Animal Speed Scaling: Body-Lengths per Second Across Sizes

Table of Contents

Introduction

In a recent American Journal of Physics issue, I read an interesting paper by Nicole Meyer-Vernet and Jean-Pierre Rospars examining the top speeds of organisms across a huge range of sizes, from bacteria to blue whales. They found that the time it takes an animal to traverse its own body length is, to zeroth order, almost independent of mass across roughly 21 orders of magnitude. The authors derive a simple scaling argument and an order-of-magnitude estimate that explains this remarkable observation.

Before summarizing their argument, I give a brief overview of scaling arguments and why they are a powerful tool for extracting broad behavior from complex systems.

Scaling Arguments

There is a common false dichotomy in physics: either you give a quasi-philosophical, descriptive explanation, or you present rigorous formulae that require long study. Between these extremes sits a very useful middle ground: scaling arguments.

A scaling argument is a step above a Fermi calculation. In a Fermi calculation we estimate values of parameters and multiply them to get an order-of-magnitude result, typically ignoring constants of order unity. With a scaling argument we ask how a dependent quantity changes as an independent quantity is varied, we neglect dimensionless coefficients, and we focus on limiting behavior and power laws.

Square–Cube Law

A classic example is the Square–Cube Law, known since Galileo and highlighted in Haldane’s essay On Being the Right Size. If an object is scaled by a factor of two in every linear dimension, its volume and mass increase by 2^3 = 8, while its cross-sectional area increases only by 2^2 = 4. Thus as organisms (or structures) get larger, mass grows faster than the area available to support it, so weight becomes more significant relative to strength.

Another illustrative case is terminal velocity: drag scales with cross-sectional area (∝ radius^2, or roughly mass^(2/3) for similar shapes), while weight scales with volume (∝ radius^3, or mass^1). Haldane describes the practical consequence:

You can drop a mouse down a thousand-yard mine shaft; and, on arriving at the bottom, it gets a slight shock and walks away, provided that the ground is fairly soft. A rat is killed, a man is broken, a horse splashes.

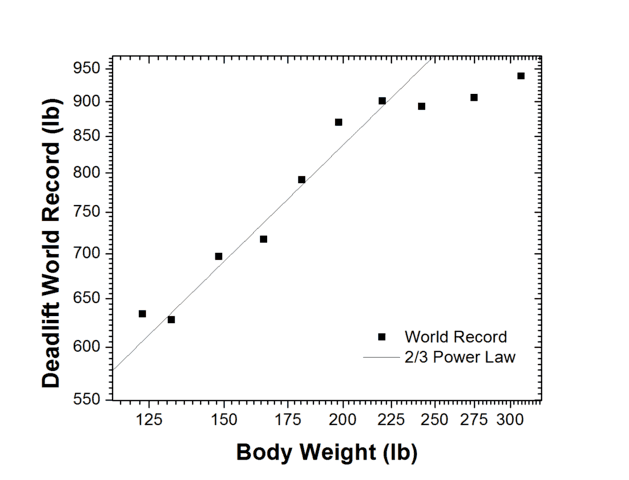

Example: Deadlift Records and the 2/3 Power Law

To test a simple scaling prediction, I assumed that a human’s cross-sectional area scales as the square of height (or roughly as mass^(2/3)). If peak strength scales with cross-sectional area, then peak strength should scale as mass^(2/3).

I looked up the deadlift world-records for men across weight classes. The records follow the 2/3 scaling law reasonably well from the smallest lifters up to about 220 lb. Above that weight the scaling breaks down because competitors tend to have more fat without a proportional increase in muscle. A power-law fit yields a best-fit exponent of 0.67 ± 0.05, consistent with the 2/3 prediction. (I use this example to show how a simple scaling argument can provide a useful prediction for a complex biological system.)

The Animal Speed Paper: Main Observation

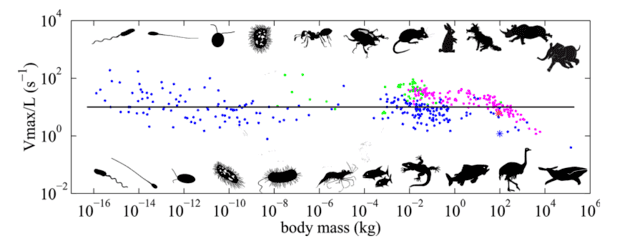

The central observation of Meyer-Vernet and Rospars is summarized in a single figure: they plot how many body-lengths an animal can cover per second as a function of mass. For example, Usain Bolt can cover roughly six of his own heights per second, while elite swimmer Florent Manaudou covers about one body length per second in the pool.

Their dataset spans organisms from bacteria (≈ 10-16 kg), which swim with rotating flagella, up to whales (≈ 105 kg) that undulate their bodies — covering about 21 orders of magnitude in mass. The authors find that the traversal frequency (body-lengths per second) is roughly independent of mass across most of this range. There is scatter, and some systematic deviation at the largest sizes, but the best-fit slope is around −0.06, close to zero, so the zeroth-order conclusion stands: traversal frequency is nearly mass-independent.

Why a Mass-Independent Frequency Emerges

The authors aim to explain why body-lengths-per-second is roughly constant and to estimate its magnitude to within about an order of magnitude.

They identify three broadly shared features of motile organisms:

- Density: Most life is water-like and roughly buoyant, with density ≈ 1 kg/L.

- Muscle stress: Muscle force per unit area, determined by protein interactions, is similar across taxa. The paper cites a characteristic muscle stress of roughly 20,000 N/m2.

- Metabolic power per unit mass: Related to heat-transfer and physiology. The paper adopts a value on the order of 2 W per kilogram of muscle (the article cites controversy in the literature about the precise value; the derivation uses an order-of-magnitude estimate).

Using dimensional analysis, they combine these quantities to obtain the units of frequency (1/s), yielding an estimate for the maximum traversal frequency. The result is, to order of magnitude:

Maximum speed / body length ≈ (metabolic power per mass × density) / (muscle stress) ≈ 10 body lengths per second

This expression is essentially independent of body mass (zeroth power of mass), which is consistent with the data. The claim is not that every organism attains 10 body-lengths/s, but that most organisms fall within a factor of ten around this estimate (i.e., roughly between 1 and 100 body-lengths/s in the extremes of their model). The paper also offers mechanical reasoning about how the energy required to move appendages (flagella, legs, tails) leads to similar characteristic frequencies. They note a weak negative scaling for the largest organisms and argue that the mass-independent scaling applies up to body sizes of about 1.4 m.

Conclusion

I enjoyed this paper because it takes a striking empirical pattern and explains it with simple, broadly applicable physical ideas: scaling analysis, dimensional reasoning, and order-of-magnitude estimates. It is striking that three shared physiological features lead to a nearly universal locomotion frequency across so many orders of magnitude in mass.

Click here for the forum comments.

Ph.D. McGill University, 2015

My research is at the interface of biological physics and soft condensed matter. I am interested in using tools provided from biology to answer questions about the physics of soft materials. In the past I have investigated how DNA partitions itself into small spaces and how knots in DNA molecules move and untie. Moving forward, I will be investigating the physics of non-covalent chemical bonds using “DNA chainmail” and exploring non-equilibrium thermodynamics and fluid mechanics using protein gels.

The additional constraint they apply on large animals, which oscillate their length L with some frequency f, is that there is a maximum angular acceleration that can be applied. The maximum torque depends on the muscle fibre force, the cross sectional area, and the length of the "lever arm," while the moment of inertia depends on the density, volume, and distribution of the shape. Comparing torque to moment of inertia they get a second-order ODE for the angle of the oscillating part (tail, leg, whatever) over time, which they integrate to find the time required to oscillate to a certain angle. This gives them an *absolute* maximum speed. So they compare their "maximum speed per body length" to the "absolute maximum speed" and solve for the body length at which the two are equal.

Hope that made sense. Picturing a cheetah, they are about 1.4 meters long, and plugging in their values for the "maximum speed" you actually get a fast jog, about 4 m/s. If you apply 10 bodies/second to 1.4 meters, you get 14 m/s=50 km/h which is about half a cheetah's top speed.I wondered, isnt square-cube law only affects acceleration? Maintaining a speed at basic means acceleration has to overcome drag force of water or air. With bigger body, the drag force is higher, but not so high as the mass. With theese assumptions i dont find it strange that speed is rather independent from mass.

Wow. How did I miss this one? This is a great article. Thanks for writing it.

Some specific examples across species would help understanding this topic!

“I couldn’t help but be reminded of another similar study – the one finding (statistically) constant time of emptying the bladder across five orders of magnitude of animal mass (what the authors dubbed ‘the law of urination’):

[URL]http://arxiv.org/abs/1310.3737[/URL]”

My father is a urologist and I went to a conference he organized and talked about this paper! The model they came up with doesn’t quite make sense given their data. They read too much into their measured scaling, when I’m sure the error bars on it are huge to the point of making it insignificant. There was another paper using dimensional analysis to find a better model.

[quote]The second is that all motility is caused by the contraction of muscle proteins that have a similar structure across all life-forms.[/quote]

Certainly all animals use the same types of muscle proteins for movement, but bacteria and other motile single-celled organisms use very different types of proteins for motion (for example, actinomyosin contraction in animals is driven by ATP hydrolysis whereas flagella are powered by the movement of protons across a membrane). Of course, the authors’ estimate relies solely on considering the mechanical properties of proteins in general, so it seems to not be so dependent on how these proteins generate motion, just on the fact that proteins are generating force.

I couldn’t help but be reminded of another similar study – the one finding (statistically) constant time of emptying the bladder across five orders of magnitude of animal mass (what the authors dubbed ‘the law of urination’):

[URL]http://arxiv.org/abs/1310.3737[/URL]

Congrats [USER=569939]@klotza[/USER] on this Insight making it to the first page of Reddit! Well deserved!

This 1.4m “dominance zone” I guess I would call it keeps nagging at me. I’d be grateful for any elaborations you could offer there… as I’m not able to access the paper.

Hi everybody, this is the author. I hope enjoy what I have written, and let me know if anything needs clarification.

All I know is that ants and beetles appear to be on the image.

Nice article! Adrian Bejan talks about this kind of thing in his book Design in Nature. He even extends the reasoning to the evolution of technology, like cars and planes. His idea is that the world is organized by flow. That structures that increase the flow of matter are selected.This is related to the idea that energy from the sun flows through the surface of the earth (coming in as yellowish light and leaving as infrared), and matter forms cycles (like the water cycle, the carbon cycle, etc.).

My source is mainly experience from when I used to be into powerlifting. However this paper also asserts the claim, with better data.http://jap.physiology.org/content/89/3/1061.short"Although it is possible that larger lifters activate less of their contractile filaments, the more likely explanation for their reduced strength per cross-sectional area is that they carry more of their body mass as noncontractile tissue. "

I'm wondering, is the same true for animals like spiders that don't use the same mechanisms to move as most animals do?

I'm slightly confused about the title of this… like I understand most parts but it just seems like you are saying all animals have the same rate at which they can move there own body length. Would just like clarifying on that

You said, "Above that it breaks down because the lifters generally get fatter without getting much more muscular."; do you have a source on that?

"metabolic rate per unit mass … 2 kilowatts per kilogram of muscle. The paper doesn’t really explain where this comes from, citing controversy in the literature" Yes. This is controversial, but the argument is usually between a power law with an exponent of 2/3 or 3/4. A fascinating paper (The fourth dimension of life: fractal geometry and allometric scaling of organisms. West GB, Brown JH, Enquist BJ. Science. 1999 Jun 4;284(5420):1677-9) will definitely be interesting to readers of this post.

The additional constraint they apply on large animals, which oscillate their length L with some frequency f, is that there is a maximum angular acceleration that can be applied. The maximum torque depends on the muscle fibre force, the cross sectional area, and the length of the "lever arm," while the moment of inertia depends on the density, volume, and distribution of the shape. Comparing torque to moment of inertia they get a second-order ODE for the angle of the oscillating part (tail, leg, whatever) over time, which they integrate to find the time required to oscillate to a certain angle. This gives them an *absolute* maximum speed. So they compare their "maximum speed per body length" to the "absolute maximum speed" and solve for the body length at which the two are equal.Hope that made sense. Picturing a cheetah, they are about 1.4 meters long, and plugging in their values for the "maximum speed" you actually get a fast jog, about 4 m/s. If you apply 10 bodies/second to 1.4 meters, you get 14 m/s=50 km/h which is about half a cheetah's top speed.

Thanks for the insight! This is a very interesting topic for me, but I must say I was quite skeptical until I realized this is about TOP speed, more in line with physical limits. I'm fairly certain mobility is advantageous across most forms of beings so It certainly makes sense to me that evolution has pushed towards the limits across all scales.

Nice article @klotza!