Ultra-Wide-Angle Lenses: Design, Use, and Guide

Note, unless otherwise specified, all focal lengths are in terms of the 35mm image format.

Table of Contents

Overview: why ultra-wide-angle lenses matter

Recently there has been a flurry of new high-performance ultra-wide-angle lenses introduced to the consumer market. Their imaging properties differ substantially from other photographic lenses, and the techniques used with them are also different. Because these lenses have only recently become widely available, many photographers have not yet had a chance to use them, so this update on ultra-wide lenses may be useful.

Availability and further reading

There are many online guides explaining how to compose with an ultra-wide. For example: https://digital-photography-school.com/how-to-get-the-best-results-from-ultra-wide-lenses/

Field of view and focal length

Relation to human vision

Ultra-wide lenses have fields of view significantly wider than your natural vision. Natural human vision for each eye is about 55 degrees, roughly equivalent to a 45mm focal length lens. Until fairly recently (around 2005), high-performance camera lenses with focal lengths shorter than 18mm were difficult to find. Today, interchangeable-camera users can buy many rectilinear lenses with fields of view exceeding 110 degrees.

Ultra-wide vs fisheye

The distinction between wide-angle and ultra-wide is fuzzy, but a good rule of thumb is: if the lens focal length is shorter than the short side of the sensor (24mm for full-frame 35mm format), the lens is called “ultra-wide.” “Fisheye” lenses have fields of view up to and exceeding a full hemisphere. The primary distinction is that an ultra-wide lens is designed to minimize distortion (rectilinear), while fisheye lenses intentionally incorporate strong distortion. With rectilinear ultra-wides, straight lines ideally remain straight.

How focal length affects what you see

Common focal lengths and examples

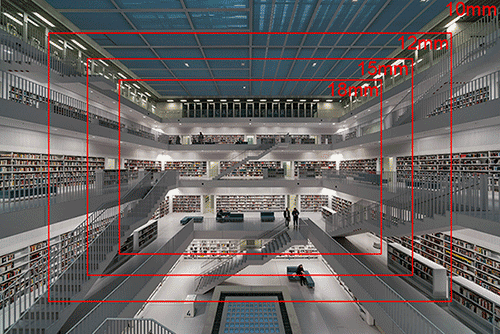

The shortest rectilinear focal length commonly available (as of 2017) is a 10mm “hyper-wide” lens with a field of view near 130 degrees. Several companies provide 11mm lenses; others offer 12mm, and 14mm/15mm lenses are now commonplace. There are even ultra-wide zooms and an ultra-wide tilt-shift lens. To give a sense of how the field of view varies with focal length, see this image:

For reference, a 50mm lens would typically see only the central group of two bookshelves and the staircase in the example above.

History and notable designs

Early milestones

Wide-angle lens design began in 1862 and, in my opinion, reached a zenith with designs such as the Hypergon and Metrogon/Topogon. These classic lenses were designed for large-format film; see:

https://www.cameraquest.com/hyper.htm

http://camera-wiki.org/wiki/Metrogon

Design challenges for ultra-wide lenses

Mount and flange considerations

Ultra-wide lenses have several design challenges unique to short focal lengths, including falloff (vignetting), flare, fabrication difficulties, filter compatibility, and chromatic aberrations. Many design constraints are driven by the relatively large distance between the lens mount flange and the sensor on SLR/DSLR cameras. On most SLRs this flange-to-sensor distance is longer than the lens’s back focal length, so designers use a retro-focus design — essentially the opposite of a telephoto design. Lenses placed closer to the image plane (as with rangefinder or mirrorless mounts) are generally easier to design and fabricate.

Because of this, ultra-wide lenses were developed for rangefinder cameras (and later became common on mirrorless bodies) well before SLRs. To the best of my knowledge, the only viable SLR ultra-wide lenses for many years were Nikon’s 15mm and 13mm lenses introduced in the late 1970s and early 1980s and later discontinued.

Although some development of APS-C-format ultra-wides occurred in the early 2000s, modern high-performance full-frame 35mm ultra-wides did not become common until around 2010, when Nikon, Canon, and Zeiss introduced new fixed and zoom ultra-wides. More recently, additional companies have released high-performance full-frame ultra-wides down to 10mm (for example, Voigtländer’s 10mm hyper-wide). Several technical reasons explain why ultra-wide lens design lagged behind telephoto development.

Front-element size and curvature

One major difficulty is the size and shape of the front element. Shorter focal lengths usually require more strongly curved front elements (similar to fisheye designs). For example, Sigma’s 14mm f/1.8 lens has an 80mm aspherical front element, while the Nikkor 13mm f/5.6 front element measures about 110mm across. These large, strongly curved elements are both difficult to manufacture and impressive to see.

Flare susceptibility and chromatic correction

Strongly curved front elements increase susceptibility to flare and glare. Lenses designed for mirrorless or rangefinder mounts have smaller diameters because the lens sits closer to the sensor, which helps reduce flare.

A second difficulty is correcting transverse chromatic aberration produced by dispersion in large, curved glass elements. Many of the modern lens designs became possible thanks to new optical glass types (extra-low-dispersion and anomalous partial-dispersion glasses) introduced by major glass foundries.

Falloff (vignetting)

Falloff—the optical throughput as a function of image height—occurs because the entrance pupil (the projection of the aperture stop into object space) appears to change shape and effective area for off-axis rays. At more oblique angles the round aperture appears elliptical to the incoming rays, reducing throughput. Correcting falloff becomes harder as the field of view increases. Non-optical mitigations historically included a “star fan” supplied with some Hypergon lenses and center (stoppage) filters.

Practical issues: sensors, filters, and use

Sensor and Bayer filter concerns

Digital sensors introduce a specific issue: the Bayer filter array assumes light arrives within a moderate cone of angles. Ultra-wide lenses generate rays that hit the sensor at more extreme angles near the periphery, and the Bayer filter stack may not respond the same way to those oblique rays. The result can be chromatic or color-shift effects around the image periphery that are independent of optical transverse chromatic aberration.

Filters and handling

The large front elements on many ultra-wides also make filter use difficult. Aside from the sheer size of the required filters, some lenses simply lack a filter thread. Third-party makers have produced large square filter solutions, and some older Nikkor designs include a rear filter slot. Using polarizers with wide fields of view can create dramatic effects across the sky (whether desirable depends on intent). Rangefinder/mirrorless ultra-wides with smaller diameters generally offer more practical filter options.

Other mounts

What is new for SLR users is also appearing across other mounts. For C-mount cameras, for example, there are now 13mm focal-length lenses with around a 135-degree field of view — roughly equivalent to the 10mm hyper-wide on full-frame.

How low can designers go?

Limits and scale

It’s unclear how much further rectilinear ultra-wides can be pushed because the required front-element size scales rapidly with decreasing focal length. Looking at the large front elements on extreme fisheyes—like the Nikkor 6mm f/2.8 and the Coastal Optics (Jenoptik) 7.45mm f/2.8—gives a sense of scale. Note those are fisheyes, so their front elements are smaller than what a rectilinear lens of equal focal length would require.

For comparison, the large-format 60mm Hypergon had a 135-degree field of view; scaling that down to 35mm format gives an equivalent near 7mm. The 10mm hyper-wide approaches that field of view while offering better throughput and practical handling.

Conclusion

Final thoughts

In summary, the recent explosion of high-performance ultra-wide lenses gives photographers many new choices at the very short end of the focal-length range. Advances in glass, manufacturing, and optical design have made rectilinear ultra-wides practical for more cameras and use cases than ever before, but those lenses still come with unique design trade-offs and practical considerations to learn and manage.

PhD Physics – Associate Professor

Department of Physics, Cleveland State University

Funny thing. I was very chuffed with how well my Pentax 14mm lens performed but, on the other hand, I was disappointed that the pictures don't 'look' wide angle. It's almost as if I need to give them a digital nudge to get that wide angle effect. It's just the same as people who claim to like vinyl records. I guess.

BTW, good article, @Andy Resnick.

Given that lens distortion can now be removed digitally, I wonder if it is better to do that then to use extra glass to make likes straight optically?

I take it this article is only about cameras with 35 mm size sensors? Lenses with 180° already exist on devices that pair two of them to image 360° video.

http://www.bestbuy.com/site/ricoh-t…ffcode=pg174715&ksdevice=c&lsft=ref:212,loc:2I didn't mean to implicitly discuss only 35mm-sized sensors; there are ultra-wide lenses for medium and large format sizes as well (the Super Angulon and Grandagon series of lenses, for example).

The Theta S and similar cameras (KeyMission 360, for example) use multiple sensors, and I also distinguished between fisheye lenses that have large distortion from rectilinear lenses, which do not. I focused on the development of new rectilinear ultrawide lenses.

The shortest focal length currently available (2017) is a 10mm “hyperwide” lens sporting a field of view of 130 degrees.

Reference https://www.physicsforums.com/insights/new-high-performance-ultra-wide-angle-lenses/I take it this article is only about cameras with 35 mm size sensors? Lenses with 180° already exist on devices that pair two of them to image 360° video.

http://www.bestbuy.com/site/ricoh-t…ffcode=pg174715&ksdevice=c&lsft=ref:212,loc:2

Andy, curious if you have ideas on where lens technology goes from here?Good question- although predicting the future is a fool's errand :) In general the trend is to larger apertures, reduced size/weight, decreased chromatic aberrations, and improved accutance. All of this is contingent on developments in optical materials- mainly glass- and the ability to grind aspheres. Incorporation of image stabilization is increasing as well. These developments all fall under "improved performance of existing lens designs".

Something more 'exotic' I'm interested in is 3-D PSF engineering. That is, rather than simply design improved performance in the focal plane, the entire PSF can be designed- at least that's what is claimed for the new Nikkor 58/1.4. It's an interesting idea.

Andy Resnick submitted a new PF Insights postnice write-up, Andy, thanks :)

my goto UW angle lens is my Samyang 14mm, f2.8

View attachment 114964

I have been quite pleased with it's quality considering its affordable ~ AU$360 price tag

particularly on wide angle astrophotography where pinpoint light sources from stars gives a good test

Andy, curious if you have ideas on where lens technology goes from here?