Es vs Em Fields in Electrodynamics: Capacitor & Antenna

Table of Contents

Abstract

The analysis of the two kinds of electric fields, namely the irrotational and non-conservative, is extended to electrodynamics, as exemplified by the high-frequency behavior of a parallel-plate capacitor and a radiating antenna.

Since the concept of split electric fields still seems unfamiliar in some quarters, I will start back at square one by quoting Resnick & Halliday (p. 883, 1966 edition):

“The induced electric fields that are set up by the induction process are not associated with charges but with a changing magnetic flux. Although both kinds of electric fields exert forces on charges, there is a difference between them. The simplest (but not the only) manifestation of this difference is that lines of E associated with a changing magnetic flux (Em) can form closed loops; lines of E associated with charges (Es) cannot but can always be drawn to start on a positive charge and end on a negative charge.”

We now extend the concept of split E fields from static (Refs. 1–3 incl.) to dynamic conditions with two examples.

1. Increasing the frequency of the displacement current ## \partial \bf D/\partial t ## in a capacitor

E fields in a parallel-plate capacitor

Feynman (Notes, Vol. II, Ch. 23, sect. 23.2; Ref. 4) provides a clear analysis of split electric-field generation as the frequency of the applied voltage varies in a round parallel-plate capacitor.

Starting at DC or very low frequencies, we get the familiar Es field with field lines starting and ending on the plate charges. This is Feynman’s E1 field (or ## \Gamma_1 ## in fig. 23-4).

Evolution of the Em field

As frequency increases, a significant B field begins to form. This B field follows Maxwell’s equation ## \nabla \times \bf H = \partial \bf D/ \partial t ##. The H field pervades the region between the plates, forming concentric circular layers stacked from the top plate to the bottom plate.

The changing B field generates a secondary E field which Feynman calls E2 (## \Gamma_2 ##). E2 is emf-generated and non-conservative, i.e., an Em field. E2 is zero at radius r = 0 and at the top and bottom plates; it builds up with radius roughly as ## r^2 ##, orthogonal to the plates and parallel to the E1 flux lines (edge effects are ignored as usual).

Vector addition of Es and Em

The two fields E1 and E2 (Es and Em) add vectorially to give the inverted-parabolic field shown in Feynman’s fig. 23-5 and expressed in eq. 23-8. Feynman extends the analysis to show an infinite series of fields E3, E4, … (all B-dot generated, hence Em fields). E1 and E2 suffice to demonstrate the generation of split E fields under dynamic conditions.

2. A radiating antenna

Radiating-antenna field determination

The magnetic field at distance r from a short (## d \ll \lambda ##) dipole antenna is obtained by computing the magnetic retarded potential ## \bf A ##. From ## \bf A ## one finds the magnetic-field components and then the E-field components. The last step is done either by using the remaining Maxwell equation or by imposing the Lorentz gauge ## \nabla \cdot \bf A = -\mu \epsilon~\partial V/\partial t ## (cf. Ref. 5). That reduces the E-field expression to an equation in terms of ## \bf A ## alone. I will not repeat these standard derivations here; they are in the usual textbooks.

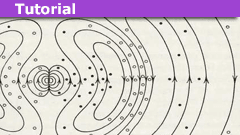

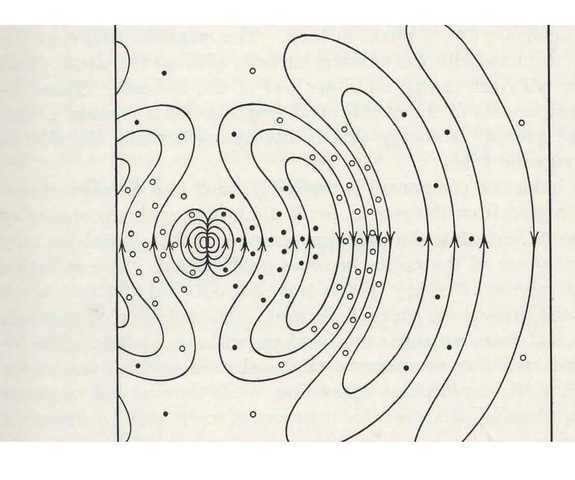

Figure 1 — Electric and Magnetic Fields Near a Radiating Short Dipole Antenna

From Es to Em

Figure 1 (Ref. 5) shows how the Em field is generated from the Es field. The electric wave begins as a predominantly Es field close to the antenna, indicated by flux lines between charges attached to the antenna. From the beginning, that Es field produces an H field (indicated by dots for into/out of the page). This H field, via Maxwell’s equation ## \nabla \times \bf H = \partial \bf D/\partial t ##, generates the closed-loop Em field. As the field radiates away from the antenna, the Es contribution diminishes while the Em contribution becomes dominant. For r > 1 wavelength the wave is essentially wholly Em and no longer coupled to antenna charges.

The E field in spherical coordinates

In spherical coordinates (## r, \theta, \phi ##), with ## 0 < \theta < \pi ## and ## 0 < \phi < 2\pi ##, the dipole antenna extends along the polar axis. The combined field ## \bf E = \bf E_s + \bf E_m ## has r and ## \theta ## components (## E_r ## and ## E_{\theta} ##); the ## \phi ## component is zero.

The antenna induction (near) field

In the near (induction) field, ## E_r ## and ## E_{\theta} ## fall off as ## 1/r^3 ##. The electric field of a quasi-stationary oscillating dipole at frequency ## \omega ## can be written as

## \bf E_s = (1/4\pi) (1/r^3) [(3 \bf p \cdot \hat {\bf r})~\hat {\bf r} – \bf p]e^{j \omega t} ##

where ## \bf p ## is the dipole moment. One resolves ## \bf E_s ## into spherical r and ## \theta ## components and compares these with the fields computed from the potentials above.

Es field amplitude and behavior

The comparison shows the same ## 1/r^3 ## roll-off for the quasi-stationary dipole and for the antenna’s induction field. Thus, the field near the antenna behaves predominantly as an Es field, especially as ## r \to 0 ##.

The antenna radiation (far) field

In the far (radiation) field, the surviving E component is ## E_{\theta} ##, which falls off as ## 1/(\lambda r) ##. At large distances the E field is essentially entirely Em. (The idea of electrons “flying through the air” is picturesque but strictly metaphoric: no charges, no Es field.)

There is an intermediate zone where ## E_r ## and ## E_{\theta} ## coexist and the dominant decay is roughly ## 1/r^2 ##. At the distance where ## \lambda/r = 2\pi ## the Es and Em amplitudes are comparable.

Visualization of the evolving radiation pattern

Figure 1 gives a clear visual of fields at near, intermediate, and long distances from the antenna. Very near the antenna the field is nearly all Es, but an H field appears immediately via ## \nabla \times \bf H = \epsilon_0 \partial \bf E_s/\partial t ##. Further out, that H field produces an Em contribution (via ## \nabla \times \bf H = \epsilon_0 \partial \bf E_m/\partial t ##). Thus Es transitions into a mixed Es+Em field and ultimately into a nearly pure Em field that propagates away in closed loops, effectively independent of the antenna charges at large r.

Em and Es at a receiving antenna

At the receiving antenna, the incoming Em wave induces an Es field within the antenna conductors; that induced Es generates a measurable voltage V given by

## V = \int \bf E_s \cdot \bf dl ##

Final observations on Es and Em fields

One may ask: why emphasize two kinds of electric fields when many experimental results can be explained without that distinction? Consider these points:

- It can reveal charge distributions that might otherwise be overlooked. Discovering charges and their associated fields is fundamental.

- It can prevent incorrect claims such as “Kirchhoff was wrong” when the distinction between Es and Em was not taken into account.

- It clarifies that the statement “voltage is the line integral of the electric field” applies only to irrotational (Es) fields unless explicitly qualified.

- It helps identify faulty reasoning even in otherwise authoritative sources (I can provide at least one example by PM if desired).

- As physicists, we should seek deep understanding beyond explaining limited test results produced by inadequate procedures or apparatus (see point 1 above).

Summary

The two kinds of electric field, previously analyzed in electrostatic and quasi-static contexts in other Insight blogs, occur in dynamic conditions as well. Awareness of this duality often provides important information about the sources and behavior of electric fields in many applications.

References:

1. https://www.physicsforums.com/insights/a-new-interpretation-of-dr-walter-lewins-paradox/

2. https://www.physicsforums.com/insights/introduction-to-electric-vector-potential-and-its-applications/ (including appended references)

3. https://www.feynmanlectures.caltech.edu/II_23.html

4. H. H. Skilling, Fundamentals of Electric Waves, 2nd ed., John Wiley & Sons.

5. https://farside.ph.utexas.edu/teaching/em/lectures/node45.html

AB Engineering and Applied Physics

MSEE

Aerospace electronics career

Used to hike; classical music, esp. contemporary; Agatha Christie mysteries.

Понятие гедонизма — это направление в философии, которое выдвигает наслаждение в центр человеческой жизни.

Согласно этому взгляду, поиск радости считается важным мотивом существования.

Этот подход не всегда подразумевает отсутствие ограничений.

Во многих трактовках он предполагает баланс и ответственное отношение.

https://www.tumblr.com/sneakerizer/803905934927740928/c%C3%A9line-%D0%BB%D0%B0%D0%BA%D0%BE%D0%BD%D0%B8%D1%87%D0%BD%D0%B0%D1%8F-%D1%80%D0%BE%D1%81%D0%BA%D0%BE%D1%88%D1%8C-%D0%B8-%D1%82%D0%B8%D1%85%D0%B0%D1%8F-%D0%B4%D0%B5%D1%80%D0%B7%D0%BE%D1%81%D1%82%D1%8C

Сегодняшнее восприятие этой идеи часто акцентирует внимание на качестве жизни.

При этом важную роль играет гармония между удовольствиями и ценностями.

Данный взгляд может способствовать личному развитию.

В итоге, гедонизм рассматривается как философская перспектива, а не как отказ от ответственности.