Tell One Wood from Another: Basic Wood Anatomy

Table of Contents

Introduction

About the author

As a long-time woodworker, I enjoy being able to tell one wood from another. In the process of learning how to do that, I’ve developed some knowledge of wood anatomy that I think will interest both biology students and woodworkers. There is an enormous variety of wood-anatomy characteristics; this article discusses a selection to spark interest rather than provide an exhaustive exposition. Because this is an introductory piece and doesn’t cover all of my limited knowledge, I have included references at the end for further reading.

I limit this article to characteristics that are readily discernible to the average woodworker in a shop, garage, or basement with minimal effort and no elaborate equipment. It usually comes as a surprise—even to long-term woodworkers—how much information is available from wood with only a small effort. I want to emphasize that all images in this article were taken of wood I processed in my garage using only a random orbital sander. This is not an elaborate process. See the process.

What this article covers

The most interesting, easily available characteristics are found in the end grain of temperate-zone hardwoods. When you look at the end grain of hardwoods, two primary attributes are of interest: the growth rings (including pore distribution within the rings) and the parenchyma. Pores are the little tubes the tree uses to move sap and nutrients, and parenchyma is another wood tissue that can be arranged in many different ways.

Three steps to identify wood by end grain

Expose

Expose. Clean the end grain so you can see the characteristics clearly. I use a random orbital sander to clean the end grain (the process is shown on my how-to page): clean up end grain.

Examine

Examine. Look at the characteristics with a 10X jeweler’s loupe or take close-up photographs. My camera gives about a 12X view for close-ups.

Use

Use. Compare what you see with reference sources. Links to helpful references are provided at the end of this article.

Annual growth rings and earlywood/latewood

Trees in temperate zones have growing seasons that start in spring and continue through summer and fall. This growth cycle produces annual growth rings composed of earlywood and latewood.

Growth ring count

Fast-growing trees have few growth rings per inch; slow-growing trees have many more. Ring count is a useful characteristic but can vary widely within a species, so it is often not a reliable species identifier.

Types of growth rings (porosity)

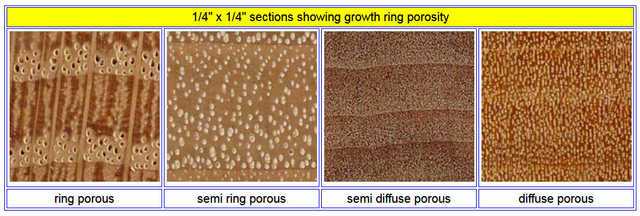

One fundamental attribute is the type of porosity—how pores are arranged relative to growth rings. The main types are:

- Ring-porous: Large earlywood pores that drop off quickly to smaller latewood pores.

- Semi ring-porous: Large earlywood pores that drop off gradually into smaller latewood pores.

- Semi diffuse-porous: Almost uniform pore distribution but with some thinning or smaller pores in latewood.

- Diffuse-porous: Uniform pores throughout the ring.

Rays

Ray height and density

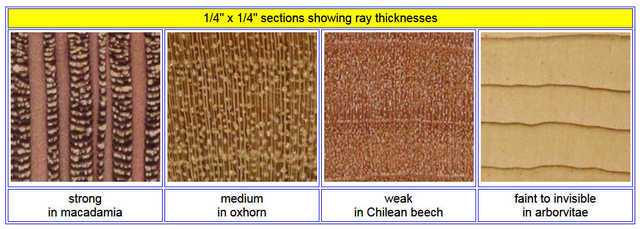

Rays are radial tissues that run from the center of the tree outward toward the bark. Two aspects matter for identification: ray height (size) and ray density (how many per inch). The image below shows categories of ray thickness.

Pore density

Practical categories

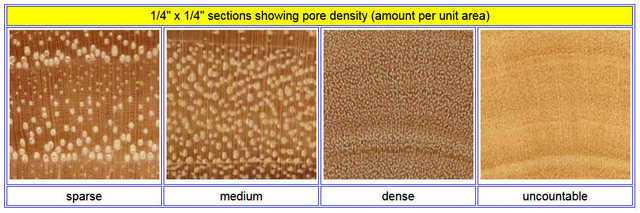

Pore density describes how many pores occur in a unit area. The general categories are shown here. “Uncountable” is a practical label—under a microscope one could count them, but for field identification that’s usually unnecessary.

Pore size

Earlywood vs latewood

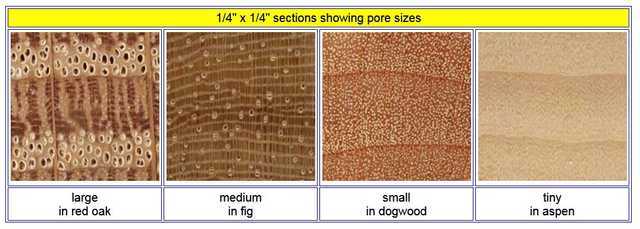

Pore size ranges from too small to see with a 10X loupe up to very large, visible pores (for example, in red oak). Many hardwoods show pore-size variation within a growth ring; the earlywood pores may be much larger than latewood pores. The image below shows a size range.

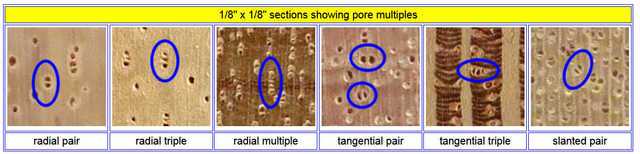

Pore multiples

Orientation and groups

Sometimes pores grow adjacent and share a cell wall; these are called pore “multiples.” Multiples commonly occur in groups of two or three and more rarely up to eight or nine. The orientation of these groups is significant: they can be radial, tangential, or random. The images below illustrate examples. Orientation: the center of the tree is at the bottom and the outside of the tree is at the top; bottom-to-top is radial and left-to-right is tangential.

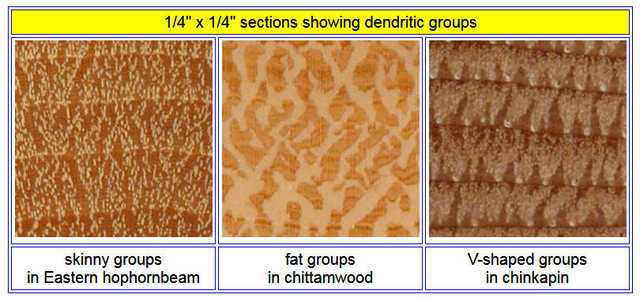

Dendritic groups

Examples

“Dendritic” means tree-like; this pore arrangement loosely resembles branching tree limbs. There are no widely used formal sub-designations for dendritic groups, so the image below shows a convenient set of examples I use for comparison.

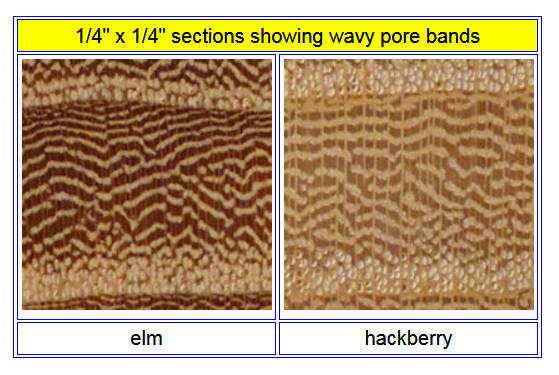

Wavy bands

Typical patterns

Pores may also group into wavy bands—just as the name describes. The image below shows typical wavy bands.

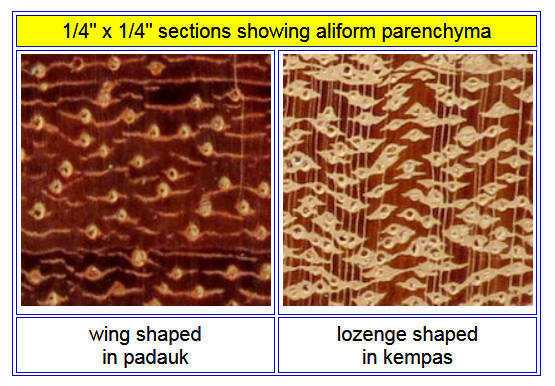

Aliform parenchyma

Wing and lozenge forms

“Aliform” means wing-shaped. Two parenchyma groupings fall into this category. The first is called wing-shaped aliform parenchyma (because it looks solidly wing-shaped); the other is lozenge-shaped. When present, parenchyma cells surround pores and extend to either side in one of the two forms shown here. A well-defined example can resemble a squadron of WWII fighter planes; the lozenge form looks a bit like a cough lozenge.

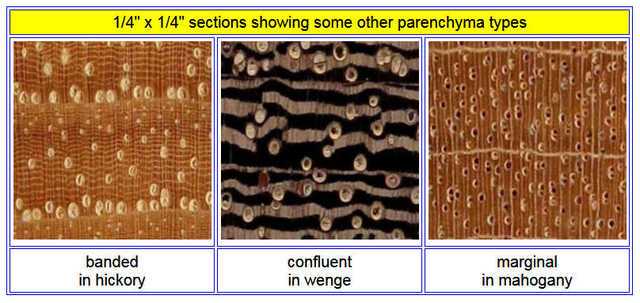

Other parenchyma types

Horizontal arrangements

The images below show several other parenchyma arrangements, often appearing as horizontal lines on an end grain face.

The characteristics above are only a sample—enough to show how identification can rely on combinations of traits.

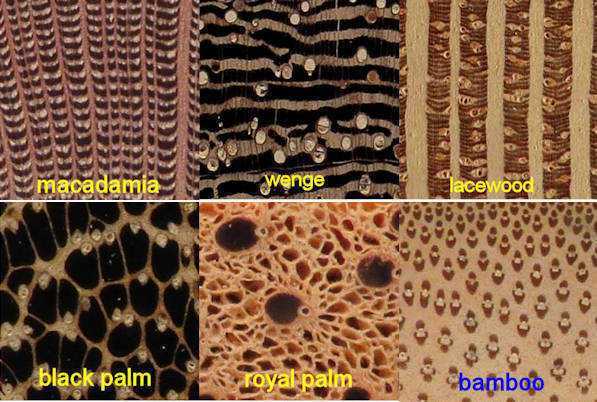

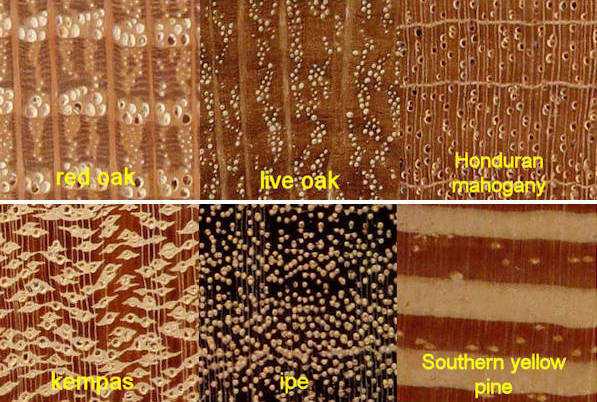

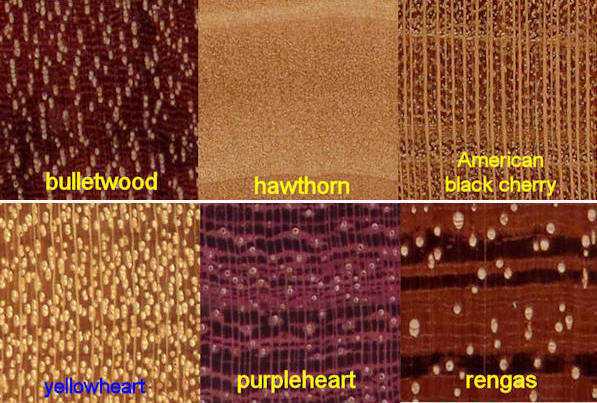

End-grain examples

Small cross-sections

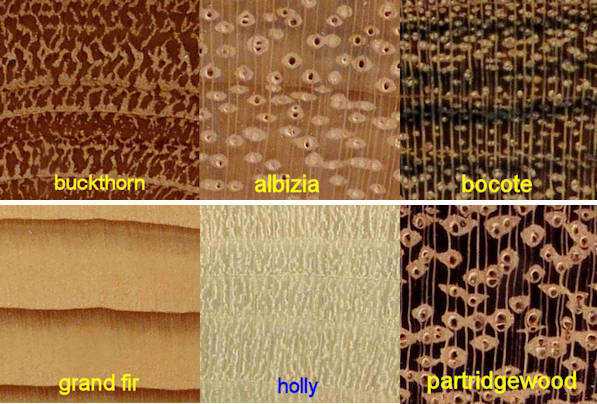

Here are small 1/4″ x 1/4″ end-grain cross-sections that illustrate combinations of the characteristics described above. Once you become familiar with these traits, identifying some woods can be straightforward (though not always). Note the variety in this batch:

References

- Understanding Wood by Bruce Hoadley

- Identifying Wood by Bruce Hoadley

- Wood anatomy — an introduction

- Extensive parenchyma discussion

- Extensive growth ring discussion

- Massive compilation of wood images and discussion (400+ species)

- 50,000+ images of wood anatomy (use botanical names)

Studied EE and Comp Sci a LONG time ago, now interested in cosmology and QM to keep the old gray matter in motion.

Woodworking is my main hobby.

”

I much enjoyed this article. I was reminded of when I was allowed to select a hardwood from the school’s stock from which to build a small book-rack in woodworking class. I chose afromosia. I wish every kid could have such an opportunity. *Sigh*.

”

My understanding is that “shop” doesn’t exist any longer. Kids could hurt themselves on the power tools, or even the hand tools for that matter. Every woodworking show I’ve been to in the last 10 years has been a sea of white hair. Young folks are into electronic stuff (USING it of course, not experimenting with it).

By the way, “afromosia” is the way I spell it for a long time too, but it’s actually “afrormosia”.

”

Bamboo is a monocot in the grass order, yes. So this must be trade defintion?

”

Do you mean designating bamboo as a wood for commercial purposes. It’s just words. It’s like the preposterous names that are made up in the flooring industry for woods that have perfectly good names but which (names) are not euphonious enough for sales people. For example, “Patagonian rosewood” instead of goncalo alves.

Yes, I’m aware of all you (correctly) pointed out. I would add that bamboo is not a wood, it is, like palm (coconut) trees, a grass. Hardness is irrelvant to my article so I did not mention it, along with thousands of other wood fact that are also irrelevant to the article.

”

Sorry, I did not get the point. I missed this sentence midway through the text. “You have to have a reference source or sources to help you understand what you are seeing. I have provided links to a number of those at the end of this article.” So the real subject of the article is not about the identification step, but rather the anatomy data gathering steps.

”

Actually, that’s a good point. In my more extensive expositions I spend more time discussing the pros and cons of some reference sources since they are, as you point out here, at the heart of the whole thing. I just take it for granted that the point of the data identification and collection is ultimately to ID the wood so kind of slid past the fact that I was making an assumption here that may not have been obvious (Although the title of the Insight is a big clue :smile:)

”

Uh … did you not get the POINT of the article?

”

Sorry, I did not get the point. I missed this sentence midway through the text. “You have to have a reference source or sources to help you understand what you are seeing. I have provided links to a number of those at the end of this article.”

So the real subject of the article is not about the identification step, but rather the anatomy data gathering steps.

”

Glad you enjoyed it. There is MUCH more to it that the little bit that’s in the article.

Uh … did you not get the POINT of the article? Identifying wood is what the whole thing is about. People send me wood from all over the country for me to try to ID it, and I run a wood identification sub-forum on the Wood Barter forum. When I buy wood, I rarely trust the seller’s ID unless it’s a very common domestic. Many exotics I can now identify with a quick glance but a lot of them require verification (or re-identification) using the techniques discussed in this article.

I have no idea about the carbon. Never thought about it.

No idea. I just know that even for amazingly tall trees, the sap moves all the way to the top.

No, surprisingly enough the pores of sugar maple are not significantly different than the pores of other maples. Here’s a sugar maple (acer saccharum) end grain on the left and a silver maple (acer saccharinum) on the right.

[ATTACH type=”full” alt=”1576962709865.png”]254518[/ATTACH]

”

”

The pores of sugar maples are critical to syrup production. Are they extra big? Are they clustered near the outer bark so that they freeze/thaw every day in spring?

“By the way, in case you are not aware of it “maple syrup” when it comes out of the tree is essentially indistinguishable from water (it’s about 97 to 98% water and only about 2% sugar).

”

That was fun to read. Thanks for the good article. There is much more to it than I imagined.[/quote]Glad you enjoyed it. There is MUCH more to it that the little bit that’s in the article.

[quote]You label the pictures with the species of tree. How did you know those names? By sight? Did you order a piece by species name?[/quote]Uh … did you not get the POINT of the article? Identifying wood is what the whole thing is about. People send me wood from all over the country for me to try to ID it, and I run a wood identification sub-forum on the Wood Barter forum. When I buy wood, I rarely trust the seller’s ID unless it’s a very common domestic. Many exotics I can now identify with a quick glance but a lot of them require verification (or re-identification) using the techniques discussed in this article.

[quote]The mass of a tree is mostly carbon, fixed from the atmosphere. The tree top needs mass. The roots need mass. Do those pores just move water and nutrients or do they move masses of carbon also? If carbon is produced in the leaves, then it must flow inward then downward, correct?[/quote]I have no idea about the carbon. Never thought about it.

[quote]Trees also need a lot of water. How many liters per day are lifted from the roots to above ground? Is there a kg/sec flow rate for water in the biggest trees?[/quote]No idea. I just know that even for amazingly tall trees, the sap moves all the way to the top.

[quote]The pores of sugar maples are critical to syrup production. Are they extra big? Are they clustered near the outer bark so that they freeze/thaw every day in spring?

“No, surprisingly enough the pores of sugar maple are not significantly different than the pores of other maples. Here’s a sugar maple (acer saccharum) end grain on the left and a silver maple (acer saccharinum) on the right.

[ATTACH type=”full”]254518[/ATTACH]

”

Excellent.

Branches should have growth rings as well.

I suppose one could count the truck rings and compare to the branch rings and find out the ages of each.

The higher up one goes along the truck, or main branch, the number of rings should diminish.

Is there any size or age of truck/branch that it needs to be for “good” wood to work with.

Does the heartwood age in quality as the tree itself ages, the deeper in one goes the better it gets.

Sapwood, I suppose is not too well favoured for woodworking.

”

Heartwood is dead wood so it doesn’t change characteristics particularly with age. Some woods are almost all sapwood so, no, sapwood in general is not a bad thing. Depends on the wood.

I assume you mean “trunk” not “truck”. Branches can start well after a tree has grown a bit so are not useful for telling the age of the tree, just the branch itself and there’s not much point in that. Some small trees/bushes produce very small pieces that are favored by pen makers, so size relevance has to be measured against what you want to do with the wood.

“so one characteristic of interest is how many growth rings does a particular piece of wood have”

Excellent.

Branches should have growth rings as well.

I suppose one could count the truck rings and compare to the branch rings and find out the ages of each.

The higher up one goes along the truck, or main branch, the number of rings should diminish.

Is there any size or age of truck/branch that it needs to be for “good” wood to work with.

Does the heartwood age in quality as the tree itself ages, the deeper in one goes the better it gets.

Sapwood, I suppose is not too well favoured for woodworking.

That was fun to read. Thanks for the good article. There is much more to it than I imagined.

You label the pictures with the species of tree. How did you know those names? By sight? Did you order a piece by species name?

The mass of a tree is mostly carbon, fixed from the atmosphere. The tree top needs mass. The roots need mass. Do those pores just move water and nutrients or do they move masses of carbon also? If carbon is produced in the leaves, then it must flow inward then downward, correct?

Trees also need a lot of water. How many liters per day are lifted from the roots to above ground? Is there a kg/sec flow rate for water in the biggest trees?

The pores of sugar maples are critical to syrup production. Are they extra big? Are they clustered near the outer bark so that they freeze/thaw every day in spring?

”

Nice article.

I have read one of your references, the “Understanding Wood” book and was really impressed with it.

I like wood with unusual grain (seen longitudinally), like curly maple and related effects with other names.

I realize that is viewing the wood from another axis and think it is due to waviness in the way the longitudinal components are laid down, but don’t fully understand it.

Any insights on that? (Maybe another Insight)

”

[URL=’http://www.hobbithouseinc.com/personal/woodpics/_g_C.htm#curlyfigure’]curlyfigure[/URL]

Nice article.

I have read one of your references, the “Understanding Wood” book and was really impressed with it.

I like wood with unusual grain (seen longitudinally), like curly maple and related effects with other names.

I realize that is viewing the wood from another axis and think it is due to waviness in the way the longitudinal components are laid down, but don’t fully understand it.

Any insights on that? (Maybe another Insight)