are more simply translated to Fortran than other compiled languages, making development faster.

Something that I was never clear on was what made a "scripting language" different from an "interpreted language"? I don't see that much difference in principle between Javascript and Python, on the scripting side, and Java, on the interpreted side, other than the fact that the scripting languages tend to be a lot more loosey-goosey about typing.

Well done Phinds!

One word of clarification on the history of markup is that while HTML is considered to be the first markup language it was in fact adapted from the SGML(1981-1986) standard of Charles Goldfarb by Sir Tim Berners-Lee:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Standard_Generalized_Markup_Language

And the SGML (1981-1986) standard was in fact an outgrowth of GML(1969) found in an IBM product called Bookmaster, again developed by Charles Goldfarb who was trying to make it easier to use SCRIPT(1968) a lower level document formatting language:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/IBM_Generalized_Markup_Language

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/SCRIPT_(markup)

in between the time of GML(1969) and SGML(1981-1986), Brian Reid developed SCRIBE(1980) for his doctoral dissertation and both SCRIBE(1980) and SGML(1981-1986) were presented at the same conference (1981). Scribe is considered to be the first to separate presentation from content which is the basis of markup:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Scribe_(markup_language)

and then in 1981, Richard Stallman developed TEXINFO(1981) because SCRIBE(1980) became a proprietary language:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Texinfo

these early markup languages , GML(1969), SGML(1981), SCRIBE(1980) and TEXINFO were the first to separate presentation from content:

Before that there were the page formatting language of SCRIPT(1968) and SCRIPT’s predecessor TYPSET/RUNOFF (1964):

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/TYPSET_and_RUNOFF

Runoof was so named from “I’ll run off a copy for you.”

All of these languages derived from printer control codes (1958?):

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/ASA_carriage_control_characters https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/IBM_Machine_Code_Printer_Control_Characters

So basically the evolution was:

– program controlled printer control (1958)

– report formatting via Runoff (1964)

– higher level page formatting macros Script (1968)

– intent based document formatting GML (1969)

– separation of presentation from content via SCRIBE(1981)

– standardized document formatting SGML (1981 finalized 1986)

– web document formatting HTML (1993)

– structured data formatting XML (1996)

– markdown style John Gruber and Aaron Schwartz (2004)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Comparison_of_document_markup_languages

and back to pencil and paper…

A Printer Code Story

————————

Lastly, the printer codes were always an embarrassing nightmare for a newbie Fortran programmer who would write throughly elegant program that generated a table of numbers and columnized them to save paper only to find he’s printed a 1 in column 1 and receives a box or two of fanfold paper with a note from the printer operator not to do it again.

I’m sure I’ve left some history out here.

– Jedi

[QUOTE="phinds, post: 5687821, member: 310841"]Yes, there are a TON of such fairly obscure points that I could have brought in, but the article was too long as is and that level of detail was just out of scope.”I think the level you kept it at was excellent. Not easy to do.

This looks like an interesting topic. I hope there will be a focus on which languages are most widely used in the math and science community, since this is after all a physics forum.One thing I noticed is that although you mention LISP, you did not mention functional languages in general. Also, I did not see any mention of Prolog, which was the main language for the famous 5th Generation Project in Japan.I think it would be interesting to see the latest figures on which are the most popular languages, and why they are so popular. The last time I looked the top three were Java, C, and C++. But that's just one survey, and no doubt some surveys come up with a different result.Since you mention object-oriented programming and C++, how about also mentioning Simula, the language that started it all, and Smalltalk, which took OOP to what some consider an absurd level.Finally, I do not see any mention of Pascal, Module, and Oberon. The work on this family of languages by Prof. Wirth is one of the greatest accomplishments in the history of computer languages.In any case, I look forward to the discussion.

[QUOTE="rcgldr, post: 5688122, member: 17595"]No mention of plugboard programming.”The number of things that I COULD have brought in, that have little or no relevance to modern computing, would have swamped the whole article.

[QUOTE="rcgldr, post: 5688122, member: 17595"]"8080 instruction guide (the CPU on which the first IBM PCs were based)." The first IBM PC's were based on 8088, same instruction set as 8086, but only an 8 bit data bus. The Intel 8080, 8085, and Zilog Z80 were popular in the pre-PC based systems, such as S-100 bus systems, ….”Nuts. You are right of course. I spent so much time programming the 8080 on CPM systems that I forgot that IBM went with the 8088. I'll make a change. Thanks.

Some comments:No mention of plugboard programming.http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Plugboard"8080 instruction guide (the CPU on which the first IBM PCs were based)." The first IBM PC's were based on 8088, same instruction set as 8086, but only an 8 bit data bus. The Intel 8080, 8085, and Zilog Z80 were popular in the pre-PC based systems, such as S-100 bus systems, Altair 8000, TRS (Tandy Radio Shack) 80, …, mostly running CP/M (Altair also had it's own DOS). There was some overlap as the PC's didn't sell well until the XT and later AT.APL and Basic are interpretive languages. The section title is high level language, so perhaps it could mention these languages include compiled and interpretive languages.RPG and RPG II high level langauges, popular for a while for conversion from plugboard based systems into standard computer systems. Similar to plugboard programming, input to output field operations were described, but there was no determined ordering of those operations. In theory, these operations could be performed in parallel.

[QUOTE="256bits, post: 5688040, member: 328943"]No choice.You have sent an ASCII 06.Full Duplex mode?ASCII 07 will get the attention for part 2.”Yeah but part 2 is likely to be the alternate interpretation of the acronym for ASCII 08

[QUOTE="phinds, post: 5687860, member: 310841"]AAACCCKKKKK !!! That reminds me that now I have to write part 2.”No choice.You have sent an ASCII 06.Full Duplex mode?ASCII 07 will get the attention for part 2.

[QUOTE="Mark44, post: 5687951, member: 147785"]I thought it was spelled ACK…(As opposed to NAK)“No, that's a minor ACK. MIne was a heartfelt, major ACK, generally written as AAACCCKKKKK !!!

Very well done, thanks phinds for this insight! Judging from this part 1, it gives a very good general picture touching upon many interesting things.

[QUOTE="phinds, post: 5687860, member: 310841"]AAACCCKKKKK !!!”I thought it was spelled ACK…(As opposed to NAK)

[QUOTE="Greg Bernhardt, post: 5687834, member: 1"]Great part 1 phinds!”AAACCCKKKKK !!! That reminds me that now I have to write part 2. Damn !

Great part 1 phinds!

Yes, there are a TON of such fairly obscure points that I could have brought in, but the article was too long as is and that level of detail was just out of scope.

Mainframe assembler's included fairly advanced macro capability going back to the 1960s'. In the case of IBM mainframes, there were macro functions that operated on IBM database types, such as ISAM (index sequential access method), which was part of the reason for the strange mix of assembly and Cobol on the same programs, which due to legacy issues, still exists somewhat today.Self-modifying code – this was utilized on some older computers, like the CDC 3000 series which included a store instruction that only modified the address field of another instruction, essentially turning an instruction into an instruction + modifiable pointer.Event driven programming is part of most pre-emptive operating systems and applications, and time sharing systems / applications, again dating back to the 1960s'.

[QUOTE="anorlunda, post: 5687568, member: 455902"][USER=310841]@phinds[/USER] , thanks for the trip down memory lane. “Oh, I didn't even get started on the early days. No mention of punched card decks, teletypes, paper tape machines and huge clean rooms with white-coated machine operators to say nothing of ROM burners for writing your own BIOS in the early PC days, and on and on. I could have done a LONG trip down memory lane without really telling anyone much of any practical use for today's world, but I resisted the urge :smile:My favorite "log cabin story" is this: In one of my early mini-computer jobs, well after I had started working on mainframes, it was a paper tape I/O machine. To do a full cycle, you had to (and I'm probably leaving out a step or two, and ALL of this is using a very slow paper tape machine) load the editor from paper tape, use it to load your source paper tape, use the teletype to do the edit, output a new source tape, load the assembler, use it to load the modified source tape and output an object tape, load the loader, use it to load the object tape, run the program, realize you had made another code mistake, go out and get drunk.

Thanks Jim. Several people gave me some feedback and [USER=147785]@Mark44[/USER] went through it line by line and found lots of my typos and poor grammar. The one you found is one I snuck in after he looked at it :smile:

[USER=310841]@phinds[/USER] , thanks for the trip down memory lane. That was fun to read.I too started in the machine language era. My first big project was a training simulator (think of a flight simulator) done in binary on a computer that had no keyboard, no printer. All coding and debugging was done in binary with those lights and switches. I had to learn to read floating point numbers in binary.Then there was the joy of the most powerful debugging technique of all. Namely, the hex dump (or octal dump) of the entire memory printed on paper. That captured the full state of the code & data and there was no bug that could not be found if you just spent enough tedium to find it.But even that paled compared the to generation just before my time. They had to work on "stripped program" machines. Instructions were read from the drum one-at-a-time and executed. To do a branch might mean (worst case) waiting for one full revolution of the drum before the next instruction could be executed. To program them, you not only had to decide what the next instruction would be, but also where on the drum it was stored. Choices made an enormous difference in speed of execution. My boss did a complete boiler control system on such a computer that had only 3×24 bit registers, and zero RAM memory. And he had stories about the generation before him that programmed the IBM 650 using plugboards.In boating we say, "No matter how big your boat, someone else has a bigger one." In this field we can say, "No matter how crusty your curmudgeon credentials, there's always an older crustier guy somewhere."

Very well done. Every language discussion thread – 'what language should I use' should have a reference back this article. Too many statements in those threads are off target. Because posters have no clue about origins.Typo in the Markup language section: "Markup language are"Thanks for a good article.