Astrophotography Guide: Equipment, Exposure & Processing

Table of Contents

Complete Series

- Part 1: Introduction Astrophotography

- Part 2: Intermediate Astrophotography

- Part 3: Advanced Astrophotography

Level 2: I know how to use a camera — what do I need to know for astrophotography?

Image processing, optics, and sensor basics

Image-processing methods to reduce background and noise become much more important for astrophotography. It also helps to understand basic optics (f-number, Seidel and chromatic aberrations, angular field of view, Airy disc) and some digital-sensor concepts (Bayer filter, analog/digital signal processing, and noise). You don’t need to master everything, but greater familiarity will speed your learning.

Equipment & setup

Camera settings & tripod

Set your camera to fully manual (including focus) and use a sturdy tripod. Because modern sensors are very sensitive, blur, vibration, and lens aberrations are easier to see. The overall goal is to give your stacking program a series of images taken under identical conditions — so disable any in-camera processing: no HDR, no long-exposure noise reduction, no adaptive exposure, no automatic gain, etc. Also disable any built-in stabilization when the camera is on a tripod. If your camera has a mirror-up setting, use it; live view can also help if the shutter does not re-engage between frames.

Mirrorless vs DSLR

Mirrorless cameras avoid mirror-induced shake, but many divert a fraction (up to about 1 stop) of incident light to the electronic viewfinder, reducing throughput compared with some DSLRs.

Essentials to bring

- Second charged battery

- Shutter release cable or programmable intervalometer (many cameras have this built-in)

- Small flashlight or red light for LCDs

- Lens wipes / microfiber cloth

- Folding chair

- Extra memory cards

Once you are set up and happy with exposure settings, avoid changing them — stacking algorithms work best when all frames share identical settings.

Safety & field tips

You will often be outside at night for several hours, so dress for dropping temperatures and bring bug spray. Night vision takes a few minutes to develop — once it does, avoid bright lights. Be aware of your surroundings: stay on your property or obtain permission before setting up. Animals (cats, rabbits, raccoons, possums, skunks, mink, deer, coyotes) are active at night and can surprise you — be cautious.

Focus drift

Temperature changes or lens element settling can cause focus drift. Check focus every ~20 minutes — focus error cannot be tolerated. Live view helps for precise and rapid focusing. When temperature fluctuates, lenses can fog with condensation; keep lens wipes handy.

Finding objects

Sky positions are specified in declination and right ascension (DEC/RA). Converting DEC/RA to local horizon coordinates (azimuth/elevation) requires date/time and some math, so many astrophotographers prefer “star hopping”: use bright stars to roughly aim, acquire a test frame, then fine-tune. Useful online tools:

Processing & Workflow

Log scales vs. linear sensors

If you are used to log scales (f-numbers, EV), thinking in stellar magnitudes is straightforward. A one-unit change in apparent magnitude corresponds to approximately ±1.3 EV. This matters for dynamic range: digital sensors are linear, while human vision is approximately logarithmic, so sensors have a much more restricted dynamic range than our eyes.

Adding bits (8-bit vs 14-bit) does not make a camera more sensitive; it increases tonal resolution by subdividing the same intensity range into more bins, lowering the noise floor and enabling retrieval of low-intensity data. RAW files allow you to “push” exposures via tone mapping — essentially a nonlinear remap that brings shadow or highlight detail into the midtones. Tone mapping is a form of image compression: wide tonal ranges in RAW are compressed to the limited range of display formats (typically 8 bits/channel).

Astrophotography commonly deals with dynamic ranges of 100,000:1 or more — beyond even 16-bit capture. Learning how to compress a high-SNR stacked image (16-, 32-, or even 48-bit/channel) into a visually balanced 8-bit/channel image is essential. Remember: most displays show 8 bits/channel; a few specialized displays support 10 bits/channel.

Choice of lenses

All lenses can be used for astrophotography. Older manual-focus lenses are often inexpensive and excellent starting points. Prefer lenses with a large entrance pupil. Wide-angle lenses excel for meteors and large starfields (like the Milky Way) and relax star-trail limits. Normal (standard) lenses are good for medium-sized regions; fast normal lenses (e.g., 50mm f/1.4) can be inexpensive and perform well. Telephoto lenses provide high magnification but are more sensitive to vibration and require shorter per-frame exposure times.

Ensuring optimal optical performance

Most lenses cannot be used at their absolute widest apertures without showing off-axis aberrations. Often, stopping down 1/3 to 1 stop reduces coma, field curvature, chromatic aberration, and flare. Because stopping down reduces throughput, alternatives are to shoot wide open and crop objectionable margins, or deliberately stop down for artistic effects (e.g., diffraction “sunstars” around bright stars after stacking).

Seeing (atmospheric turbulence)

“Seeing” — clear-air turbulence caused by temperature-driven refractive-index variations — limits image quality. It is commonly modeled as a slowly moving, spatially varying lens. Seeing can vary seasonally and with object elevation (objects near the horizon suffer worse seeing). Use local seeing forecasts (for example ClearDarkSky) when planning deep imaging sessions. For typical camera lenses the entrance pupil is small, so seeing is less limiting than for large telescopes.

Background noise and light pollution

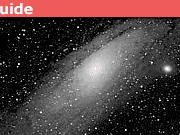

The night sky is not truly dark: light pollution from terrestrial sources raises the background. Light pollution is worse near population centers, but stacking and post-processing techniques can greatly reduce its impact.

Exposure time limits (how long can I expose for?)

Stars move at about 15 arc-seconds per second (360° per sidereal day). The maximum exposure time per frame to avoid noticeable star trailing depends on focal length (35mm equivalent) and DEC. A common heuristic is the “500 rule”: 500 ÷ (focal length in mm) ≈ maximum exposure in seconds. You may see “600 rule,” “400 rule,” etc.; these are crude. Test with a few exposure times and inspect results. I typically use a stricter limit (closer to a “200 rule”) depending on pixel size and seeing. If you want star trails, ignore these limits and leave the shutter open as long as desired (see “Special topics” below).

Point Spread Function (PSF)

PSF is a key metric. In practice the PSF often approximates a Gaussian (due to seeing and processing) rather than an Airy disc. A diffraction-limited PSF can be calculated from optics, but real-world PSFs are usually much larger due to seeing. For example, a 400mm f/2.8 lens might have a theoretical PSF FWHM ≈ 1.7 μm (≈0.88″), but my measured FWHM is typically ~3.6 pixels (≈10× the diffraction limit) and increases slightly after processing to ≈4.3 pixels due to dynamic-range compression.

Image stacking: concepts

Stacking is more than per-pixel averaging or selecting brightest pixels. Stacking combines many low-SNR images to create a high-SNR result by taking advantage of statistical properties of the stochastic background (airglow and scattered light approximately follow Poisson statistics). More frames reduce this noise component.

Data workflow

I commonly acquire large amounts of data (e.g., 50 GB/night). My workflow:

- Transfer images from the camera card to local drive.

- Register images (first step in stacking) and delete poor frames (thresholding based on PSF FWHM).

- Move remaining images to an external drive for long-term storage; run stacking from that drive.

How to get the best stacking results

Use RAW images to maximize dynamic range. Individual frames should often appear underexposed when linearly scaled to 8-bit — this avoids clipping bright stars. Lower ISO values usually yield higher per-frame dynamic range, better color, lower background noise, and less posterization. Avoid clipping at both high and low ends (clipping is permanent signal loss).

Example single-frame results (15 s exposures, my camera + lens). These are raw measurements (background average, background s.d., star average, star s.d., resulting SNR, and the brightest non-clipped star magnitude):

| ISO | Background (avg) | Background (s.d.) | Star avg | Star s.d. | SNR | Brightest mag. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 160 | 698 | 36 | 1101 | 158 | 1.58 | 7.95 |

| 500 | 3517 | 170 | 4542 | 272 | 1.29 | 9.51 |

| 800 | 6088 | 243 | 7648 | 333 | 1.26 | 10.87 |

I obtained stellar magnitudes from SIMBAD. These measurements suggest the best SNR for my setup comes from ISO 160 (as expected), though in practice I sometimes prefer ISO 500 when stacked backgrounds are near-black to avoid processing artifacts.

Tone mapping

Think of film characteristic (H&D) curves: position the background near the “toe” and the brightest stars near the “shoulder,” and set gamma as high as possible to separate low-intensity background from features of interest. In short: map shadows and highlights thoughtfully to preserve detail.

Specialized astrophotography cameras and filters

Commercial camera sensors’ spectral response often does not match astrophysical emission (e.g., H-alpha nebulosity). Two approaches:

- Modify a regular camera (remove some sensor/IR filters) to increase red/UV throughput — note lenses are often poorly corrected in far-red/UV, so add spectral filters to control chromatic aberration unless using reflective optics.

- Use a dedicated astronomical camera — scientific-grade, often cooled and monochrome, with higher QE and narrower spectral control.

Special topics

Star trails

For star trails you commonly stack frames differently: leave the shutter open or take frequent long frames and then project the brightest pixel values across the stack to produce continuous trails. Acquire 2–3 hours or more for dramatic trails. Wide-angle lenses are ideal for composition and for including terrestrial foregrounds. You can change ISO during the run to create a “head” or “tail” effect on trails. You can also interrupt a trails run to take a block of stationary frames for normal stacking and then composite the processed snapshot into the trails image.

Timelapse

Similar to star trails but use shorter exposures (e.g., a few times the no-trail limit). I often use 1-minute exposures on a 15mm f/2.8 lens. Use an intervalometer with no delay between frames and run for 5–6 hours, then assemble frames into a movie. Airplane streaks and satellites often appear and can add interesting motion.

Imaging the Sun

Do not image the Sun without proper filtration. Use a reflective ND filter >5 or purpose-built solar filters (e.g., narrowband etalons for H-alpha or Ca K) to protect equipment and eyes.

Imaging meteors

Wide-angle lenses and wide-open apertures with high ISO are best to capture faint meteors. Adjust exposure times and ISO to local conditions.

Imaging satellites

Very short shutter times (1/1000–1/2000 s) remove motion blur. Use resources like Heavens-Above to plan passes — learn the satellite’s path and expected magnitude. For bright satellites, set ISO with a comparison star; mirror-up isn’t necessary for very short exposures. Ensure your mount/tripod can slew smoothly if you plan to track fast-moving objects.

Useful exercises

1. Photographing airplanes

Daytime high-altitude aircraft practice focusing and exposure and helps prepare you to track satellites at night.

2. Photographing Jupiter’s moons

Jupiter’s four Galilean moons are visible in binoculars and with a moderately fast lens. Photograph Jupiter on consecutive nights or hours apart and you can resolve moon orbital motion.

3. Crescent Moon

The crescent moon is a challenge: it’s only visible for a short window and appears low in the sky. Try varying shutter speeds and ISO to minimize seeing; also try deliberate overexposure to capture light on the unilluminated portion (earthshine).

Up Next: Part 3: Advanced Astrophotography

PhD Physics – Associate Professor

Department of Physics, Cleveland State University

Great series! Part 3 coming later today!

Thank you so much. I hope to return to your articles some day in the future if I get to take up that hobby. They make a great tutorial.(Now, I live on a sailboat riding at anchor. Night photography, with or without a telescope, is hopeless. But some day I expect that I'll have to move onto fast land, and astrophotography is on my bucket list.)