Astrophotography: Mounts, Tracking & Image Processing

Table of Contents

Series links

- Part 1: Introduction to Astrophotography

- Part 2: Intermediate Astrophotography

- Part 3: Advanced Astrophotography

Motivation

“I’ve tried astrophotography and want to know how to improve.”

Choosing a mount

Here’s where I assume you are contemplating the purchase of a tracking mount — a motorized tripod. Far from being an afterthought, “A mount must relate to the telescope tube like a clockwork to the hand on the clock.” Purchasing a tracking mount represents a significant investment of time and money, with time being the more important—although you get what you pay for.

Before you buy, ask yourself: do you have time to spend a night outside at least twice a week for a year to learn the mount? How much time do you want to spend setting up and packing up each night? Can you set up in your backyard, or must you drive somewhere? Mounts are electrically powered, so you will need either a battery or a power cord. Autoguiders require a computer, which increases complexity. Finally, mounts are very heavy and don’t lend themselves well to travel.

Types of motorized mounts

There are two basic types of motorized tracking mounts: alt-azimuth (Dobsonian) and equatorial. Equatorial mounts hold the camera steady in equatorial coordinates; Dobsonian mounts hold the camera steady in horizon coordinates.

One disadvantage of Dobsonian mounts is that the camera must roll about the optical axis as the mount tracks; if it cannot, you will see field rotation — the starfield slowly rotates in the field of view. One disadvantage of equatorial mounts is susceptibility to vibration. I use an equatorial mount.

Exposure time and tracking

One important transition when moving to a motorized mount is that the maximum acceptable shutter time is no longer binary. With a static tripod you have a simple cutoff: exposures shorter than a given time are almost always sharp; longer exposures are almost always blurred. With a tracking mount, tracking errors introduce variability.

There will be an optimal maximum shutter time where, for example, ~50% of your images are acceptable. This optimal time can be 10–30× what you can achieve on a static tripod, but if that still isn’t enough for very faint objects, you must improve your mount’s tracking accuracy.

Tracking accuracy

Inaccuracies with an equatorial mount primarily stem from two sources: imperfect polar alignment and periodic error of the motor drive.

Polar alignment error

Polar alignment error is the misalignment between the RA rotation axis of an equatorial mount and the Earth’s rotation axis. In the northern hemisphere Polaris is currently ~0.75° offset from the rotation axis (slightly more than one lunar diameter), so an equatorial mount cannot be precisely aimed at Polaris. In the southern hemisphere there is no bright pole star, so alignment methods differ.

Polar alignment should be as accurate as possible — tenths of a degree or better. My mount settles during the first 30 minutes or so; I periodically re-check and correct the polar alignment during the night.

Polar alignment solutions

- Solution 1: polar alignment scope — most equatorial mounts include a slot for an illuminated polar alignment scope with a reticle for fine pointing; it’s worth the extra expense.

- Solution 2: declination drift alignment — a classic method to fine-tune polar alignment (I haven’t personally used it): http://www.skyandtelescope.com/astronomy-resources/accurate-polar-alignment/

Periodic error correction

Equatorial mounts convert a relatively fast motor rotation into a very slow rotation for the camera using gears. Manufacturing tolerances cause non-uniform motion: sometimes the camera moves too fast, sometimes too slow. This effect repeats every full gear revolution — hence, “periodic error.”

Periodic error produces star trails aligned exactly in the east–west (RA) direction. If your residual streaks are curved or not aligned with RA, then polar alignment is insufficient.

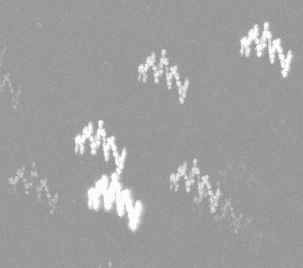

Here’s an example of the effect: 50 consecutive 10‑second exposures taken at 800/5.6 (400/2.8 + 2× tele). Periodic error is shown up–down in the example, while declination drift is left–right. One exposure (the last) may be especially bad, but most exposures show relative motion between the sensor and starfield. You can also see imperfect polar alignment.

Guiding as solution

Solution: guiding. Manual guiding is tedious; automatic guiding uses a guide camera and computer (more gear). Guiding can eliminate up to ~80% of periodic error if your mount can learn its corrections. After a round of manual guiding, I get:

Solution: guiding. Manual guiding is tedious; automatic guiding uses a guide camera and computer (more gear). Guiding can eliminate up to ~80% of periodic error if your mount can learn its corrections. After a round of manual guiding, I get:

In my example the polar alignment is still off, but periodic error is about 50% lower, and image acceptance increased from ~20% to ~40%.

Field rotation

Field rotation affects horizon-coordinate mounts (Dobsonians): the starfield appears to rotate at ~15 arcsec/sec about the optical axis. Long exposures will show rotation-dependent star trails. Field de-rotators — rotating prisms or similar devices — can correct this motion. I have limited experience with field rotation and do not know the full effect when a Dobsonian is not level.

Magnitudes, detectors, and photon flux

Magnitude-to-flux formula

Apparent magnitudes are logarithmic; irradiance from two objects (I1, I2) relates to magnitudes (m1, m2) by:

I1/I2 = 2.512^(m2 – m1). Each increment in magnitude is −1.3 Ev.

Representative fluxes

Digital sensors have (nearly) linear sensitivity to irradiance. Converting apparent magnitude to irradiance requires the object’s spectrum; a practical approach uses V-band magnitudes and Jansky units. The following table summarizes representative objects and their fluxes.

| Object | Apparent magnitude | Jy | photons s⁻¹ m⁻² | irradiance [W/m²] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sun | -26.74 | 1.81E+14 | 4.37E+20 | 1.30E+03 |

| Full moon | -12.74 | 4.54E+08 | 1.10E+15 | 3.27E-03 |

| Crescent moon | -6 | 9.14E+05 | 2.21E+12 | 6.58E-06 |

| Vega | 0 | 3.64E+03 | 8.79E+09 | 2.62E-08 |

| Stars in Big Dipper | 2 | 5.77E+02 | 1.39E+09 | 4.15E-09 |

| Eye limit (small cities) | 3 | 2.30E+02 | 5.55E+08 | 1.65E-09 |

| Eye limit (dark skies) | 6 | 1.45E+01 | 3.50E+07 | 1.04E-10 |

| — | 12 | 5.77E-02 | 1.39E+05 | 4.15E-13 |

| — | 15 | 3.64E-03 | 8.79E+03 | 2.62E-14 |

| — | 19 | 9.14E-05 | 2.21E+02 | 6.58E-16 |

Imaging implications

Astrophotography greatly amplifies dynamic range challenges. Extended objects like nebulae and galaxies are reported with apparent magnitudes computed as if all light fell on a single pixel — the opposite of imaging — so those magnitudes can be misleading for imaging work.

Sensor example and practical limits

Sensor specifications

We can use a camera as a radiometric detector and compare expected photon counts to measured values. (Sensor specs source: http://www.sensorgen.info/.)

My sensor: quantum efficiency 47%. At ISO 500, read noise ≈ 3.7 e⁻, full-well ≈ 10,329 e⁻, dynamic range ≈ 11.5 Ev. Note: because of read noise the camera can reliably distinguish only ~2,800 charge increments — consistent with ~11.5 Ev effective dynamic range.

Measured example

To recap a measured example: a single 400/2.8, 15‑second ISO 500 image produced an average grey-level background of 3,500, and a magnitude 14.1 star produced a grey-level of 4,542 (1,242 levels above background). These per-pixel values correspond to ~2,200 e⁻ and ~2,860 e⁻ respectively.

Background and detection limits

Compare that to expectations from photon flux tables: a 14.1 magnitude star alone would generate ~550 e⁻/pixel — much lower than the measured grey levels. The missing component is background illumination.

Light-polluted (moonless) night sky luminance is roughly 0.1 mcd/m². Converting that (assuming typical urban spectral content) and calculating the angular field per pixel gives ~3.4×10⁻¹⁴ J/pixel for a 15‑second exposure through my lens — equivalent to about a magnitude 10.8 star. Accounting for PSF spreading (point vs. diffuse source) changes the background-equivalent to approximately magnitude 12.1. That makes the ~570 e⁻ excess from a magnitude 14.1 star only slightly above background, consistent with measurements.

This highlights how sensitive modern commercial cameras are: you can detect femtojoule-level energies that previously required professional observatories.

Lower magnitude (fainter) detection depends on total exposure and ability to separate stars from background. If each 15‑second frame needs ~4 excess e⁻/pixel (just above read noise), that corresponds to ~magnitude 19 in a single frame. Over a 2‑hour total exposure, a magnitude 16 star contributes ~760 excess e⁻/pixel — and with stacking you may pull out ~magnitude 18.5. Improving tracking to permit longer individual exposures (30–60 s) improves detection limits accordingly.

Extended, low-surface-brightness objects are harder to judge because of how apparent magnitude is defined. Occultation detection remains a reasonable target for amateur equipment (see example paper): http://iris.lam.fr/wp-content/uploads/2013/08/1305.3647v1.pdf

Tone mapping and dynamic range

Mapping methods

Monitors typically display ≤8 bits per channel. To reproducibly post-process high-dynamic-range images you must operate on quantitative metrics (histograms, gamma curves) rather than purely by eye.

Logarithmic tone mapping compresses a wide dynamic range (e.g., ~10 stellar magnitudes) into an 8‑bit display. Adjusting gamma changes contrast. In practice, mapping functions more complex than log (for example, log(log(D)) or cube-root mappings) can improve faint-nebula contrast — but remember, more compression tends to increase apparent FWHM of stars.

Special note: there is a useful alternative magnitude scale for faint objects, the ‘asinh’ magnitude scale: https://arxiv.org/abs/astro-ph/9903081

Color balancing

Practical white-balance steps

Consistent color balance is best done ‘by instrument’ rather than ‘by eye.’ Because tone maps are nonlinear, you should set at least three white-balance setpoints: black, white, and a mid-tone neutral grey. Without a mid-tone anchor you can get hue shifts in midtones even when black and white are neutral.

Channel-by-channel gamma correction can help; automated programs that access astrometry databases can also assist with photometric calibration (example): http://bf-astro.com/excalibrator/excalibrator.htm

Deconvolution and sharpening

Unsharp masking workflow

When the imaging system is approximately linear and shift-invariant, the image equals the object convolved with the PSF. Deconvolution attempts to invert that process to recover detail. Numerical issues (zeros in the PSF) make this nontrivial; deconvolution helps but rarely performs miracles.

Unsharp masking is a simple and effective sharpening method: duplicate the image, blur the duplicate with a kernel (try 5–10 pixels), scale the blurred layer (e.g., ×0.3) and subtract it from the original. This reduces low-frequency content and boosts edge contrast.

CLAHE (local contrast)

Contrast-limited adaptive histogram equalization (CLAHE) boosts local contrast by equalizing many small, local histograms. It amplifies small intensity variations and works well on starfields, but can introduce artifacts in dense clusters or extended objects.

More: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Adaptive_histogram_equalization#Contrast_Limited_AHE

Background subtraction and flats

Using flats

Fast lenses often show vignetting (fall-off) as the entrance pupil effective area varies with angle. Use flat frames — uniformly illuminated images (e.g., a white LCD screen) — to correct fall-off. Flats can reduce background variation by up to ~95% when done carefully; you may need slight gamma adjustments on the flat reference for optimal results.

Large-scale background removal

When the sky background varies on large spatial scales compared to stars, local averaging or subtracting a heavily blurred version of the image (kernel ~50–100 pixels) will remove >99% of background. For very large-scale variations (approaching the whole image), blur with a very large kernel (≈1000 pixels) and subtract; add a border near the image median first to avoid edge artifacts.

Noise reduction and color-space tricks

HSB noise reduction trick

Noise appears as high-frequency intensity fluctuations. A mild Gaussian blur (≈0.6 pixel sigma) often suffices, but specialized denoising tools can do better.

A useful trick: convert the RGB stack to HSB (Hue, Saturation, Brightness). Per-channel noise is roughly equally distributed in RGB; in HSB you can smooth H and S aggressively (neighboring pixels should have similar hue and saturation) while preserving B. Reducing H and S noise eliminates a large fraction of perceived color noise; convert back to RGB afterward for improved results.

Extras: spectrophotography and panoramas

Spectrophotography

Astrospectrophotography: with 10+ s exposures you can place an inexpensive transmission diffraction grating in the optical path (for example at the filter slot) and measure spectral differences between planets or bright stars.

Panoramas

Stitched panoramas: expand your field of view by stitching frames. Keep color balance and SNR consistent across frames — processing ‘by instrument’ rather than ‘by eye’ helps maintain uniformity.

Related posts

Missed the first two parts?

PhD Physics – Associate Professor

Department of Physics, Cleveland State University

На этом сайте собрана актуальная и ценная информация по разным темам.

Гости могут открыть ответы на важные вопросы.

Материалы обновляются часто, чтобы вы каждый могли изучать новую аналитику.

Простая навигация сайта помогает быстро отыскать нужные разделы.

tattoobrend.com

Разнообразие тем делает ресурс универсальным для всех читателей.

Любой сможет выбрать советы, которые интересуют именно ему.

Присутствие практических рекомендаций делает сайт особенно значимым.

Таким образом, данный сайт — это надёжный источник актуальной информации для широкого круга пользователей.

Подбор доктора-остеопата — важный этап на пути к улучшению самочувствия.

Для начала стоит понять свои потребности и ожидания от консультации у остеопата.

Необходимо оценить квалификацию и практику выбранного остеопата.

Комментарии обратившихся помогут сделать обоснованный решение.

https://forum.storeland.ru/index.php?/user/40899-maslowgenrix/

Также нужно учитывать техники, которыми оперирует доктор.

Начальная консультация даёт возможность понять, насколько комфортно вам общение и подход специалиста.

Не забудьте сравнить тарифы и условия работы (например, очно).

Грамотный выбор специалиста поможет улучшить процесс восстановления.

[QUOTE="Andy Resnick, post: 5594921, member: 20368"]Andy Resnick submitted a new PF Insights postAdvanced Astrophotography Continue reading the Original PF Insights Post.“Outstanding collection of information, I'll be rereading this many times. :thumbup: Thanks again.

Continue reading the Original PF Insights Post.“Outstanding collection of information, I'll be rereading this many times. :thumbup: Thanks again.

Great guide series Andy, thanks!