Quantum Mechanics and the Famous Double-slit Experiment

Table of Contents

Double-slit Key Points

- Quantum mechanics is known for its strangeness, including phenomena like wave–particle duality, which allows particles to behave like waves.

- The double-slit experiment is a central demonstration of that duality: even single particles, like photons, can produce wave-like interference.

- When an experiment measures which slit a particle goes through, it behaves like a particle. When that measurement is not made, an interference pattern appears, typical of waves.

- Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle connects the accuracy of a position measurement to uncertainty in momentum; this trade-off is central to the double-slit outcomes.

- De Broglie’s proposal of matter waves implies that all matter—not just light—exhibits wave-like properties.

- Wheeler’s delayed-choice experiment shows that deciding what to measure after a particle passes the slits can change which behavior (wave or particle) is observed.

- In principle, that temporal effect could reach back as far as the light’s transit time—potentially billions of years in extreme cases.

- The interpretation of these experiments varies; physicists differ on the philosophical implications.

Watch: Double-slit experiment video (YouTube)

Introduction

Quantum mechanics is famously strange. Schrödinger’s “dead-and-alive” cat, Einstein’s spooky action at a distance, and de Broglie’s matter waves are remarkable examples. Yet the greatest strangeness may be that quantum mechanics can be used to edit events that should already have happened—in other words, to re-write history.

Before we can understand how that is possible, we need to see how Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle accounts for wave–particle duality in the double-slit experiment.

The Double-Slit Experiment

The double-slit experiment is famous because it provides a clear demonstration that light behaves like a wave. But its importance goes further: as Richard Feynman said in 1966, “In reality, it contains the only mystery… In telling you how it works, we will have to tell you about the basic peculiarities of all quantum mechanics.”

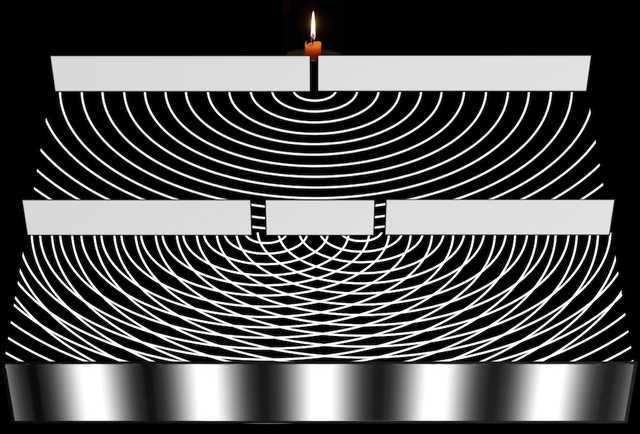

Figure 1: The double-slit experiment. Waves travel from the source (top) to the first barrier (one slit), then to the second barrier (two slits). Semi-circular waves from each slit interfere, producing peaks and troughs that form an interference pattern on a screen (bottom).

Based on work first described by Thomas Young in 1802, the apparatus consists of two vertical slits and a screen, as shown in Figure 1. Light from each slit interferes with light from the other slit to produce an interference pattern on the screen. This appears to prove that light consists of waves, even though the detected entities on the screen are individual particles—photons.

The bright regions in the interference pattern correspond to areas where photons land with high probability; the dark regions correspond to areas with low probability.

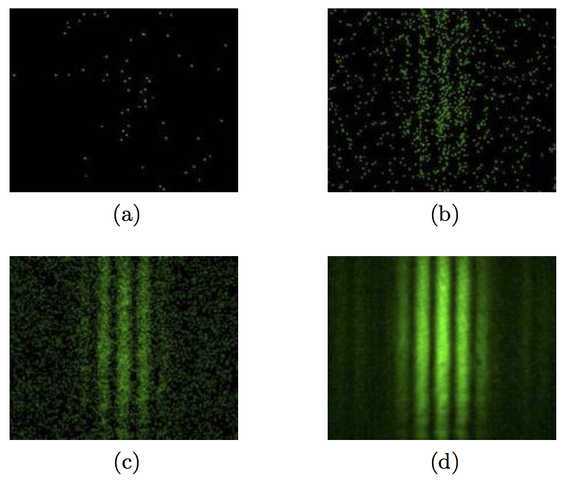

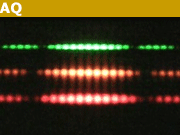

Figure 2: Emergence (a→d) of an interference pattern in a double-slit experiment, where each dot represents a photon. Reproduced with permission from Tanamura (Wikimedia).

Remarkably, the same interference pattern appears even when the light is so dim that only one photon at a time reaches the screen, as in Figure 2. With such a low photon rate, it can take weeks for the pattern to emerge. That a pattern emerges at all implies that a single photon behaves like a wave; heuristically, it seems as if the photon went through both slits at once. Only a wave can pass through both slits, yet only a photon can be detected at a single point on the screen. This apparent contradiction is central to the paradox.

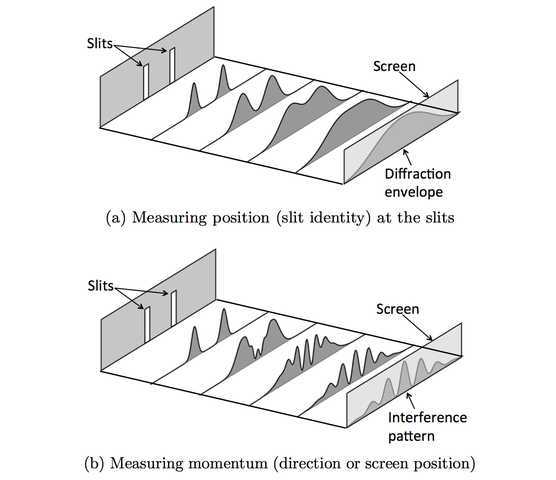

If a light detector is used to measure which slit each photon passes through, the interference pattern (Figures 2d and 3b) is replaced by a broad diffraction envelope (Figure 3a). The diffraction envelope looks like the sum of two single-slit patterns, as if the light behaved like two noninterfering streams of particles.

Figure 3: The double-slit experiment can produce either (a) a broad diffraction pattern or (b) an interference pattern. Height indicates intensity. (a) If slit identity (photon position at the barrier) is measured, waves from the two slits do not interfere. (b) If slit identity is not measured, the waves produce an interference pattern as they travel away from the slits.

Crucially, a diffraction envelope is observed when waves from different slits are prevented from interfering—for example, by recording photons from each slit separately on a photographic plate (opening one slit at a time). The image captured is then the simple sum of photons from each slit: a diffraction envelope. This demonstrates that using a detector to find slit identity destroys the interference pattern.

Despite many ingenious experiments, any attempt to determine which slit each photon passed through forces the light to stop behaving like a wave and to behave instead like a stream of particles. The transition from wave-like to particle-like behavior is intimately related to Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle, which we explain below.

Matter Waves

If the light is replaced by a beam of electrons, an interference pattern is again observed, as if the electrons were waves (compare with Figure 2d). This was surprising: before 1927, electrons were thought to behave like tiny billiard balls. De Broglie proposed in 1923 that electrons could behave like waves, and more radically that all matter has wave-like properties—so-called matter waves.

Since then, double-slit experiments have demonstrated matter-wave interference with whole atoms and even with large molecules such as buckminsterfullerene (C60).

But I digress—let’s return to the main subject.

Did the Photon Pass Through One Slit or Two?

The puzzle is that a photon (or a molecule) cannot, as a particle, pass through both slits, so we ask: did the photon pass through only one slit, and if so, which one?

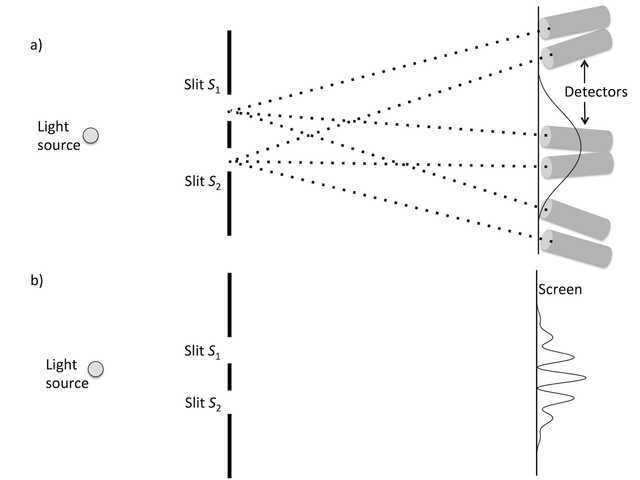

Consider replacing the screen with an array of long tubes, each pointing at a single slit and ending in a photodetector, as in Figure 4a. There should be a pair of detectors at each screen position, each member of the pair aimed at a different slit. Any detection at a tube points back to one slit only.

If we used this apparatus, the distribution of detected photons would be a diffraction envelope (as in Figures 3a and 4a). That envelope matches the pattern obtained when the slits are opened one at a time, confirming that measuring slit identity prevents interference.

Figure 4: An imaginary experiment for wave–particle duality. (a) If slit identity is measured using oriented detectors at the screen, momentum precision is reduced and a diffraction envelope is observed. (b) If slit identity is not measured, the screen measures direction (momentum) with high precision and an interference pattern appears. In Wheeler’s delayed-choice experiment, the choice of measurement is made after the photon has passed the slit(s).

Thus, detectors that measure slit identity force particle-like behavior. Leaving both slits open without such detectors restores the interference pattern: this is the essence of wave–particle duality.

Heisenberg’s Uncertainty Principle

Although counterintuitive, these results are consistent with Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle. When slit identity is not measured, the uncertainty in the particle’s screen position is roughly equal to the fringe spacing in the interference pattern (i.e., comparable to the width of each bright region in Figure 1).

More generally, any reduction in uncertainty about slit identity (position at the barrier) increases uncertainty in the momentum of the photons as they exit the slits. Since momentum includes direction, greater momentum uncertainty blurs the photon landing positions on the screen. This is the position–momentum trade-off: position indicates slit identity and momentum (direction) determines screen position.

In practice, it is possible to vary how much position information is obtained by changing detector accuracy. As more position (slit) information is gained, the interference fringes wash out and the pattern gradually becomes a broad diffraction envelope.

Heisenberg originally explained the principle by noting that shining light on an electron perturbs it, introducing uncertainties. More fundamentally, because position and momentum behave like waves, Fourier analysis implies an inequality—Heisenberg’s inequality—that makes precise the trade-off: reducing position uncertainty increases momentum uncertainty and vice versa, so both cannot be known exactly.

Wheeler’s Delayed-Choice Experiment

So far we have measured two aspects of each photon: its final position on the screen (which relates to momentum at the slit) or its slit identity (position at the barrier). If we decide in advance to measure screen position, it seems plausible to say the photon “went through both slits.” If we measure slit identity, it seems the photon “went through a single slit.”

Wheeler’s delayed-choice experiment asks what happens if we change the experimental setup while the photon is in transit between the slits and the screen. If our choice of measurement alters how each photon behaves, we might expect to decide before the photon reaches the slits. But what if the decision is made after the photon has passed the slit(s) but before it reaches the screen or tube detectors?

In such a setup, once the photon is in transit we randomly choose to either leave the screen in place (measuring screen positions and producing an interference pattern) or remove the screen (revealing tube detectors that measure slit identity and thus producing a diffraction envelope). Jacques et al. (2007) performed an experiment along these lines using interferometers. When the screen was left in place, an interference pattern was observed; when the screen was removed and detectors revealed, a diffraction-like distribution was observed.

Crucially, the choice about which measurement to perform was made (at random) after the photon had passed the slit(s). In effect, the observed behavior—whether the photon behaved like a wave (interference) or like a particle (diffraction)—appeared to depend on a decision made after the photon passed the slit(s).

To be precise: if the distance between the slits and the screen is S, then the photon transit time is T = S / c seconds, where c is the speed of light. Suppose a decision is made at time t and the photon arrives at the screen a short time dt later. If dt < T, the photon was in transit when the decision was made. By selecting only those photons for which dt < T, we can ensure the measurement choice was made while the photon was between slit and screen.

In principle, the slit–screen distance can be made extremely large so that photons take billions of years to arrive. Then a decision made now about which measurement to perform would seem to affect how the photons behaved billions of years ago. As we should expect, these results remain consistent with Heisenberg’s principle: measuring slit identity increases uncertainty in momentum and destroys interference, regardless of when the measurement choice is made.

Re-Writing Quantum History

Suppose we want to “rewrite” a small piece of history. How could we do it, and how far back could the edit reach?

As we have seen, a decision made now about whether to leave the screen in place effectively determines how photons behaved in the past. If we remove the screen (revealing detectors), the results ensure photons are recorded as having exited a single slit. If we leave the screen in place, photons produce an interference pattern, consistent with having sampled both slits. Either decision can be made after the photons have passed the slit(s).

The temporal reach of the effect depends on the photons’ transit time. Natural phenomena such as gravitational lensing can mimic distant “slits,” making it possible, in principle, for temporal editing to reach back extremely far—up to the age of the universe in extreme scenarios.

Finally, not everyone agrees that Wheeler’s delayed-choice experiment literally edits the past. Like most quantum-mechanical equations, the formalism admits multiple physical interpretations. To appreciate the ambiguity, one must study the governing equations of quantum mechanics and the many interpretive frameworks that physicists use.

James V. Stone is an Honorary Associate Professor at the University of Sheffield, UK.

References

V. Jacques, et al. Experimental realization of Wheeler’s delayed-choice gedanken experiment. Science, 315(5814):966–968, 2007.

Note: This is an edited extract from The Quantum Menagerie by James V. Stone (published December 2020). Chapter 1, the table of contents, and book reviews can be seen here.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!