VHE Gamma Rays from Sgr A*: Black Holes and CTA Observations

Table of Contents

Black Hole Key Points

- Black holes (BHs) have a gravitational pull so strong that nothing, not even light, can escape.

- BHs can be divided into two main classes: stellar-mass black holes and supermassive black holes (SMBHs).

- BHs are observed indirectly through the accretion flow they emit, the supersonic, collimated jets they produce, and their gravitational influence on surrounding objects.

- Very high energy (VHE) emission refers to gamma rays with energies above 100 giga‑electron volts (GeV).

- Black holes advect magnetic fields via the accreting matter that falls into them.

- Gamma rays can be produced by highly energetic protons and neutrons known as cosmic rays (CRs).

- CR acceleration may be caused by magnetic reconnection, which happens when oppositely directed magnetic field lines approach, reconnect, and release magnetic energy to accelerate particles.

- The mean free path (λ) of interactions gives the typical distance a particle travels before interacting with components of the medium.

Black holes are fascinating because of their extreme gravity and still poorly understood properties. They are not empty voids; they are astronomical objects with gravity so strong that nothing, not even light, can escape. The “surface” of a black hole, the event horizon (EH), defines the boundary where the escape velocity for any particle exceeds the speed of light. Matter and radiation can fall past the event horizon but cannot return.

Black holes can be divided into two main classes. Stellar-mass black holes form when a star with more than ~20 solar masses reaches the end of its life. Supermassive black holes (SMBHs) are believed to reside in the nuclei of galaxies; their origin is still not well understood. The SMBH at the center of the Milky Way is Sagittarius A* (Sgr A*) — see Sgr A*.

Once formed, black holes can grow by accreting surrounding matter, including gas from neighboring stars and by merging with other black holes. How are BHs observed? Indirectly: via the accretion flow they produce and the radiation that flow emits, via collimated jets, and via their gravitational influence on nearby objects.

Observations and instruments

The central region of the Milky Way has been observed in the VHE regime by imaging atmospheric Cherenkov telescopes (IACTs) for over a decade. In the electromagnetic spectrum, VHE emission refers to gamma rays with energies above 100 GeV.

After years of IACT observations, astronomers have measured VHE radiation coming from the central ~10 pc (1 pc = 3.26 light-years) of our galaxy. This region includes the location of Sgr A*. However, the angular resolution of current Cherenkov telescopes is insufficient to pinpoint the exact origin of the VHE emission. Key questions remain: Is Sgr A* accelerating the particles that produce the observed VHE radiation? If so, what acceleration mechanism operates there?

What is this radiation?

Electromagnetic radiation propagates as waves or photons across a broad range of frequencies, from radio waves at low frequencies to gamma rays at the highest frequencies (MeV and above).

Gamma rays can be produced when highly energetic protons and nuclei (cosmic rays, CRs) interact with ambient gas, magnetic fields, or radiation fields. The exact site and mechanism of CR production around Sgr A* are uncertain. One plausible mechanism is magnetic reconnection, where oppositely directed magnetic field lines approach, reconnect, and convert magnetic energy into particle kinetic energy.

Do black holes have magnetic fields? Yes — magnetic fields are advected by the accreting plasma, and charged particles follow field lines during reconnection and acceleration.

How do we study this radiation?

Simulation setup

To test whether Sgr A* can produce the observed gamma rays, scientists run numerical simulations of the accretion flow around the SMBH and estimate the resulting gamma-ray emission. Assuming magnetic reconnection accelerates particles, CR protons are injected in reconnection regions in the simulations.

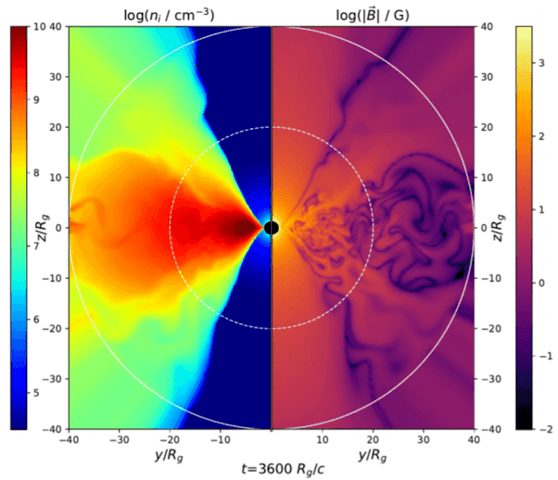

Figure 1 shows a snapshot of the simulated accretion flow: a map of gas density and magnetic field intensity around the SMBH at a given instant.

Figure 1: Density (left) and magnetic field map (right) of the simulation.

In the models, CRs are assumed to be produced in the inner region (inside the dashed white circle). The resulting gamma-ray radiation is then tallied at an outer spherical shell represented by the continuous white line.

Particle interactions, cascading, and mean free path

Accelerated CRs that escape the inner region interact with surrounding gas and fields, producing gamma rays, electrons, and neutrinos. Gamma-ray absorption by low-energy photons of the medium produces electron–positron pairs; those electrons can further boost photons to gamma energies via inverse Compton (IC) scattering.

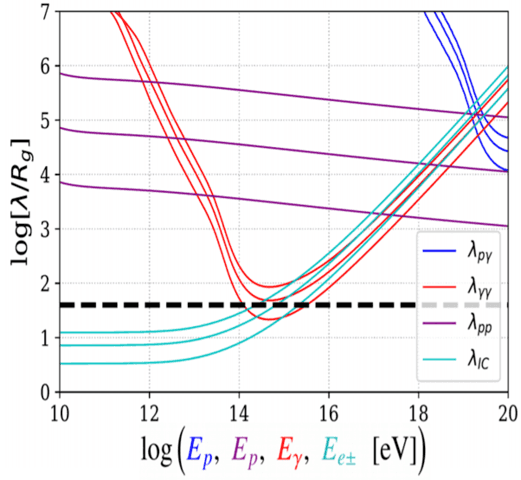

These secondary particles and photons interact further, producing particle cascades whose efficiency depends on the amount and distribution of target material. The likelihood of interactions is characterized by the mean free path (λ), the typical distance a particle travels before interacting (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: Mean free path of the interactions.

The indices in the figure indicate different interactions: “gamma” is CR–radiation interactions, “gamma-gamma” is photon–background radiation interactions, “pp” is CR–thermal particle (proton–proton) interactions, and “IC” is inverse Compton scattering of electrons with photons.

The results

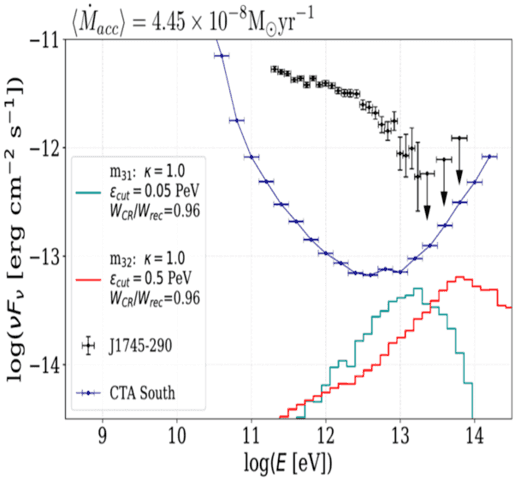

With the simulated environment and injected CRs accelerated by magnetic reconnection, researchers calculate the high-energy gamma-ray emission that escapes the system and would be detected at Earth. Figure 3 shows a set of model fluxes for a chosen BH accretion rate. The model curves (green, purple, red) are compared with observed flux points (black) reported by the H.E.S.S. telescopes. Note that the H.E.S.S. data correspond to an extended region of ~10 pc around the Galactic Center, so the exact source of the emission cannot be uniquely identified from current data.

Figure 3: The calculated flux (photons per unit time per unit area) vs. energy for Sgr A*, compared with observed flux (black symbols).

The green curve matches the observed VHE points better but is likely unphysical because the implied electron population would overproduce quiescent X-ray synchrotron emission from the Galactic Center. The purple and red models do not exceed X-ray constraints and require a much smaller fraction of the available magnetic reconnection power (WCR); however, they contribute less to the currently observed VHE flux and remain consistent with existing H.E.S.S. upper limits.

Future observations with the Cherenkov Telescope Array (CTA), with improved angular resolution and sensitivity (blue sensitivity curve in Figure 3), will be able to test the purple and red emission models. CTA should detect any source radiating above its sensitivity curve and can localize the emission more precisely.

The scientific team concludes that magnetic reconnection in the accretion flow of Sgr A* can produce VHE gamma rays observable with CTA if the accretion rate onto the SMBH exceeds 10^-7 M⊙ per year. Thus, CTA observations will provide valuable insight into cosmic-ray acceleration and high-energy processes at the heart of the Milky Way.

References

Alves Batista, R.; de Gouveia Dal Pino, E. M.; Carlos Rodríguez-Ramírez, J. (Instituto de Astronomia, Geofísica e Ciências Atmosféricas (IAG-USP), Universidade de São Paulo)

A Nuclear Fusion Physicist and Astrophysicist.

BSc Physics & Engineering, MSc Nuclear Physics & Engineering, MSc Astrophysics, PhD Plasma Physics

Well, I’m not so sure about that. While I don’t think MOND has anything to do with gravity (purely my opinion), I think it does tell us something about galaxy formation – not sure what, but something – and that something should be understood. If MOND is telling us something about galaxies, it would explain why it works so well on galactic scales – and nowhere else.

There are other empirical laws, like Tully-Fisher (and Baryonic Tullly-Fisher), and by invoking them one appears wise. For some reason, considering MOND in the same category is considered crazy. Even though BTFR is a prediction of MOND, i.e. the same observed fact can be described in two ways mathematically. Loving Tully-Fisher but hating MOND (as an empirical fact, not as a theory of gravity) is not really a consistent position, but it seems lots of people hold it.

Now onto LSB galaxies. In my best Indiana Jones “snakes” voice, “Why did it have to be LSB galaxies?” They are dim – it’s in the name after all – and because they are dim they are hard to see and harder to measure. When you do see one and measure it well, it is likely brighter than average, because otherwise it wouldn’t have ended up in your sample. These are among the hardest of measurements to do well, and the thing you would most like in the case of difficult measurements – high statistics – isn’t here yet. Rather than pointing at individual outlier galaxies, it would be much, much better to have a distribution of them. We’re not there yet.

You should also be careful what you ask for with “DM-free galaxies”. How did they get this way? Presumably, they had gravitational interactions with other galaxies that did this, but universality of free fall makes it hard to do. It is especially hard to do without disrupting the baryonic matter in the galaxy. Then again, maybe it’s bias: a lot of disruption blows the galaxy apart making it even lower surface brightness, so we don’t see it. Maybe a little disruption increases star formation so it’s easier to see. Again, we don’t know how dark matter stripping is supposed to work, so we don’t really know if these galaxies look like they are supposed to after a dark-matter-ectomy.

Very interesting. I find the “DM-free galaxies” so interesting, because it seems to rule out MOND-like theories of gravity, but of course one has to wait for better evidence to draw that conclusion.

There is a relationship between central black hole mass and the galactic bulge. M33 has no bulge to speak of and no CBH to speak of. There are similarly “thin” galaxies with CBH’s, so I think the relationship between these galaxies and their central black holes remains unclear.

The dark-matter less galaxies are still somewhat controversial. The DF2 and DF4 examples are problematic in the same way. There is an interesting paper by Mancera-Pina et al. which purports to have discovered six more. However, the error bars are large, and LSB galaxies suffer from selection biases. I think the “without dark matter” conclusion may be a bit premature – yes, half of the galaxies are on the “zero dark matter” line, but data also fall above and below this line. I’d like to see more data before forming any conclusion.

Intetersting! So a super-massive black hole is not necessary to form a galaxy. There seems to be nothing what doesn’t occur somewhere in the universe. Another fascinating thing is that astronomers find more and more dwarf galaxies without dark matter too.

”

Are there galaxies which have no black hole in their center?

”

M33 appears not to have one.

”

Did it start out that way? Seems I would have noticed. The orginal post was VERY long, yes like an article but I didn’t think it was posted like an article the way it obviously is now.

”

You’re right, it was migrated into Insights.

”

Something went wrong with the SMBH label. It stands for supermassive black hole (the type you find in galaxy centers), not stellar mass black hole.

[USER=310841]@phinds[/USER]: It’s an insights article.

”

Did it start out that way? Seems I would have noticed. The orginal post was VERY long, yes like an article but I didn’t think it was posted like an article the way it obviously is now.

That’s a great article (is there no way to give 5 stars to it anymore?).

That brings me to a (maybe stupid) question. Are there galaxies which have no black hole in their center? If not, are there galaxies forming because of the presence of a black hole or the other way around (kind of egg-hen problem)?

Something went wrong with the SMBH label. It stands for supermassive black hole (the type you find in galaxy centers), not stellar mass black hole.

[USER=310841]@phinds[/USER]: It’s an insights article.