John Baez Interview — Mathematical Physicist & Networks

We are proud to introduce you to Mathematical Physicist and PF member John Baez!

Table of Contents

Give us some background on yourself

I’m interested in all kinds of mathematics and physics, so I call myself a mathematical physicist. I’m a math professor at the University of California, Riverside (UC Riverside), where I’ve taught since 1989. My wife, Lisa Raphals, joined the faculty nine years later; among other things she studies classical Chinese and Greek philosophy.

I earned my bachelor’s degree in mathematics at Princeton. For my undergrad thesis I studied whether a computer can solve Schrödinger’s equation to arbitrary accuracy. In the end it became clear that you can. I was very interested in mathematical logic and used the theory of computable functions in my thesis, but I decided it wasn’t very helpful for physics. After reading the poetic last chapter of Misner, Thorne and Wheeler’s Gravitation, I decided quantum gravity was the problem to work on.

Graduate school and early research

I went to math grad school at MIT but didn’t find anyone to work with on quantum gravity, so I did my thesis on quantum field theory with Irving Segal. He was one of the founders of constructive quantum field theory, which aims to rigorously prove that quantum field theories make mathematical sense and obey expected axioms. It was a difficult subject; I didn’t accomplish everything I hoped, but I learned a great deal.

After a postdoc at Yale I switched to classical field theory, mainly because it was something I could make progress on. On the side I continued trying to understand quantum gravity. String theory was rising in prominence, and it would have been easier to jump on that bandwagon, but much early work studied strings on a fixed background spacetime. Quantum gravity should describe a variable, quantum-mechanical geometry of spacetime, so I wasn’t comfortable with background-dependent approaches.

Loop quantum gravity, spin networks and n-categories

I obtained a professorship at UC Riverside based on my classical field theory work. At a conference in Seattle I heard Abhay Ashtekar, Chris Isham and Renate Loll give talks on loop quantum gravity. Their background-free and mathematically rigorous approach appealed to me, so I began working on loop quantum gravity.

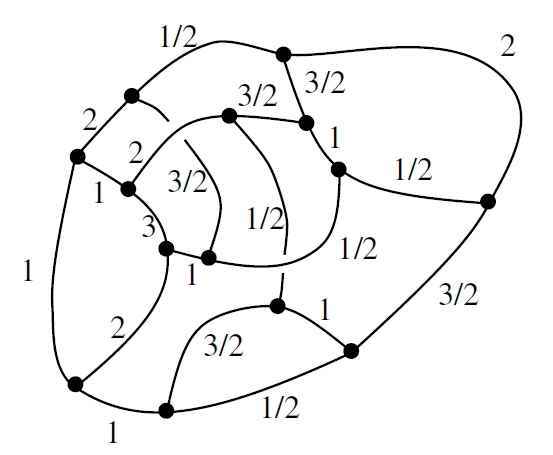

Quantum gravity is often easier in lower dimensions. I became interested in how category theory can be used to formulate quantum gravity in three spacetime dimensions. This led to a radical conception of space where geometry is described in a thoroughly quantum-mechanical way. Ultimately, space can be a quantum superposition of “spin networks”, which resemble Feynman diagrams. Roughly speaking, a spin network represents a virtual process in which particles move and interact; if we know the likelihood of each process, we can infer the geometry of space.

Loop quantum gravity seeks to do the same for four-dimensional quantum gravity, but it has been more challenging. Louis Crane proposed that 4-dimensional quantum gravity may require a more sophisticated structure: a “2-category”. I had not heard of 2-categories before. Category theory studies objects and processes that turn one object into another; in a 2-category there are also “meta-processes” that turn one process into another.

I became excited about 2-categories. Later James Dolan introduced me to n-categories, which opened many possibilities. He came to UC Riverside to work with me, and we began thinking about n-categories alongside loop quantum gravity.

Dolan was technically my graduate student, but I learned a lot from him. In 1996 we wrote “Higher-dimensional algebra and topological quantum field theory”, which I consider one of my best papers. It contains bold hypotheses about n-categories and their links to mathematics and physics. At the time, good definitions of n-categories existed only for n < 4, so we framed our ideas as hypotheses rather than precise conjectures. Since then many researchers have accepted and proved parts of these hypotheses. Jacob Lurie advanced one statement and provided a 111-page outline of a proof, though some foundational definitions still needed refinement.

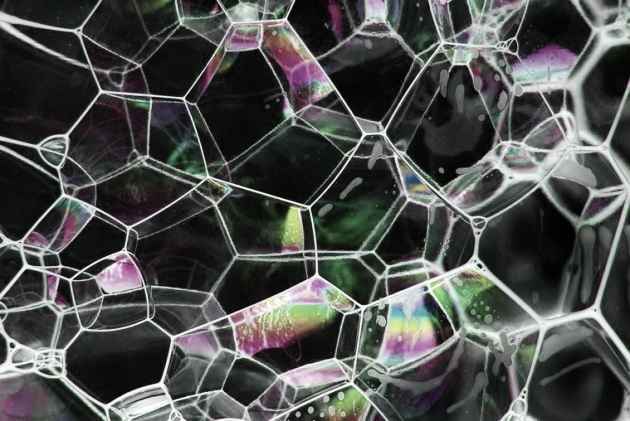

In 1997 I introduced “spin foams”, structures like spin networks but with an extra dimension. Spin networks have vertices and edges; spin foams also have 2-dimensional faces — imagine a soap-bubble foam. The idea was to use spin foams to give a purely quantum description of spacetime geometry. Mathematically, this corresponds to moving from a category to a 2-category.

Multiple spin foam theories have been proposed, but it’s unclear whether any fully succeed. In 2002 Dan Christensen, Greg Egan and I performed large-scale numerical calculations and found that the most popular spin foam model at the time produced results very different from expectations; I believe our work essentially undermined that model.

Shifts in focus: from quantum gravity to n-categories and beyond

I found that spending years testing spin foam models was unattractive to me, and I didn’t enjoy programming. Meanwhile, n-category theory was mathematically natural for me and a source of many new ideas. So I shifted my focus from quantum gravity to n-categories.

Quitting quantum gravity was emotionally difficult. It felt like leaving a “holy grail” pursuit, and many colleagues considered unifying quantum mechanics and general relativity the most important problem in physics. It took years to shift my mindset.

Ironically, leaving quantum gravity allowed me to explore string theory more freely. As a branch of mathematics it’s beautiful, and n-categories apply here as well: particles relate to categories while strings relate to 2-categories. I explored this with Urs Schreiber and John Huerta.

Around 2010 I began focusing on environmental issues and math relevant to engineering and biology for the planet’s sake. That required another painful transition. Fortunately, researchers like Urs Schreiber and others continue work on n-categories and string theory, often advancing further than I might. I follow these developments from the sidelines.

It’s likely we’ll need many more ideas before we make major progress on quantum gravity, but I remain confident that n-categories will play a role. I’m glad to have helped advance that field.

Your uncle, Albert Baez — early influence

My uncle had a huge effect on me. He’s better known as the father of folk singer Joan Baez, but he began in optics and helped invent the first X-ray microscope. Later he focused on physics education, particularly in countries then referred to as “third-world countries.” For example, in 1951 he helped establish a physics department at the University of Baghdad.

When I was a kid he worked for UNESCO and would visit Washington D.C., staying with my parents. He would open his suitcase and pull out amazing gadgets — diffraction gratings, holograms — and explain how they worked. I decided physics was the coolest thing there is.

At age eight he gave me his book The New College Physics: A Spiral Approach, which I tried to read immediately. The “spiral approach” is pedagogically valuable: instead of covering a topic once, you revisit it repeatedly, increasing depth each time. He taught me not only physics but also how to learn and teach.

When I was fifteen I spent a couple of weeks at his Berkeley apartment. He showed me the Lawrence Hall of Science, where I got my first taste of programming — in BASIC, with programs stored on paper tape in 1976. He also gave me The Feynman Lectures on Physics. The following summer, while working at a state park building trails, I tried to learn quantum mechanics from the third volume of the lectures. The other kids probably thought I was a complete geek — which I was.

Give us some insight on what your average work day is like

During the school year I teach two or three days a week. On teaching days I prepare classes starting at breakfast. Teaching is lots of fun; right now I’m teaching an undergraduate course on game theory and a graduate course on category theory, and I run a category theory seminar. I also meet with my graduate students for a weekly four-hour session to review progress and push research forward.

On non-teaching days I spend much of my time writing. I love blogging, but I try to devote significant time to writing papers. Early drafts are often tough, but near the end a paper “practically writes itself” and I find it hard to stop adding improvements. Those are very satisfying days.

In summer I don’t teach, so I often get a lot of writing done. I spent two years at the Centre of Quantum Technologies in Singapore, and since 2012 I’ve worked there during summers. Sometimes I bring grad students; mostly I focus on writing.

I also spend plenty of time with my wife — talking, cooking, shopping, working out — and we like to watch TV in the evenings, mainly mysteries and science fiction. We do a lot of gardening. When younger that seemed boring, but as subjective time speeds up with age you notice plants growing: planting seedlings, watching them grow into an orange tree, and eating the fruit for breakfast is tremendously satisfying.

I enjoy playing piano and recording electronic music, but doing these well requires long blocks of time I don’t always have. Music is pure delight; when not listening I’m often composing mentally.

If I gave in to my darkest urges and became a decadent wastrel I might spend all day blogging, listening to music, recording music and working on pure math. But I need other activities to stay sane.

What research are you working on at the moment?

I’ve been trying to finish a paper called “Struggles with the Continuum”, about the problems physics has with infinities arising from treating spacetime as a continuum. Writing sections that summarize quantum field theory is challenging because the subject is complicated and sprawling. To stay motivated I broke the paper into blog articles and posted them on Physics Forums.

For fun, I’ve been collaborating with Greg Egan on projects involving the octonions. The octonions are a number system where you can add, subtract, multiply and divide; such division algebras exist only in dimensions 1, 2, 4 and 8: the real numbers (1D), the complex numbers (2D), the quaternions (4D) and the octonions (8D). The octonions are the largest and the strangest: multiplication of octonions is not associative, so ##(xy)z## need not equal ##x(yz)##. Despite sounding crazy at first, octonions connect to string theory and other areas.

There is a notion of “integers” for the octonions; integral octonions form a lattice in 8 dimensions called the E8 lattice. Another important lattice lives in 24 dimensions, the Leech lattice. Both connect to string theory: 8+2 = 10 (superstring dimension) and 24+2 = 26 (bosonic string dimension); the +2 comes from the 2-dimensional worldsheet of the string.

Because 3×8 = 24, Greg Egan and I explored building the Leech lattice from three E8 copies. There was a known trick; it took time to understand, and then Egan showed the trick can be done in exactly 17,280 ways. I plan to write up the proof; there’s beautiful geometry involved.

My main current work uses category theory to study networks. I’m interested in many network types — electrical circuits, neural networks, chemical reaction networks and more. Different fields focus on different networks, but there is insufficient cross-disciplinary communication, so mathematicians can help build a unified theory of networks.

I have seven graduate students on this project — eight if you include Brendan Fong, whose dissertation I’ve helped advise even though he’s an Oxford student.

Brendan was the first to join. I initially wanted him to study electrical circuits as a familiar starting point, but he developed a general category-theoretic framework for networks. We applied it to electrical circuits and other systems.

Blake Pollard, a student in our physics department, collaborated with Brendan and me to develop a category-theoretic approach to Markov processes, reducing them to electrical circuits. Blake is now extending these ideas to chemical reaction networks.

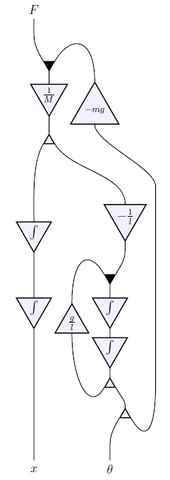

My math-department students work on related topics. Jason Erbele studies control theory and how “signal flow diagrams” used in engineering can be understood categorically; he has developed categorical descriptions of signal flow. Jason uses a different framework called PROPs, which are longstanding tools in algebraic topology. Franciscus Rebro has developed PROPs further for our project.

Brandon Coya has worked on electrical circuits, extending Brendan’s work and unifying Brendan’s formalism with PROPs. Adam Yassine is beginning to study networks in classical mechanics: instead of analyzing a single system via a Hamiltonian, he is setting up frameworks to connect many systems into networks.

Kenny Courser and Daniel Cicala are exploring bringing 2-categories into network theory. Categories describe systems and processes that turn inputs into outputs; 2-categories describe meta-processes that turn one process into another. For example, a 2-category can formalize a “simplification” that replaces two resistors in series with a single resistor.

Ultimately I want to apply these ideas to biochemistry. Biology can seem messy to physicists and mathematicians, but I suspect a beautiful logic underlies it. Biological systems are full of networks that change over time, so 2-categories may provide a natural language for them. Convincing others won’t be easy — but that’s okay.

Continue to Part 2 of this interview

I’m a mathematical physicist. I work at the math department at U. C. Riverside in California, and also at the Centre for Quantum Technologies in Singapore. I used to do quantum gravity and n-categories, but now I mainly work on network theory and the Azimuth Project, which is a way for scientists, engineers and mathematicians to do something about the global ecological crisis.

Please ! Tell me your opinion about it.Hypercomplex_numbers_and_their_applicationhttps://drive.google.com/open?id=0B6SDyydw3n_oZnNhZG00WkJlNXc

I hope I’m not beating a dead cow here, but….

”

The octonions are a number system where you can add, subtract, multiply and divide. Such number systems only exist in 1, 2, 4, and 8 dimensions”

and

“…that this is somehow because of the fact that [URL=’https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hairy_ball_theorem’]”every cow must have at least one cowlick”[/URL]…”

and

“Here’s the relation. … A sphere in n-dimensional space can have (n-1) linearly independent continuous vector fields if n = 1, 2, 4, or 8.

”

The “relation” is as John pointed out in the WP reference, yet the “cause and effect” seem to be reversed in Shyan’s comment. That is: the 1,2,4 and 8 limit on the dimensionality of numbers systems where you can add, subtract, multiply and divide is not “because of” the number of linearly independent continuous vector fields (or their number of hairy ball cowlicks).

It is the octonion limit on the number of dimensions (n=8) for normed division algebras (due to sedenions having zero divisors and the Cayley-Dickson construction) that constrains n<9. The number of linearly independent continuous vector fields within the modulo 8 periodicity of Clifford Algebras are related yet dependent rather than being a cause of any lack of "normed division" capability.

“Hmm, biochemistry. How about neurobiology? There seem to be networks there too.”

My concept of biology is so broad that it includes biochemistry, neurobiology, ecology and more. The network formalisms I’m developing are so general that they should have some relevance to all of these topics… though of course it’d take expertise to develop any one particular application to the point of doing something useful!

“I remember reading somewhere that this is somehow because of the fact that [URL=’https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hairy_ball_theorem’]”every cow must have at least one cowlick”[/URL], but there wasn’t much explanation! Can anybody give a clue?”

Here’s the relation. A sphere in n-dimensional space can have least one continuous nowhere vanishing vector field if and only if n = 2,4,6,8,… A sphere in n-dimensional space can have (n-1) linearly independent continuous vector fields if n = 1, 2, 4, or 8.

People know, for a sphere of any dimension, the maximum number of linearly independent continuous vector fields on it. See:

[LIST]

[*][URL=’https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vector_fields_on_spheres’]Vector fields on spheres[/URL], Wikipedia.

[/LIST]

These results subsume everything I just said, and more.

“Also, interesting interview, thanks!”

You’re welcome!

“I remember reading somewhere that this is somehow because of the fact that [URL=’https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hairy_ball_theorem’]”every cow must have at least one cowlick”[/URL], but there wasn’t much explanation! Can anybody give a clue?

Also, interesting interview, thanks!”

It has nothing to do with it. The “cow” theorem is about poles in odd dimensional spaces.

“Such number systems only exist in 1, 2, 4, and 8 dimensions”

I remember reading somewhere that this is somehow because of the fact that [URL=’https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hairy_ball_theorem’]”every cow must have at least one cowlick”[/URL], but there wasn’t much explanation! Can anybody give a clue?

Also, interesting interview, thanks!

By the way, thanks for explaining how many vertices overlap in this 2d projection of the E8 root polytope!

I stand corrected – it seems Tom does (at least for some images) change the default file upload CC Share-Alike Commons to “Public Domain”.

In checking though, he does have others that have the default (as, AFAIK, mine do) which does require attribution. So I guess, we need to double check each image.

Don’t get me wrong, I am ok w/putting my stuff in public domain w/o attribution requirements. In using the defaults I assumed proper etiquette was to cite WP sources as a matter of course.

e.g. [URL]https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Flower_of_life_triangular_11547-arccircle.svg[/URL]

[SIZE=5]

Licensing[/SIZE]

I, the copyright holder of this work, hereby publish it under the following license:

[IMG]https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/7/79/CC_some_rights_reserved.svg/90px-CC_some_rights_reserved.svg.png[/IMG]

[IMG]https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/1/11/Cc-by_new_white.svg/24px-Cc-by_new_white.svg.png[/IMG] [IMG]https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/df/Cc-sa_white.svg/24px-Cc-sa_white.svg.png[/IMG] This file is licensed under the [URL=’https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/en:Creative_Commons’]Creative Commons[/URL] [URL=’https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/deed.en’]Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International[/URL] license.

You are free:

[LIST]

[*]to share – to copy, distribute and transmit the work

[*]to remix – to adapt the work

[/LIST]

Under the following conditions:

[LIST]

[*]attribution – You must attribute the work in the manner specified by the author or licensor (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work).

[*]share alike – If you alter, transform, or build upon this work, you may distribute the resulting work only under the same or similar license to this one.

[/LIST]

” oh, and a minor point… it is my understanding that citation (author name and link if online) is still required to WP WikiMedia commons content. ”

I believe someone puts something in the public domain, that means anyone can do anything they want with it. If you read [URL=’https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:4_21_t0_E6.svg’]the page on which this image appears on Wikicommons[/URL] you’ll see it says:

“I, the copyright holder of this work, release this work into the [URL=’https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/en:public_domain’]public domain[/URL]. This applies worldwide.

In some countries this may not be legally possible; if so:

I grant anyone the right to use this work for any purpose, without any conditions, unless such conditions are required by law.

”

One reason I like Tom Ruen’s work so much is that he puts it into the public domain, thus freeing it up for worldwide use without any need for attribution. It’s a gift to the universe.

But of course, if Mr. X tries to put Mr. Y’s copyrighted work into the public domain, Mr. Y can argue with that.

”

oh, and a minor point… it is my understanding that citation (author name and link if online) is still required to WP WikiMedia commons content. ”

When someone puts something in the public domain, that means anyone can do anything they want with it. If you read [the page for this image on Wikicommons]([URL]https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:4_21_t0_E6.svg[/URL]) you’ll see it says:

“I, the copyright holder of this work, release this work into the [URL=’https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/en:public_domain’]public domain[/URL]. This applies worldwide.

In some countries this may not be legally possible; if so:

I grant anyone the right to use this work for any purpose, without any conditions, unless such conditions are required by law.

“

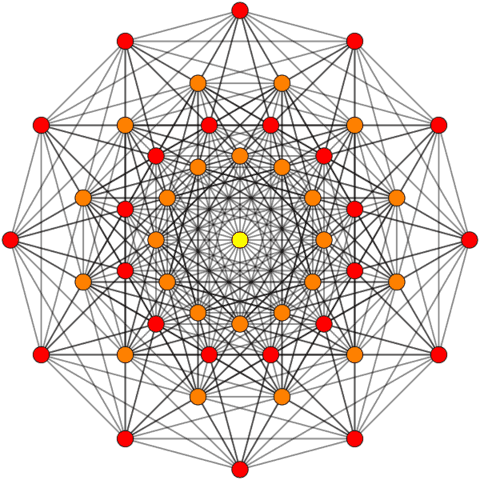

The 72 vertex and 720 edge E6 (as a subgroup of E8) in the E6 Coxeter plane (a Petrie projection) produces vertex overlaps of:

24 Yellow with 1 overlap

24 Orange each with 2 overlaps (48 vertices)

with none at the origin.

(which I have now included here:

[URL]http://theoryofeverything.org/theToE/2016/03/16/e8-in-e6-petrie-projection/[/URL])

See this work by Stembridge on this as well: [URL]http://www.math.lsa.umich.edu/~jrs/coxplane.html[/URL]

Taking all 240 of E8 vertices and 6720 edges produces a similar result but different (as you used in the article).

BTW – great article!

oh, and a minor point… it is my understanding that citation (author name and link if online) is still required to WP WikiMedia commons content. (of course, in this case the work was Tom Ruen’s – he simply took my basis vectors and produced the image using his own source code (rather than using the Mathematica tool I use and offer in the public domain).

“This article uses an E8 projection which I introduced to Wikipedia in Feb of 2010 here. ”

Cool! Maybe you mean E6 projection? I deliberately chose an image that was [URL=’https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:4_21_t0_E6.svg’]in the public domain[/URL] so I wouldn’t have to give attributions, but thanks for helping come up with it!

“Do you by any chance know Helmer Aslaksan? I would think so.”

No, I don’t know him. He[URL=’http://www.math.nus.edu.sg/aslaksen/’] seems like a cool guy[/URL], but I haven’t been hanging out in the math department at NUS.

“Thanks for giving me the chance to think about where I’ve been and where I’m going!

I’ll go back to the Centre for Quantum Technologies again at the end of June. My wife has been working at the Philosophy Department at NUS while I’ve been working there. We think this will be our last summer working in Singapore: we’ve had a good run of it, but we’re ready to try something new. Frankly I’d be happy to stay home and tend to our garden—I always get nervous about the plants when I’m gone during the hot summers in Riverside! But I suspect we’ll probably go to Europe next summer.”

Do you by any chance know Helmer Aslaksan? I would think so.

I think it's awesome that we have some prominent scientists and mathematicians here on PF.

Hmm, biochemistry. How about neurobiology? There seem to be networks there too.

I'm not sure, but I think Shyan's question was an attempt at humor (I laughed anyway). Yet, if he was asking a serious, the reason is that John was describing the conditions for "normed division algebras". The 1,2,4 and 8 dimensions are due to the 2^n nature of the Cayley-Dickson construction of the algebras.Add to this, given the reference to "division" algebra, ends at dimension 8 with octonions because the next level up (the 16 dimensional sedenions) contains "zero divisors" which prevents division in those cases. For my list of those zeros, see: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sedenion

This article uses an E8 projection which I introduced to Wikipedia in Feb of 2010 here. Technically, it is E8 projected to the E6 Coxeter plane.The projection uses X Y basis vectors of:X = {-Sqrt[3] + 1, 0, 1, 1, 0, 0, 0, 0};Y = {0, Sqrt[3] – 1, -1, 1, 0, 0, 0, 0};Resulting in vertex overlaps of:24 Red with 1 overlap24 Orange each with 8 overlaps (192 vertices)1 Yellow with 24 overlaps (24 vertices)This was subsequently recreated in the current article and 4_21 E8 WP page by Tom Ruen, source for the article.After doing this for a few example symmetries, Tom took my idea of projecting higher dimensional objects to the 2D (and 3D) symmetries of lower dimensional subgroups – and ran with it in 2D – producing a ton of visualizations across WP. :-)http://theoryofeverything.org/theToE/2016/03/16/e8-in-e6-petrie-projection/

Thanks for giving me the chance to think about where I've been and where I'm going!I'll go back to the Centre for Quantum Technologies again at the end of June. My wife has been working at the Philosophy Department at NUS while I've been working there. We think this will be our last summer working in Singapore: we've had a good run of it, but we're ready to try something new. Frankly I'd be happy to stay home and tend to our garden—I always get nervous about the plants when I'm gone during the hot summers in Riverside! But I suspect we'll probably go to Europe next summer.

Brilliant Insight into your life John! Are you planning to returning to the "Centre of Quantum Technologies" this year? Also I must imagine you have the most interesting dinner discussions with your wife. Philosophy and Physics :)