Types of Programming Languages: Uses, Examples, Overview

In this Insights Guide, the focus is entirely on types of languages, how they relate to what computers do, and how they are used by people. It is a general discussion and intended to be reasonably brief, so there is very little focus on specific languages. Please keep in mind that for just about any topic mentioned in this article, entire books have been written about that topic vs. the few sentences here.

The primary focus is on:

- Machine language

- Assembly language

- Higher-level languages

There is also discussion of:

- Interpreters (e.g. BASIC)

- Markup languages (e.g. HTML)

- Scripting languages (e.g. JavaScript, Perl)

- Object-oriented languages (e.g. Java)

- Integrated Development Environments (e.g. the .NET Framework)

Table of Contents

Machine Language

Computers work in binary and their native language is strings of 1’s and 0’s. In my early days, I programmed computers using strings of 1’s and 0’s input to the machine by toggle switches on the front panel. You don’t get a lot done this way, but fortunately I only had to input a dozen or so instructions to create a tiny “loader” program. That loader would then read in more powerful programs from magnetic tape.

It was possible to do more elaborate things directly via toggle switches, but remembering exactly which string of 1’s and 0’s represented which instruction was painful and error-prone. So, very early on the concept of assembly language arose.

Assembly Language

Assembly language represents each machine instruction’s string of 1’s and 0’s by a human-readable word or abbreviation, such as “add” or “ld”. These human-readable statements are translated to machine code by a program called an assembler.

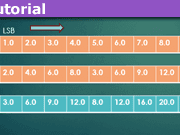

Assemblers typically have an exact one-to-one correspondence between each assembly statement and the corresponding machine instruction. That differs from high-level languages, where a single high-level statement may generate dozens of machine instructions. Using assembly is effectively programming the machine directly: you use words instead of raw binary, but you still control registers, I/O, memory layout, and data flow explicitly—things not directly exposed in most higher-level languages.

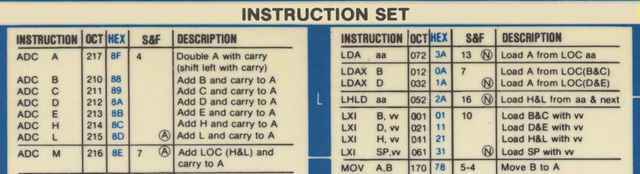

Every CPU family has its own instruction set and therefore its own assembly language. That can be frustrating when moving to a new machine: a mnemonic like “load” may become “ld” or “mov” on another CPU, and instruction sets differ in what operations they support. That can force you to focus on machine-specific implementation details instead of concentrating on the algorithm you want to implement.

The advantage of assembly is precise control and maximum opportunity for optimization, which is useful for things like device drivers or extremely performance-critical code. The downside is that you must specify every detailed step the machine should perform. For example, an algebraic statement such as:

A = B + COSINE(C) – D

…must be decomposed into many explicit steps, for example (pseudo-assembly):

- Load memory location C into register 1

- Call subroutine “Cosine” (result back in register 1)

- Load memory location B into register 2

- Add registers 1 and 2 (result in register 1)

- Load memory location D into register 2

- Subtract register 2 from register 1 (result in register 1)

- Save register 1 to memory location A

And that’s a very simple algebraic statement—you must specify each step in the correct order, without mistakes. To illustrate, here’s a small portion of an 8080 instruction guide (octal and hex forms were often used during debugging):

Because of the tediousness of assembly programming, compilers were developed.

Compilers and Higher-level Languages

Compilers remove the need to program the minutiae of registers and memory locations. They let you concentrate on the algorithm you want to implement rather than machine-level details. Compilers translate higher-level, more human-like statements into machine code. The downside is that when something goes wrong, mapping a high-level statement back to the machine-level behavior can be more difficult than with assembly or machine code; sophisticated debuggers are therefore essential.

As high-level languages add abstraction, the gap between what the programmer writes and what the machine executes increases. Modern programming environments reduce this pain: you often work inside an Integrated Development Environment (IDE) that includes compilers, debuggers, linkers, and other tools to help find and fix errors.

Early high-level languages included:

- Fortran (early 1950s)

- Autocode (1952)

- ALGOL (late 1950s)

- COBOL (1959)

- LISP (early 1960s)

- APL (1960s)

- BASIC (1964)

- PL/1 (1964)

- C (early 1970s)

Subsequent notable languages include:

- Ada (late 1970s / early 1980s)

- C++ (1985)

- Python (late 1980s)

- Perl (1987)

- Java (early 1990s)

- JavaScript (mid-1990s)

- Ruby (mid-1990s)

- PHP (1994)

- C# (2002)

There were many others with varying degrees of impact. One lesser-known example is JOVIAL (Jules’ Own Version of the International Algorithmic Language), which I mention mainly because of the amusing name.

Special note about C: C became widely used and influenced many later languages. Operating system kernels (Unix, Windows, and earlier Apple systems) have significant portions written in C, with some assembly for device drivers. By design, C is closer to assembly than most high-level languages. Java is more widely used today in some areas, but C remains popular.

Interpreters, Scripting, and Command Languages

Interpreters differ from assemblers and compilers: rather than generating object code to run later, an interpreter translates and executes statements on the fly, one statement (or even part of a statement) at a time. The low-level details such as register use are hidden from the programmer.

The obvious trade-off is performance: interpreted code is typically slower than compiled code. However, modern hardware often makes speed less of an issue, while the advantages of interpreters—faster edit-test cycles and interactive debugging—remain important. You can frequently pause execution, modify variables or code, and resume interpretation.

Because interpreters often execute statements sequentially, some syntax errors only appear at the moment a specific path is interpreted. Assemblers and compilers process source code more fully before execution and can detect many syntax errors earlier. Some interpreters perform a pre-execution pass to catch errors ahead of time.

BASIC was the first widely used interpreted language. JavaScript is commonly interpreted in the browser (though modern engines may include just-in-time compilation). Another important scripting form is the command script or shell script (for example, DOS batch files or Unix shell scripts). Perl was historically popular for system administration and remains in use today because of its cross-platform support and versatility.

Markup Languages

The most widely used markup language is HTML (HyperText Markup Language). HTML defines rules for encoding documents in a format that a browser can read and present. Although people sometimes call HTML “code,” it is technically data that describes structure and presentation rather than executable machine code.

Markup differs from compiled or interpreted programming languages in that markup does not produce object code nor directly execute. Instead, a program (a browser) reads markup and uses it to construct a document or UI. Cascading Style Sheets (CSS) complement HTML by describing presentation rules. HTML5 and CSS extend the capabilities of web pages, but detailing them is beyond this article.

Procedural code (for example, JavaScript) can be embedded in HTML. The browser treats JavaScript as a program to execute to make pages dynamic and interactive. Server-side procedural code (for example, PHP) can modify what is served to the client. JavaScript is typically interpreted but modern engines also compile it to machine code at runtime for performance.

Integrated Development Environments (IDEs)

Modern programming often takes place inside an IDE—an environment that bundles an editor, compiler, debugger, linkers, project management tools, and other facilities such as version control and object/class browsers. Many IDEs also provide drag-and-drop UI construction, automatic generation of boilerplate code, and language-integrated tools that hide low-level details from the developer.

The line between a full IDE and a simpler environment is fuzzy, but IDEs in their modern form evolved significantly in the 1980s and 1990s and have continued to grow more powerful since then.

To summarize, the basic types of computer languages are:

- Assembler

- Compiler-based (higher-level)

- Interpreted

- Scripting

- Markup

- Database (not discussed in this article)

Within those categories there are other important paradigms—most notably object-oriented and event-driven programming—which influence how programs are designed and executed.

Object-oriented Languages

Traditional compiled high-level languages rely on subroutines and procedures. Object-oriented programming (OOP) organizes data and code into objects that combine state and behavior, enabling different design and reuse patterns.

C++ added object-oriented features to C but doesn’t require their use; you can write procedural C++ code. Java, by contrast, enforces object orientation: everything is part of an object. C# was created by Microsoft as a strongly object-oriented language; historically it was closely tied to Microsoft platforms, though the ecosystem has evolved since its introduction.

Objects and OOP provide flexibility and extensibility, but exploring them in depth is beyond this article’s scope.

Event-driven Programming

Traditional procedural programs follow a linear or explicitly controlled flow. Event-driven programs, common in GUI and interactive environments, respond to external events such as mouse clicks, key presses, or messages from other parts of the system. Event-driven design is built into many modern IDEs and operating systems and is essential for highly interactive, windowed applications.

Like object orientation, event-driven design has strengths and trade-offs; covering those thoroughly would require a separate discussion.

Generations of Languages

Literature sometimes groups languages into “generations.” The categorization is not universally useful, but a rough mapping is:

- First generation – machine language

- Second generation – assembly language

- Third generation – high-level compiled languages

- Fourth generation – database and scripting languages

- Fifth generation – integrated development environments / declarative problem-solving systems

Newer languages generally extend capabilities rather than outright replace older ones. C and Fortran remain in widespread use in areas that rely on decades of libraries and proven implementations.

[NOTE: I had originally intended to write a second Insights article covering some obscure topics not covered here, but I’m not going to get around to it, so I should stop pretending otherwise.]

Studied EE and Comp Sci a LONG time ago, now interested in cosmology and QM to keep the old gray matter in motion.

Woodworking is my main hobby.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!