Why Uranus Spins on Its Side: Tilt, Theories, Models

Table of Contents

Uranus’ Peculiar Tilt

Uranus spins on its side. It has an obliquity (tilt) of 98° — its rotation axis lies closer to the ecliptic plane than any other planet — and astronomers still debate how it got that peculiar tilt.

Uranus Key Points

- Uranus has an obliquity (tilt) of 98° — its rotation axis is closer to the ecliptic plane than any other planet.

- For many years the conventional explanation was one or more giant impacts early in Uranus’s history.

- Scientists now propose an alternative: a spin–orbit resonance driven by a massive circumplanetary disk.

- Spin–orbit resonance is a secular resonance in which the precession of Uranus’ spin axis resonates with the planet’s orbital precession.

- Computer models that include a circumplanetary disk (especially a model where Uranus grows while the disk dissipates) can tilt Uranus substantially, although additional events may be required to reach the current 98°.

Problems with the Giant-Impact Theory

Conventional wisdom has long held that one or more giant impacts knocked Uranus onto its side when the planet was very young. Researchers point out several problems with that scenario.

First, if Uranus suffered multiple giant impacts but Neptune did not, we would expect their rotation rates to differ significantly because impacts can speed up or slow down rotation. In fact, a day on Uranus and a day on Neptune differ by only about 6% (Uranus: 17.2 hours; Neptune: 16.2 hours).

Second, giant impacts would likely disrupt a planet’s satellite system. If Uranus had experienced such violent collisions, we might expect its moon system to have an anomalously low total mass. Instead, Uranus’ satellites have roughly the mass expected for a normal satellite system.

Third, it is extremely difficult to design a single impactor large enough to tilt Uranus to its present obliquity; invoking multiple impacts is possible but complicates the scenario. Fourth, giant impacts would heat Uranus enough to vaporize substantial interior volatiles, which should produce mostly icy satellites — yet Uranus’ moons are relatively rock-rich.

Circumplanetary disk hypothesis

Because of these issues, scientists have proposed an alternative: spin–orbit resonance caused by a massive circumplanetary disk. Researchers simulated a young Uranus and Neptune, each surrounded by a large disk of gas and dust, to test whether disk-driven resonances could produce large tilts.

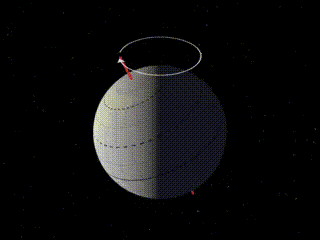

Explainer video

Watch a video explaining the mechanism.

What Is Spin–Orbit Resonance?

In general, resonance occurs when two periodic motions have commensurate frequencies — think of pushing a child on a swing at the right rhythm to make the swing go higher. An example of orbital resonance is Pluto and Neptune: Pluto completes two orbits for every three Neptune orbits, which stabilizes Pluto’s orbit.

Spin–orbit resonance is a type of secular resonance. In this case, the precession of Uranus’ spin axis resonates with changes in Uranus’ orbital orientation (orbital precession). Put simply, the spin-axis precession rate and the orbital precession rate become commensurate, allowing the spin axis to be driven to higher obliquity.

Orbital precession is typically much slower than the short orbital periods, so resonance is rare. For example, Earth’s axial precession period is about 26,000 years, while its orbital period is one year. For Uranus to enter spin–orbit resonance, its precession rate must be increased; a massive circumplanetary disk can provide the necessary torque to raise the precession rate during the planet’s early evolution.

Figure 1: Showing precession of the Earth’s spin axis (23.5°). Credit: Robert Simmon (NASA)

Growing a Tilted Ice Giant

Modeling the disk–planet interaction

As the ice giants formed, each likely possessed a circumplanetary disk. These disks are relatively short-lived — on the order of ~1 million years — before the material either falls into the planet or coalesces into moons. This means Uranus had roughly one million years for disk-driven processes to change its obliquity before the disk dissipated and the tilt became fixed.

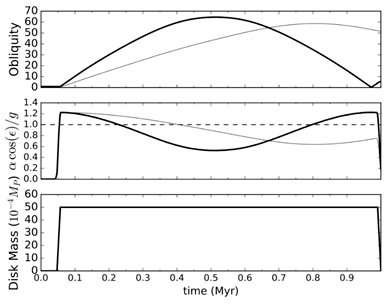

Figure 2: Model 1 (constant disk): changing obliquity over one million years.

Obliquity evolution is sensitive to the disk lifetime. The middle panels in the figures show how close the system comes to perfect resonance (dashed line).

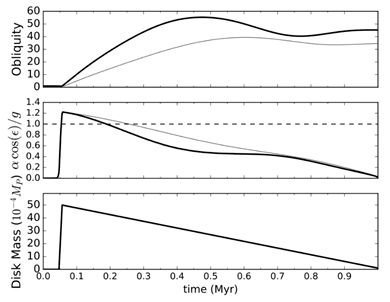

Figure 3: Results for a disk that slowly dissipates over one million years. Obliquity increases and then settles near ~45°.

Model 1

The simplest model uses a disk with constant mass for 1 million years, then the disk disappears instantly. In Figure 2 the obliquity (top panel) swings from 0° up to ~65° and then back toward 0°. A constant-mass disk can drive large excursions, but it can also reverse the tilt, making the outcome unpredictable.

Model 2

This model uses a more realistic disk that slowly dissipates over one million years (Figure 3, bottom panel). The obliquity reaches a maximum of ~55° and then settles near ~45°. A dissipating disk tends to hold a tilt better than a constant disk, but ~45° is still far short of the observed 98°.

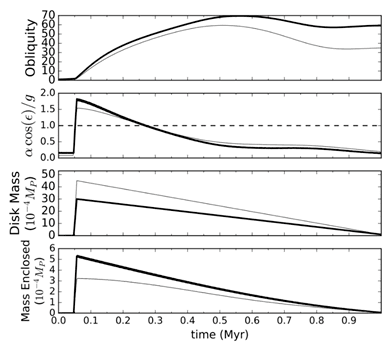

Figure 4: Model 3 results: a slowly dissipating disk while material accretes onto Uranus. After one million years the obliquity settles near ~60°.

Model 3

Model 3 is like Model 2 but allows Uranus to grow in mass as disk material falls onto the planet. The obliquity peaks near ~70° and then settles around 60° once the disk is gone. This model reproduces the largest tilts in the experiments and is considered the most realistic of the three because it captures both disk torques and planetary mass growth.

Conclusions

Researchers conclude that spin–orbit resonance driven by a massive circumplanetary disk can plausibly produce large tilts (up to ~70° in their best cases). Reaching the present-day 98° may still require at least one additional event — for example, a late large impact — but that single impact would be much easier to arrange than a sequence of several giant impacts.

The authors ran many additional models beyond the three summarized here. Although some reproduce observed features of the Uranus–Neptune system, reconstructing events from nearly five billion years ago with limited observational constraints remains challenging.

References

Gordon, M. (SETI Institute); Hamilton, D.; Rogoszinski, Z. (University of Maryland, College Park); Showalter, M. (SETI Institute); Simmon, R. (NASA).

A Nuclear Fusion Physicist and Astrophysicist.

BSc Physics & Engineering, MSc Nuclear Physics & Engineering, MSc Astrophysics, PhD Plasma Physics

”

The impactor theory could always be ruled out for the simple reason that Uranus is not a solid body!

”

”

Who said anything about violating the conservation of angular momentum?! Since the mantle is not solid, the collision is inelastic – much of the kinetic energy goes into heating the material(which would also be true even if the mantle was made of solid ice) resulting in turbulence, which then subsides as it’s energy gets radiated away due to friction.

”

Even a collision with a dense fluid would still transfer a substantial amount of angular momentum to the planet. Besides, the heating of the material of both bodies in any collision of this magnitude turns large parts of them molten anyways, so you’re still dealing with a fluid-on-fluid interaction to some degree.

Think of it this way. All of that material that gets pushed away in a certain direction by the collision would:

1. Press directly on the rest of the planetary material, transferring momentum directly; or

2. ‘Slide’ along, interacting through friction with the surrounding material, transferring momentum that way; or

3. Get ejected some distance, eventually falling back, where its impact would transfer momentum; or

4. Get ejected completely, transferring little to no momentum to the planet in the process.

”

Saying “God did it” is “religious speak” but saying “Evolution did it” isn’t. Go figure.

”

Did someone say that?

Recent relevant news

Scientists found a secret in old Voyager 2 data. This is why we need to revisit Uranus and Neptune

[URL]https://www.cnn.com/2020/03/27/world/uranus-plasmoid-voyager-2-scn/index.html[/URL]

Such an interesting topic and the article / work is well thought out. The argument against a collision is very convincing and, as [USER=511972]@TeethWhitener[/USER] says, puts a long lasting nagging worry to bed (for me at least). It could be applied to all sorts of tilt situations.