Animal Speed Scaling: Body-Lengths per Second Across Sizes

Table of Contents

Introduction

In a recent American Journal of Physics issue, I read an interesting paper by Nicole Meyer-Vernet and Jean-Pierre Rospars examining the top speeds of organisms across a huge range of sizes, from bacteria to blue whales. They found that the time it takes an animal to traverse its own body length is, to zeroth order, almost independent of mass across roughly 21 orders of magnitude. The authors derive a simple scaling argument and an order-of-magnitude estimate that explains this remarkable observation.

Before summarizing their argument, I give a brief overview of scaling arguments and why they are a powerful tool for extracting broad behavior from complex systems.

Scaling Arguments

There is a common false dichotomy in physics: either you give a quasi-philosophical, descriptive explanation, or you present rigorous formulae that require long study. Between these extremes sits a very useful middle ground: scaling arguments.

A scaling argument is a step above a Fermi calculation. In a Fermi calculation we estimate values of parameters and multiply them to get an order-of-magnitude result, typically ignoring constants of order unity. With a scaling argument we ask how a dependent quantity changes as an independent quantity is varied, we neglect dimensionless coefficients, and we focus on limiting behavior and power laws.

Square–Cube Law

A classic example is the Square–Cube Law, known since Galileo and highlighted in Haldane’s essay On Being the Right Size. If an object is scaled by a factor of two in every linear dimension, its volume and mass increase by 2^3 = 8, while its cross-sectional area increases only by 2^2 = 4. Thus as organisms (or structures) get larger, mass grows faster than the area available to support it, so weight becomes more significant relative to strength.

Another illustrative case is terminal velocity: drag scales with cross-sectional area (∝ radius^2, or roughly mass^(2/3) for similar shapes), while weight scales with volume (∝ radius^3, or mass^1). Haldane describes the practical consequence:

You can drop a mouse down a thousand-yard mine shaft; and, on arriving at the bottom, it gets a slight shock and walks away, provided that the ground is fairly soft. A rat is killed, a man is broken, a horse splashes.

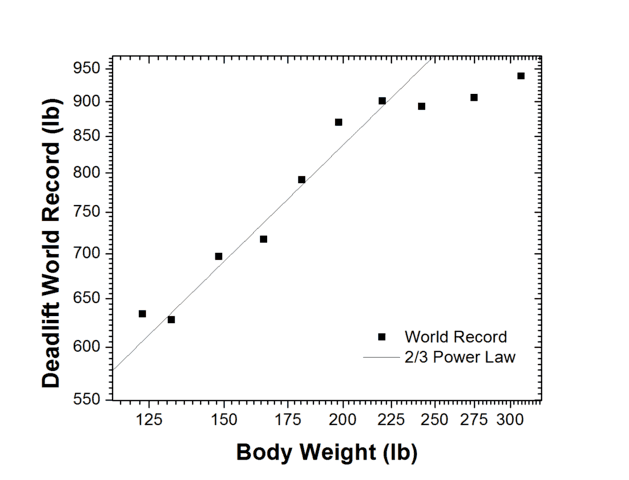

Example: Deadlift Records and the 2/3 Power Law

To test a simple scaling prediction, I assumed that a human’s cross-sectional area scales as the square of height (or roughly as mass^(2/3)). If peak strength scales with cross-sectional area, then peak strength should scale as mass^(2/3).

I looked up the deadlift world-records for men across weight classes. The records follow the 2/3 scaling law reasonably well from the smallest lifters up to about 220 lb. Above that weight the scaling breaks down because competitors tend to have more fat without a proportional increase in muscle. A power-law fit yields a best-fit exponent of 0.67 ± 0.05, consistent with the 2/3 prediction. (I use this example to show how a simple scaling argument can provide a useful prediction for a complex biological system.)

The Animal Speed Paper: Main Observation

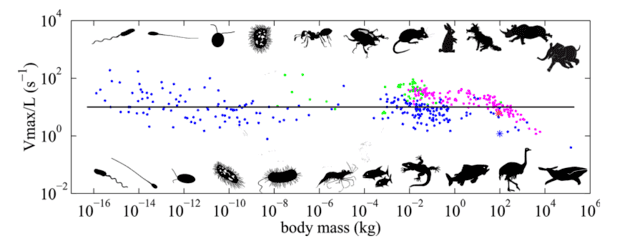

The central observation of Meyer-Vernet and Rospars is summarized in a single figure: they plot how many body-lengths an animal can cover per second as a function of mass. For example, Usain Bolt can cover roughly six of his own heights per second, while elite swimmer Florent Manaudou covers about one body length per second in the pool.

Their dataset spans organisms from bacteria (≈ 10-16 kg), which swim with rotating flagella, up to whales (≈ 105 kg) that undulate their bodies — covering about 21 orders of magnitude in mass. The authors find that the traversal frequency (body-lengths per second) is roughly independent of mass across most of this range. There is scatter, and some systematic deviation at the largest sizes, but the best-fit slope is around −0.06, close to zero, so the zeroth-order conclusion stands: traversal frequency is nearly mass-independent.

Why a Mass-Independent Frequency Emerges

The authors aim to explain why body-lengths-per-second is roughly constant and to estimate its magnitude to within about an order of magnitude.

They identify three broadly shared features of motile organisms:

- Density: Most life is water-like and roughly buoyant, with density ≈ 1 kg/L.

- Muscle stress: Muscle force per unit area, determined by protein interactions, is similar across taxa. The paper cites a characteristic muscle stress of roughly 20,000 N/m2.

- Metabolic power per unit mass: Related to heat-transfer and physiology. The paper adopts a value on the order of 2 W per kilogram of muscle (the article cites controversy in the literature about the precise value; the derivation uses an order-of-magnitude estimate).

Using dimensional analysis, they combine these quantities to obtain the units of frequency (1/s), yielding an estimate for the maximum traversal frequency. The result is, to order of magnitude:

Maximum speed / body length ≈ (metabolic power per mass × density) / (muscle stress) ≈ 10 body lengths per second

This expression is essentially independent of body mass (zeroth power of mass), which is consistent with the data. The claim is not that every organism attains 10 body-lengths/s, but that most organisms fall within a factor of ten around this estimate (i.e., roughly between 1 and 100 body-lengths/s in the extremes of their model). The paper also offers mechanical reasoning about how the energy required to move appendages (flagella, legs, tails) leads to similar characteristic frequencies. They note a weak negative scaling for the largest organisms and argue that the mass-independent scaling applies up to body sizes of about 1.4 m.

Conclusion

I enjoyed this paper because it takes a striking empirical pattern and explains it with simple, broadly applicable physical ideas: scaling analysis, dimensional reasoning, and order-of-magnitude estimates. It is striking that three shared physiological features lead to a nearly universal locomotion frequency across so many orders of magnitude in mass.

Click here for the forum comments.

Ph.D. McGill University, 2015

My research is at the interface of biological physics and soft condensed matter. I am interested in using tools provided from biology to answer questions about the physics of soft materials. In the past I have investigated how DNA partitions itself into small spaces and how knots in DNA molecules move and untie. Moving forward, I will be investigating the physics of non-covalent chemical bonds using “DNA chainmail” and exploring non-equilibrium thermodynamics and fluid mechanics using protein gels.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!